High-altitude regions are generally rich in solar energy resources, offering advantages such as long sunshine duration and vast land areas, which are conducive to the large-scale development of photovoltaic power generation. Currently, numerous large-scale photovoltaic power stations, such as those in Kela and Longyangxia, have been constructed in northwestern and southwestern high-altitude areas of China. These power stations predominantly use traditional silicon-based photovoltaic components, which exhibit low power generation efficiency. In contrast, tandem solar cells, particularly perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells, demonstrate higher conversion efficiency, enabling efficient power generation in high-altitude environments.

High-altitude areas are characterized by significant temperature variations and strong solar irradiation. When perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells operate under these conditions, substantial thermal stress is generated internally, raising concerns about long-term operational stability. Previous research has extensively investigated the thermal-mechanical properties of traditional solar cells in various scenarios. For instance, some studies developed thermal stress calculation models for thin-film solar cells under different regional and temperature conditions, revealing that the maximum thermal stress in cadmium telluride thin-film solar cells in areas with large temperature differences is approximately nine times that of conventional crystalline silicon solar cells. Other research employed simulation methods to study the opto-electro-thermal coupling behavior in microscale perovskite solar cells, indicating that electrode regions with poor heat dissipation are most prone to degradation and failure. Additionally, simulations replacing metal contacts with graphene in perovskite solar cells showed that graphene contacts enhance heat dissipation without compromising electrical output, thereby improving thermal stability. Furthermore, coupled opto-electro-thermal models for perovskite solar cells have been established to elucidate the microscopic energy conversion mechanisms and propose external cooling and internal material optimization strategies to reduce cell temperature. However, existing simulation studies primarily focus on defect analysis in materials and comparative cell performance, with limited attention to the thermal-mechanical analysis of perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells in high-altitude environments.

This study investigates the thermal-mechanical characteristics of perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells in high-altitude areas. We first develop a simulation model for analyzing the thermal-mechanical behavior of these cells under high-altitude conditions and validate the model’s reliability through experimental tests. Subsequently, we analyze the effects of different regional conditions on cell temperature, thermal stress, and thermal deformation, and explore the instantaneous thermal-mechanical behavior of the cells throughout the day in realistic outdoor scenarios. The findings provide valuable insights for the large-scale engineering application of perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells in high-altitude regions.

Research Methodology

Simulation Design and Cell Modeling

The study focuses on perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells, with a perovskite cell as the top layer and a silicon cell as the bottom layer. Based on the typical dimensions of mainstream laboratory-scale perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells, we construct a geometric model with a length and width of 10 mm × 10 mm. The cell structure comprises multiple layers, including a glass cover, ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA), indium tin oxide (ITO), tin oxide (SnO₂), fullerene (C₆₀), perovskite, Spiro-OMeTAD, silicon, and a glass substrate. The silicon layer, cover, and substrate are relatively thick, while the other layers are very thin. To simplify calculations, the thickness of the top cover and substrate is set to 10 μm. The internal layers are assumed to be bonded. For meshing, considering computational accuracy and deformation characteristics, the edge regions of the cell are locally refined. After grid independence verification, the total number of grids is set to 303,116. Heat transfer between the cell and the environment is modeled as convective and radiative heat transfer, with reasonable simplifications applied to the boundary conditions using COMSOL software.

Determination of Model Input Conditions

The input conditions for the simulation model are set based on actual scenarios, as summarized in Table 1.

| Model Region | Input Conditions |

|---|---|

| Cell Upper Surface | Convective heat transfer, radiative heat transfer |

| Cell Lower Surface | Convective heat transfer |

| Perovskite Layer | Internal heat source |

| Silicon Layer | Internal heat source |

| Cell Side Surface | Adiabatic |

The cell’s upper surface is exposed to the environment, while the lower surface is attached to an insulating layer. Both surfaces are under typical wind-cooling conditions, with a wind speed of 2 m/s assumed for base cases; the impact of varying wind speeds is later evaluated experimentally. Radiative heat exchange on the upper surface is calculated as surface-to-environment radiation. The side surfaces, contributing minimally to heat dissipation (approximately 5%), are treated as adiabatic. During operation, the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell absorbs sunlight, converting light energy into electrical and thermal energy, accompanied by optical losses. The perovskite and silicon layers are set as internal heat sources in the thermal calculations.

The direct irradiance power on the photovoltaic cell surface is calculated as:

$$ P_d = G A_{\text{cell}} $$

where \( P_d \) is the direct irradiance power (W), \( G \) is the solar irradiance intensity (W/m²), and \( A_{\text{cell}} \) is the surface area of the solar cell (m²).

The output electrical power and thermal power of the tandem solar cell are given by:

$$ P_{c,e} = P_d \eta_{sc} $$

$$ P_{c,th} = P_d (1 – \eta_{sc}) $$

where \( P_{c,e} \) is the output electrical power (W), \( P_{c,th} \) is the output thermal power (W), and \( \eta_{sc} \) is the photoelectric conversion efficiency of the tandem solar cell (%).

Considering the constraints imposed by surrounding encapsulation in practical applications, the bottom surface of the cell substrate is set as a fixed constraint.

Material Properties

The thermophysical properties of the materials used in the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell are sourced from literature and software databases, as listed in Table 2.

| Parameter | Glass | ITO | Perovskite | Spiro-OMeTAD | Silicon |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (kg/m³) | 2203 | 7120 | 4000 | 4128 | 2329 |

| Thermal Conductivity (W/(m·K)) | 1.38 | 10.0 | 0.50 | 0.49 | 130.0 |

| Specific Heat Capacity (J/(kg·K)) | 703 | 370 | 258 | 262 | 677 |

| Thermal Expansion Coefficient (10⁻⁶ K⁻¹) | 0.55 | 0.55 | 36.40 | 6.40 | 2.49 |

| Young’s Modulus (GPa) | 73.1 | 76.4 | 12.8 | 12.8 | 112.0 |

| Poisson’s Ratio | 0.17 | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

Experimental Testing and Model Validation

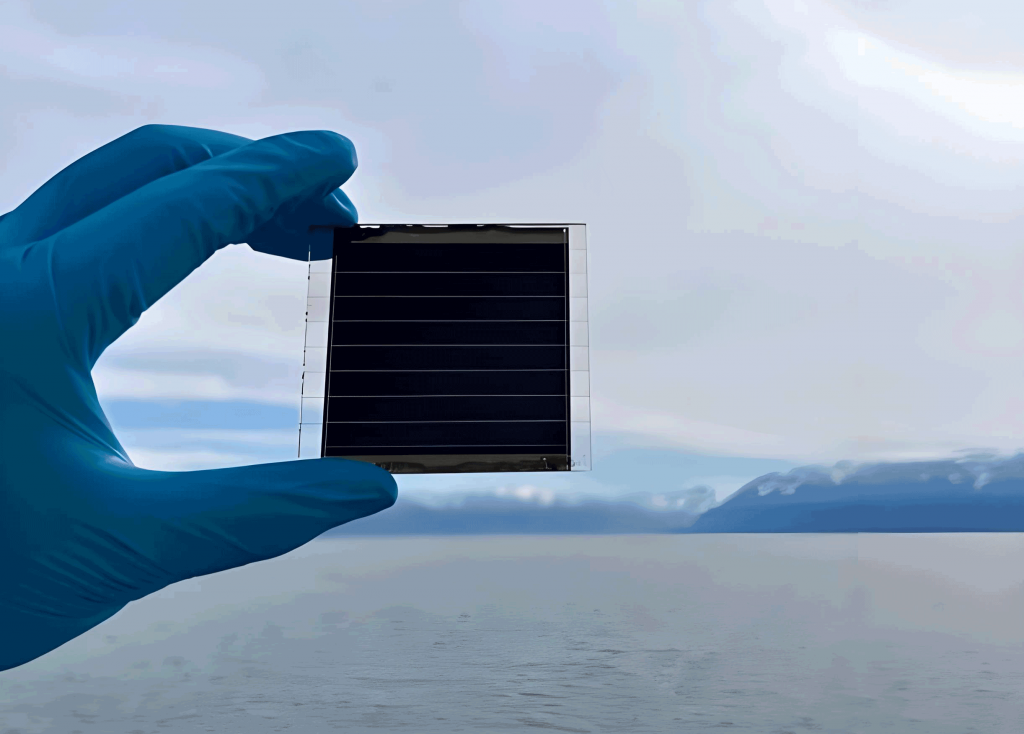

We established an experimental test system to evaluate the reliability of the simulation model and analyze the impact of cooling conditions on the thermal-mechanical characteristics of the tandem solar cell. A perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell was fabricated, and a photovoltaic device performance test platform was set up. The thermal-mechanical performance of the component was tested under summer conditions in a high-altitude area and at different wind speeds. Experiments were conducted indoors using a simulated light source to irradiate the cell, with environmental humidity controlled by a humidifier and wind speed adjusted by a fan. An electronic load measured the open-circuit voltage, operating voltage, operating current, and output power of the solar cell, while an infrared thermal imager (FLIR T540) captured temperature distribution data on the cell surface. Based on data from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts, the irradiance of the simulated light source was set to 896 W/m², and the ambient temperature was maintained at 22°C during testing.

Experimental and simulation data are presented in Table 3.

| Wind Speed (m/s) | Maximum Cell Temperature (°C) | Average Cell Temperature (°C) | Cell Efficiency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 31.9 | 30.6 | 19.555 |

| 2 | 31.2 | 29.8 | 19.676 |

| 4 | 30.8 | 29.2 | 19.745 |

| 6 | 30.6 | 28.7 | 19.789 |

| 8 | 30.5 | 28.3 | 19.821 |

| 10 | 30.5 | 28.0 | 19.846 |

As wind speed increases from 1 m/s to 10 m/s, the maximum cell temperature decreases from 31.9°C to 30.5°C, the average temperature decreases from 30.6°C to 28.0°C, and efficiency increases from 19.555% to 19.846%. This trend indicates that higher wind speeds enhance cooling, reducing cell temperature and improving efficiency. To assess the accuracy of our thermal-mechanical simulation model for perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells, we compared the calculated thermal stress with experimental data from literature on perovskite solar cells. The literature reported a maximum thermal stress of 54 MPa, while our simulation model yielded a maximum thermal stress of 60.6 MPa, resulting in a relative error of 12.2%. Furthermore, under typical summer conditions in a high-altitude area with a wind speed of 2 m/s, the differences between simulated and experimental average and maximum cell temperatures were 0.41°C and 0.32°C, with relative deviations of 1.4% and 1.0%, respectively. These results confirm the reliability of the simulation model.

Numerical Calculation Results and Analysis

Based on the simulation model, we analyze the temperature, thermal stress, and thermal deformation characteristics of the solar cell in different high-altitude areas, and examine the transient thermal-mechanical behavior during all-day operation.

Environmental Parameters in High-Altitude Areas

We selected five typical high-altitude regions in China—Kela, Longyangxia, Maoergai, Xiaowan, and Yebatan—for investigating the thermal-mechanical characteristics of perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells. These regions exhibit typical high-altitude environmental features, including strong irradiation and large diurnal temperature variations, making the results representative. Environmental data affecting the thermal-mechanical properties of the solar cell over the past year were processed for these regions, as summarized in Table 4.

| Region | Season | Minimum Ambient Temperature (°C) | Maximum Ambient Temperature (°C) | Maximum Irradiance (W/m²) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kela | Spring | -21.3 | 21.2 | 1003.8 |

| Summer | -3.5 | 21.8 | 896.1 | |

| Autumn | -17.0 | 18.5 | 1094.6 | |

| Winter | -23.2 | 11.4 | 1049.4 | |

| Longyangxia | Spring | -11.5 | 25.5 | 1048.7 |

| Summer | 6.4 | 29.1 | 897.9 | |

| Autumn | -10.3 | 24.5 | 1063.5 | |

| Winter | -22.5 | 12.5 | 1033.0 | |

| Maoergai | Spring | -22.3 | 19.5 | 1028.4 |

| Summer | 1.8 | 20.5 | 876.3 | |

| Autumn | -11.9 | 18.5 | 1083.6 | |

| Winter | -33.8 | 8.0 | 1021.5 | |

| Xiaowan | Spring | 6.8 | 32.9 | 915.2 |

| Summer | 15.3 | 32.3 | 838.2 | |

| Autumn | 5.4 | 29.2 | 905.5 | |

| Winter | 1.4 | 24.2 | 924.9 | |

| Yebatan | Spring | -23.1 | 19.0 | 1019.4 |

| Summer | 0.8 | 20.0 | 890.9 | |

| Autumn | -15.8 | 17.8 | 1014.7 | |

| Winter | -25.7 | 10.5 | 1072.3 |

Impact of Cell Packaging on Thermal-Mechanical Characteristics

Our simulation model includes glass encapsulation on both the top and bottom. While keeping other conditions constant, we varied the thickness of the glass cover and substrate to examine the effect of packaging on the thermal-mechanical characteristics of the perovskite solar cell. The results are summarized in Table 5.

| Thickness (μm) | Maximum Temperature (°C) | Maximum Thermal Stress (MPa) | Maximum Thermal Deformation (10⁻⁷ m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 40.1 | 18.5 | 3.8 |

| 100 | 40.1 | 19.2 | 3.5 |

| 200 | 40.1 | 19.8 | 3.2 |

| 400 | 40.1 | 20.5 | 2.9 |

| 600 | 40.1 | 21.1 | 2.6 |

| 800 | 40.1 | 21.8 | 2.3 |

| 1000 | 40.1 | 22.4 | 2.0 |

As the thickness of the glass cover and substrate increases from 10 μm to 1000 μm, the cell temperature remains virtually unchanged. However, the maximum thermal stress inside the cell increases slightly, and the maximum thermal deformation decreases gradually. This indicates that thicker packaging constrains the thermal deformation of the cell to some extent.

Temperature Characteristics of Solar Cells in Different Regions

By applying the environmental parameters of the five regions to the simulation model, we obtained the temperatures of the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell during daytime and nighttime, as shown in Table 6.

| Region | Daytime Temperature (°C) | Nighttime Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| Kela | 30.3 | -21.0 |

| Longyangxia | 29.5 | -10.5 |

| Maoergai | 20.2 | -34.0 |

| Xiaowan | 51.0 | 6.5 |

| Yebatan | 19.8 | -24.0 |

The cell reaches a maximum temperature of 51°C when operating in Xiaowan and a minimum temperature of -34°C in Maoergai. In Maoergai, the temperature fluctuation range of the photovoltaic cell can reach 76°C, highlighting the extreme conditions in high-altitude areas.

Thermal Stress and Thermal Deformation of Solar Cells in Different Regions

The thermal stress and thermal deformation of the tandem solar cell during daytime and nighttime are presented in Table 7, with deformation values taken as absolute values.

| Region | Condition | Maximum Thermal Stress (MPa) | Maximum Thermal Deformation (10⁻⁷ m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kela | Daytime (Expansion) | 22 | 4.50 |

| Nighttime (Contraction) | 35 | 6.80 | |

| Longyangxia | Daytime (Expansion) | 21 | 4.30 |

| Nighttime (Contraction) | 28 | 5.90 | |

| Maoergai | Daytime (Expansion) | 15 | 3.20 |

| Nighttime (Contraction) | 47 | 8.54 | |

| Xiaowan | Daytime (Expansion) | 29 | 5.80 |

| Nighttime (Contraction) | 10 | 2.10 | |

| Yebatan | Daytime (Expansion) | 18 | 3.70 |

| Nighttime (Contraction) | 32 | 6.20 |

During daytime operation, the cell expands due to heating, generating tensile stress. Under the highest temperature conditions in Xiaowan, the maximum thermal stress and thermal deformation are 29 MPa and 5.80×10⁻⁷ m, respectively. At night, the cell contracts due to cooling, generating compressive stress. Under the lowest temperature conditions in Maoergai, the maximum thermal stress and thermal deformation are 47 MPa and 8.54×10⁻⁷ m, respectively. The maximum thermal stress in the perovskite layer under the same environmental conditions is 14.9 times that in the silicon layer.

We simulated the stress distribution within the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell under extreme environmental parameters in the five regions. The results show that the stress is concentrated at the edges and corners of the cell, with maximum values occurring at the sharp corners. The interior of the cell exhibits relatively uniform stress distribution. Due to the much lower thermal expansion coefficient of the glass substrate compared to the perovskite and silicon layers, the substrate undergoes minimal deformation under extreme conditions. However, the perovskite and silicon layers expand or contract, interacting with the surrounding EVA, leading to squeezing or pulling at the edges. This causes thermal fatigue at the cell edges, making them susceptible to damage or fracture in practical applications.

Instantaneous Temperature Characteristics of Solar Cells

Under typical summer conditions in Xiaowan and winter conditions in Maoergai, we analyzed the impact of diurnal variations on the all-day instantaneous temperature characteristics of the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell. The temperature distribution within the cell is nearly uniform due to its thinness. The instantaneous temperature variation curves are shown in Figure 1.

The temperature variation can be modeled using the following equation for transient heat transfer:

$$ \rho c_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + q $$

where \( \rho \) is density, \( c_p \) is specific heat capacity, \( T \) is temperature, \( t \) is time, \( k \) is thermal conductivity, and \( q \) is heat generation rate.

In summer, the cell’s maximum and minimum temperatures are 46°C and 18°C, respectively, with the peak around 12:00 and the trough around 06:00. In winter, the maximum and minimum temperatures are 14°C and -33°C, respectively, following a similar pattern with extremes around 12:00 and 06:00.

Instantaneous Characteristics of Thermal Stress and Thermal Deformation

The instantaneous thermal stress variation of the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell under typical summer conditions in Xiaowan and winter conditions in Maoergai is illustrated in Figure 2.

The thermal stress \( \sigma \) can be related to temperature change \( \Delta T \) by:

$$ \sigma = E \alpha \Delta T $$

where \( E \) is Young’s modulus and \( \alpha \) is the coefficient of thermal expansion.

In summer, the cell experiences lower stress at night, gradually increasing with sunrise and reaching a maximum at noon. The maximum stress in the perovskite layer is 24 MPa, with fluctuations 13.3 times greater than those in the silicon layer. In winter, the cell exhibits higher stress at night, gradually decreasing with sunrise to a minimum at noon. The maximum stress in the perovskite layer is 47 MPa, with fluctuations 17.2 times greater than those in the silicon layer.

The instantaneous deformation characteristics of the cell under typical summer and winter conditions are shown in Figure 3. The internal materials expand or contract with temperature changes, with maximum deformation occurring at the four corners of the cell. In practice, due to constraints from the surrounding structure, the corners experience significant squeezing or pulling, easily leading to damage. In summer, around 12:00, when temperatures are highest, the cell undergoes the most pronounced expansion stress and deformation, with a local maximum deformation of 4.86×10⁻⁷ m. In winter, around 06:00, when temperatures are lowest, the cell experiences contraction stress and the greatest degree of shrinkage, with a corresponding local maximum deformation of 8.48×10⁻⁷ m.

Conclusion

In this study, we employed a multi-field coupled simulation approach to develop a thermal-mechanical calculation model for perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells in high-altitude areas. We quantitatively analyzed the cell temperature, thermal deformation, and thermal stress characteristics under typical high-altitude environmental conditions. The main conclusions are as follows.

First, in the performance test of the perovskite/silicon tandem solar cell component, the cell efficiency was 19.776%, with differences between simulated and experimental average and maximum temperatures of 0.41°C and 0.32°C, respectively. The relative deviations of the calculation model were 1.4% and 1.0%, confirming the model’s reliability.

Second, under high-altitude conditions, the cell can face a maximum temperature of 51°C and a minimum temperature of -34°C, with a maximum temperature fluctuation of 76°C.

Third, during operation in high-altitude areas, under typical summer conditions in Xiaowan, the maximum thermal stress and thermal deformation occur around 12:00, with values of 24 MPa and 4.86×10⁻⁷ m, respectively. Under typical winter conditions in Maoergai, the maximum thermal stress and thermal deformation occur around 06:00, with values of 47 MPa and 8.48×10⁻⁷ m, respectively.

Through simulation calculations, we obtained the thermal stress distribution of the cell operating in high-altitude environments, quantitatively revealing specific areas within the cell prone to stress concentration and damage. These findings provide a reference for optimizing the design of perovskite solar cells for long-term stable operation in high-altitude regions.