In modern power grids, the integration of renewable energy sources has necessitated the development of efficient and reliable energy storage solutions. Among these, the battery energy storage system plays a pivotal role in stabilizing grid operations, providing backup power, and enhancing energy management. However, large-scale battery energy storage systems, often configured in containerized setups, comprise hundreds to thousands of battery cells connected in series and parallel. The performance of such systems is heavily influenced by the consistency among individual cells. Due to the “barrel effect,” where the weakest cell dictates overall system capacity, any faulty cell can lead to significant capacity degradation, reduced efficiency, and even safety hazards like thermal runaway. Therefore, rapid and accurate identification of faulty cells within a battery energy storage system is crucial for maintaining system reliability and longevity. This study focuses on investigating the dynamic voltage characteristics of lithium iron phosphate (LiFePO₄) battery clusters during full charge-discharge cycles and pulse charge-discharge processes. By analyzing voltage variations, we propose a method for quickly detecting and locating faulty cells, thereby improving the maintenance and safety of battery energy storage systems.

The inconsistency in battery cells arises from variations in material properties, manufacturing processes, and operational conditions. In a battery energy storage system, these inconsistencies amplify at the module, cluster, and system levels, leading to uneven voltage distribution, accelerated aging, and potential failures. Traditional approaches, such as passive or active balancing techniques, mitigate inconsistencies at small scales but often fall short in large-scale applications. For instance, balancing circuits may not effectively address faults in a massive battery energy storage system with numerous cells, highlighting the need for alternative diagnostic methods. This research aims to bridge this gap by exploring voltage behavior under different operational modes, with an emphasis on pulse charge-discharge as a rapid diagnostic tool. Throughout this paper, we will repeatedly emphasize the importance of the battery energy storage system in ensuring grid stability and how our findings contribute to its optimization.

To understand the voltage dynamics, we first consider the fundamental model of a battery cell. The terminal voltage \(V\) of a cell during charge or discharge can be expressed as:

$$V = OCV(SOC) + I \cdot R_{int} + V_{polarization}$$

where \(OCV(SOC)\) is the open-circuit voltage as a function of state of charge (SOC), \(I\) is the current (positive for discharge, negative for charge), \(R_{int}\) is the internal resistance, and \(V_{polarization}\) represents polarization effects. In a battery energy storage system, cells are connected in series and parallel, leading to complex interactions. For a series-connected string, the total voltage \(V_{total}\) is the sum of individual cell voltages, while for parallel connections, currents may distribute unevenly due to differences in internal resistance. The inconsistency can be quantified by the voltage divergence \(\Delta V\) among cells:

$$\Delta V = \max(V_i) – \min(V_i) \quad \text{for} \ i = 1, 2, \dots, n$$

where \(n\) is the number of cells. A large \(\Delta V\) indicates significant inconsistency, often pointing to faulty cells. In this study, we monitor \(\Delta V\) under various conditions to identify anomalies.

The experimental setup involves a LiFePO₄ battery cluster designed for power storage applications. The cluster consists of 432 cells arranged in modules. Each module is configured as 2 parallel strings of 12 series cells, resulting in a nominal voltage of 38.4 V and a capacity of 310 Ah. Eighteen such modules are connected in series to form the battery cluster, with a total nominal voltage of 691.2 V, capacity of 310 Ah, and power rating of 107 kW. To introduce a fault scenario, one cell within the cluster is intentionally designed with a voltage短板 (i.e., lower capacity or higher internal resistance). Voltage data is collected from 216 points across the cluster using a battery management system (BMS), enabling detailed analysis.

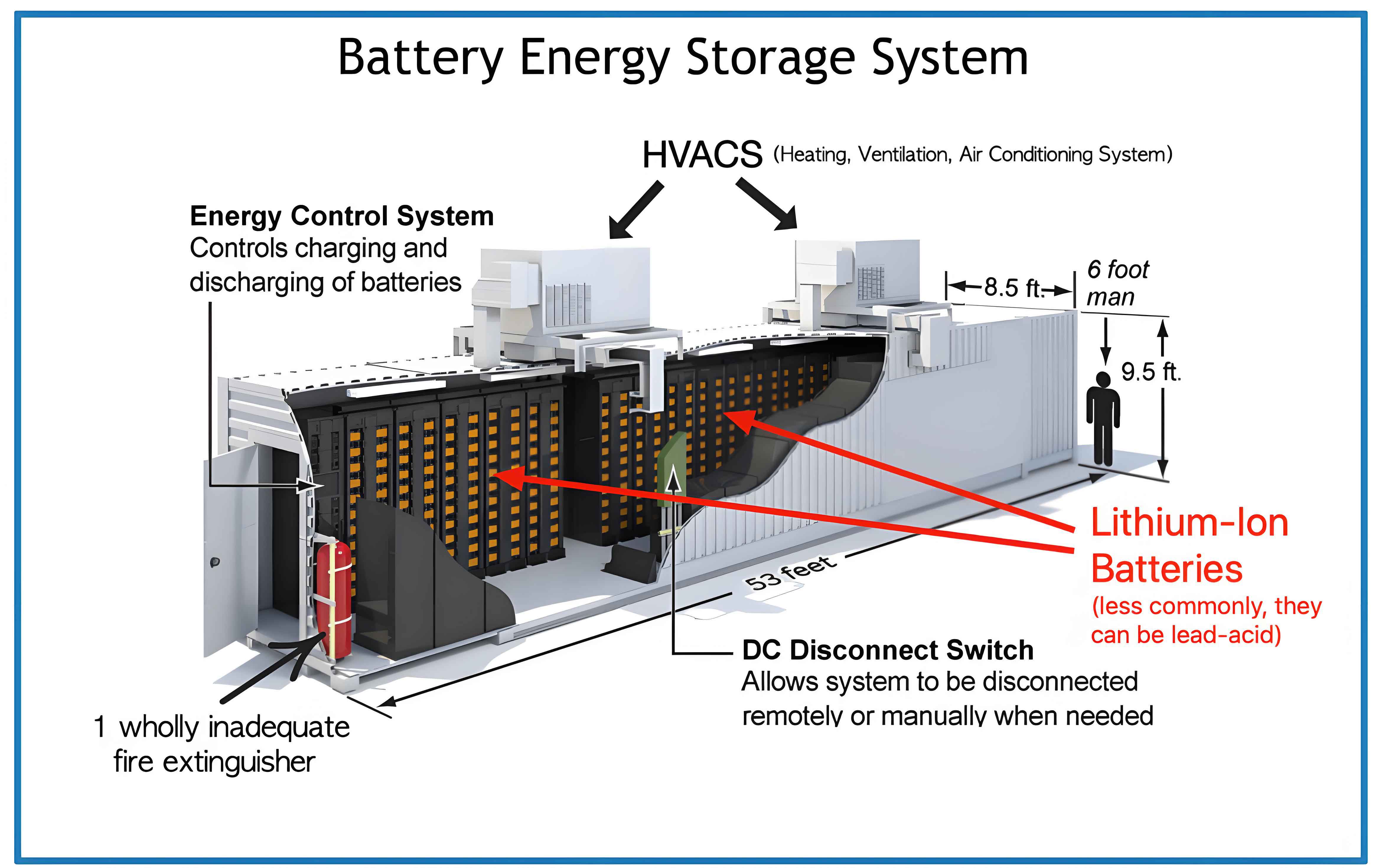

The testing platform, as illustrated above, includes a charge-discharge tester (PSC900-300), a 24 V power supply, protection units, control units, and voltage sensors. The main circuit facilitates charge and discharge operations, while the control loop manages data acquisition. This setup allows for precise control over charge-discharge profiles, including full cycles and pulse sequences. For the battery energy storage system, such testing is essential to evaluate performance under realistic conditions.

We conducted two primary tests: full charge-discharge cycles and pulse charge-discharge sequences. The full charge-discharge test follows standard protocols, where the cluster is charged at rated power until any cell reaches 3.65 V or SOC hits 100%, and discharged until any cell hits 2.80 V or SOC reaches 0%. Voltage data is recorded at key points, such as at 50% SOC, charge end, and discharge end. The pulse test involves charging the cluster to 40% SOC, then applying pulse charge and discharge at powers of ±10 kW, ±20 kW, ±40 kW, and ±80 kW, with 60-second intervals between transitions. Voltage snapshots are taken during each pulse to capture dynamic responses. These methods are designed to stress the battery energy storage system and reveal inconsistencies that might otherwise remain hidden.

The results from the full charge-discharge test are summarized in Table 1, which shows the voltage distribution across cells at different SOC levels. At 50% SOC, the voltage range is narrow, indicating relatively uniform behavior. However, at the charge end, the voltage spread increases, and at the discharge end, it becomes pronounced, with the faulty cell (ID 158) exhibiting a significant voltage drop. This aligns with the barrel effect, where the weakest cell limits overall performance. The voltage difference \(\Delta V\) can be modeled as:

$$\Delta V_{end} = \Delta V_{base} + \Delta V_{fault} \cdot f(SOC)$$

where \(\Delta V_{base}\) is the baseline inconsistency, \(\Delta V_{fault}\) is the contribution from the faulty cell, and \(f(SOC)\) is a function that amplifies near SOC extremes. For a healthy battery energy storage system, \(\Delta V_{end}\) should remain small, but faults cause it to spike.

| SOC Condition | Maximum Cell Voltage (V) | Minimum Cell Voltage (V) | Voltage Difference \(\Delta V\) (V) | Fault Cell ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50% SOC | 3.38 | 3.36 | 0.02 | Not apparent |

| Charge End | 3.65 | 3.52 | 0.13 | 158 (slight indication) |

| Discharge End | 3.08 | 2.80 | 0.28 | 158 (clear indication) |

Figure 1 compares the voltage curves of the faulty cell (ID 158) and a normal cell (ID 160) during the full cycle. The curves overlap for most of the cycle, diverging only at the extremes. This suggests that full cycles are inefficient for fault detection, as they require extensive time and energy. In contrast, the pulse test provides rapid insights. Table 2 presents voltage data during pulse charge and discharge. As pulse power increases, the faulty cell’s voltage deviates more sharply, with \(\Delta V\) growing from 0.01 V at 10 kW to 0.06 V at 80 kW during charging, and from 0.02 V to 0.05 V during discharging. This behavior can be described by the dynamic voltage response:

$$V_{response}(t) = V_{steady} + \Delta V_{pulse} \cdot e^{-t/\tau}$$

where \(V_{steady}\) is the steady-state voltage, \(\Delta V_{pulse}\) is the pulse-induced deviation, and \(\tau\) is the time constant. For a faulty cell, \(\Delta V_{pulse}\) is larger due to higher internal resistance or lower capacity. Thus, the battery energy storage system can be quickly assessed by analyzing voltage responses to pulses.

| Pulse Power (kW) | Maximum Cell Voltage (V) | Minimum Cell Voltage (V) | Voltage Difference \(\Delta V\) (V) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +10 (Charge) | 3.35 | 3.34 | 0.01 | Fault cell ID 158 at minimum |

| -10 (Discharge) | 3.22 | 3.20 | 0.02 | Fault cell ID 158 at minimum |

| +20 (Charge) | 3.37 | 3.34 | 0.03 | Deviation increases |

| -20 (Discharge) | 3.22 | 3.19 | 0.03 | Deviation increases |

| +40 (Charge) | 3.38 | 3.35 | 0.03 | Consistent trend |

| -40 (Discharge) | 3.22 | 3.18 | 0.04 | Consistent trend |

| +80 (Charge) | 3.41 | 3.35 | 0.06 | Maximum deviation |

| -80 (Discharge) | 3.22 | 3.17 | 0.05 | Maximum deviation |

To further analyze the pulse response, we can derive a model for cell voltage under pulsed currents. Assuming a simplified equivalent circuit with an internal resistance \(R_{int}\) and a capacitance \(C\) representing polarization, the voltage drop \(\Delta V_{pulse}\) during a pulse of current \(I\) is:

$$\Delta V_{pulse} = I \cdot R_{int} + I \cdot \frac{1 – e^{-t_p/\tau}}{C}$$

where \(t_p\) is the pulse duration. For a faulty cell, \(R_{int}\) is typically higher, leading to a larger \(\Delta V_{pulse}\). This model explains why pulse tests are effective: they exaggerate differences that are subtle under steady-state conditions. In a battery energy storage system, implementing such pulses during routine maintenance can help identify faults early without draining the system.

The implications of these findings are significant for the design and operation of battery energy storage systems. First, the pulse method reduces diagnostic time from hours (for full cycles) to minutes, saving energy and minimizing downtime. Second, it enables real-time monitoring; by embedding pulse sequences into BMS algorithms, faults can be detected proactively. Third, it enhances safety by preventing over-discharge or overcharge of weak cells. We propose a fault identification algorithm based on pulse responses: if \(\Delta V\) exceeds a threshold \(\theta\) during a pulse, the system flags the lowest-voltage cell as faulty. The threshold can be adaptive, based on historical data from the battery energy storage system.

Moreover, the study highlights the importance of cell matching in battery energy storage systems. Inconsistencies can be mitigated through better manufacturing control, but post-deployment monitoring is equally vital. Our method complements balancing techniques by providing a diagnostic layer. For instance, in a large battery energy storage system, periodic pulse tests can guide balancing efforts, ensuring that resources are focused on problematic cells.

We also explored the effect of temperature on voltage characteristics, as it is a critical factor in battery energy storage system performance. Temperature variations can alter internal resistance and OCV, but our tests were conducted under controlled conditions (25°C). Future work could integrate thermal models to refine fault detection. Additionally, the pulse method can be extended to other battery chemistries, such as NMC or LTO, though the voltage thresholds would differ.

In conclusion, this research demonstrates that pulse charge-discharge is a rapid and efficient method for identifying faulty cells in a battery energy storage system. Compared to full cycles, pulses amplify voltage differences, allowing for quick localization of faults with minimal energy expenditure. The battery energy storage system benefits from improved reliability, safety, and lifespan. We recommend incorporating pulse-based diagnostics into BMS standards for large-scale energy storage. As renewable integration grows, robust management of battery energy storage systems will be key to grid stability, and our contribution provides a practical tool for achieving that goal.

For future directions, we plan to investigate multi-fault scenarios and develop machine learning algorithms to predict cell failures based on pulse data. The battery energy storage system is evolving, and advanced diagnostics will play a crucial role in its sustainability. By continuously monitoring voltage dynamics, we can ensure that these systems operate at peak efficiency, supporting the global transition to clean energy.