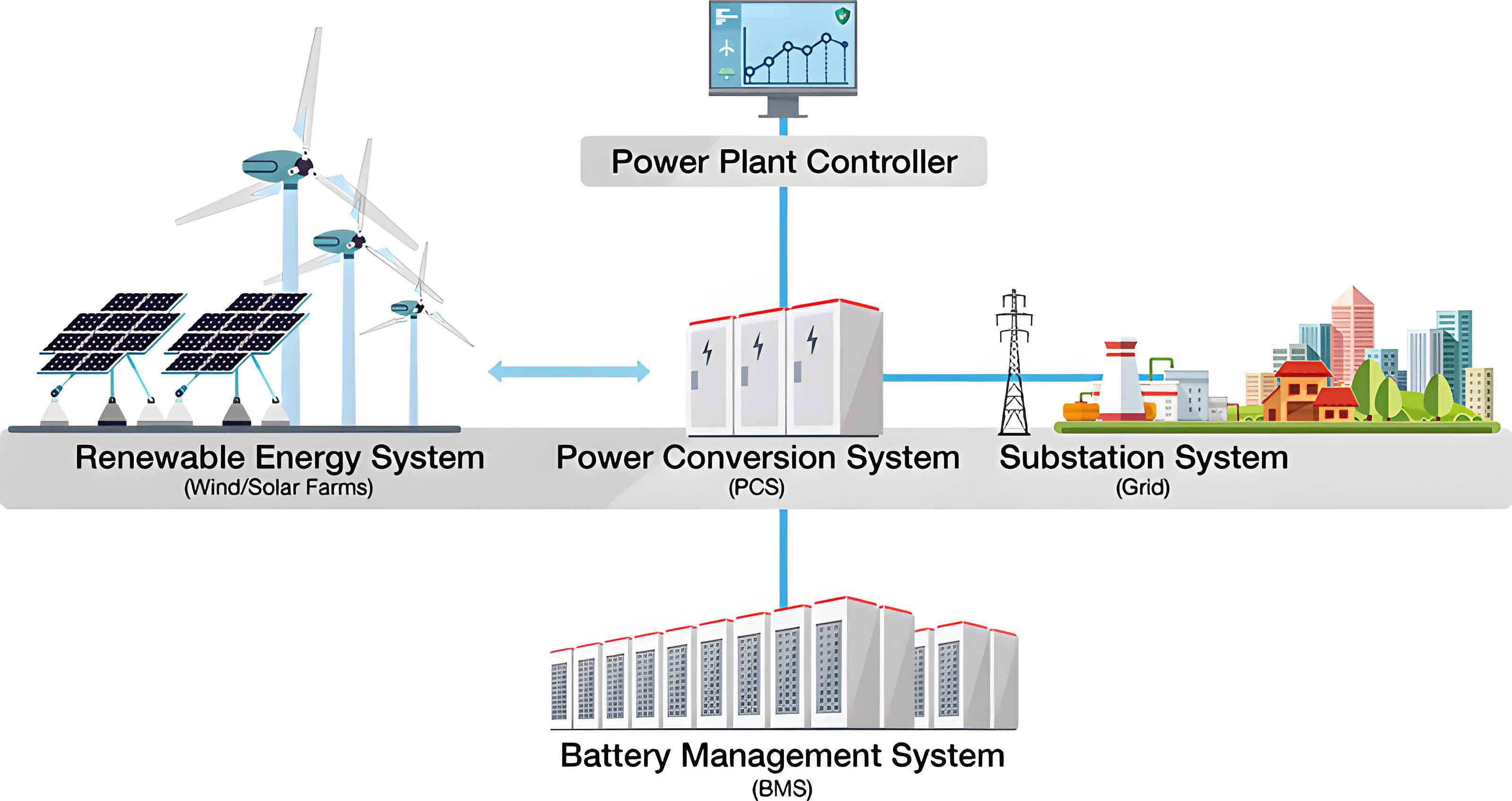

With the rapid advancement of new power systems, the scale of the energy storage market continues to expand. Among various technologies, electrochemical energy storage, particularly lithium iron phosphate battery-based systems, plays a crucial role in renewable energy integration and grid flexibility. Accurate state of charge (SOC) estimation for battery packs within a battery energy storage system is vital for safe operation, preventing overcharge or overdischarge, and extending battery life. However, under typical grid conditions such as peak shaving and frequency regulation, SOC estimation faces challenges due to complex operating environments, including high voltages, large currents, and battery pack inconsistencies. Traditional methods often fail to account for these dynamic conditions, leading to reduced estimation accuracy. In this article, we propose a novel SOC estimation model based on kernel principal component analysis (KPCA), pelican optimization algorithm (POA), and bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) to address these issues. Our approach leverages fused features from experimental data, optimizes model parameters, and validates performance under mixed conditions, aiming to enhance the reliability and precision of SOC estimation for battery energy storage systems.

The battery energy storage system is typically composed of multiple battery packs, each consisting of series-connected cells. The SOC of a battery pack, denoted as SOCpack, can be derived from individual cell SOCs. For a pack with N cells, the formula is given by:

$$ \text{SOC}_{\text{pack}} = \frac{Q_{\text{dis}}^{\text{pack}}}{Q_{\text{pack}}} = \frac{\min_{1 \leq k \leq N} (\text{SOC}_k C_k)}{\min_{1 \leq k \leq N} (\text{SOC}_k C_k) + \min_{1 \leq k \leq N} ((1 – \text{SOC}_k) C_k)} $$

where \( Q_{\text{dis}}^{\text{pack}} \) is the remaining discharge capacity, \( Q_{\text{pack}} \) is the current capacity, \( \text{SOC}_k \) is the SOC of the k-th cell, and \( C_k \) is the maximum available capacity of the k-th cell. Under peak shaving and frequency regulation, the charge-discharge patterns differ significantly. Peak shaving involves near-constant current operations, while frequency regulation requires frequent current adjustments based on grid frequency changes. To capture pack inconsistencies, we define voltage and temperature ranges as key indicators:

$$ \Delta U = U_{\text{max}} – U_{\text{min}} $$

$$ \Delta T = T_{\text{max}} – T_{\text{min}} $$

where \( U_{\text{max}} \) and \( T_{\text{max}} \) are the maximum voltage and temperature among cells, and \( U_{\text{min}} \) and \( T_{\text{min}} \) are the minimum values. These features, along with conventional parameters like pack voltage, current, and average temperature, form the basis for our SOC estimation model in a battery energy storage system.

In developing our SOC estimation framework, we first employ kernel principal component analysis (KPCA) for feature reduction. KPCA maps low-dimensional data to a high-dimensional space using kernel functions, preserving essential characteristics while eliminating redundancy. Given a dataset \( X = \{x_1, x_2, \dots, x_n\} \) with each sample \( x_j \) as a d-dimensional vector, the covariance matrix in the high-dimensional space \( F \) is computed as:

$$ C_F = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{j=1}^{n} \Phi(x_j) \Phi^T(x_j) $$

where \( \Phi(x) \) is a nonlinear mapping function. By solving the eigenvalue problem, we obtain principal components that capture the most significant variance. For the q-th principal component:

$$ T_q = v_q \Phi(x) = \sum_{j=1}^{n} \alpha_{q,j} K(x_j, x) $$

Here, \( T_q \) is the nonlinear principal component, \( v_q \) and \( \alpha_{q,j} \) are feature vectors, and \( K(x_j, x) \) is the kernel matrix. This process reduces the input dimensions from seven original features (e.g., pack voltage, current, voltage range, temperature range) to three principal components, which account for over 90% of the cumulative variance in both peak shaving and frequency regulation scenarios. This reduction enhances model efficiency and accuracy for the battery energy storage system.

Next, we utilize a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (BiGRU) network for SOC estimation. BiGRU combines forward and backward GRUs to capture both historical and future information in time-series data, making it suitable for long-sequence predictions. The GRU is a simplified variant of LSTM, offering faster convergence and computational efficiency. The BiGRU computation can be expressed as:

$$ \overrightarrow{c}_t = G(X_t, \overrightarrow{c}_{t-1}) $$

$$ \overleftarrow{c}_t = G(X_t, \overleftarrow{c}_{t-1}) $$

$$ h_t = \overrightarrow{w}_t \overrightarrow{c}_t + \overleftarrow{c}_t \overleftarrow{w}_t + b_t $$

where \( \overrightarrow{c}_t \) and \( \overleftarrow{c}_t \) are hidden states from forward and backward propagation, \( \overrightarrow{w}_t \) and \( \overleftarrow{w}_t \) are corresponding weights, \( b_t \) is the bias, and \( G(x) \) is the GRU function. To further optimize the BiGRU model, we integrate the pelican optimization algorithm (POA), a metaheuristic inspired by pelican hunting behavior. POA exhibits high convergence precision and search efficiency compared to traditional algorithms like particle swarm optimization. It involves two phases: exploration (global search) and exploitation (local search). The position update in the exploration phase is:

$$ x^{p1}_{ij} = \begin{cases} x_{ij} + \sigma (P_j – a x_{ij}), & F_P < F_i \\ x_{ij} + \sigma (x_{ij} – P_j), & F_P \geq F_i \end{cases} $$

where \( x^{p1}_{ij} \) is the updated position, \( \sigma \) is a random number between 0 and 1, \( P_j \) is the prey position, \( a \) is 1 or 2, \( F_P \) is the prey objective value, and \( F_i \) is the candidate solution objective value. In the exploitation phase, the update is:

$$ x^{p2}_{ij} = x_{ij} + R \left(1 – \frac{t_s}{T}\right) (2\beta – 1) x_{ij} $$

where \( R \) is a constant (0.2), \( t_s \) is the current iteration, \( T \) is the maximum iteration, and \( \beta \) is a random number between 0 and 1. POA optimizes BiGRU hyperparameters such as the number of hidden neurons, learning rate, and iteration count, improving SOC estimation performance for the battery energy storage system.

Our experimental setup simulates real-world operations of a battery energy storage system. We use a lithium iron phosphate battery pack with 8 series-connected cells, each with a nominal capacity of 220 Ah and voltage of 25.6 V. The test platform includes a battery testing system (BT60 V300 AC2), a thermal chamber (HCJB1000L-20) to maintain a constant 25°C environment, and an upper computer for data monitoring. We design charge-discharge strategies based on actual grid commands: for peak shaving, SOC varies from 10% to 90% to 10% with a steady current around 0.5 C (110 A), including short rest periods; for frequency regulation, SOC slowly decays from 90% to 10% with frequent shallow charge-discharge cycles at currents up to 0.5 C. Data sampling is performed at 15-second intervals, yielding 10,053 samples for frequency regulation and 2,078 for peak shaving after preprocessing. The features extracted include pack voltage, current, maximum/minimum cell voltages, voltage range, temperature range, and average pack temperature, which are then processed by KPCA.

| Working Condition | Sample Size | Principal Components | Cumulative Variance (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Shaving | 2,078 | 3 | 90.231 |

| Frequency Regulation | 10,053 | 3 | 92.900 |

The dataset is normalized and split into training, validation, and test sets in a 6:1:3 ratio. We incorporate historical SOC values as time-series features, using the past 10 time steps along with the current and past three principal components. Thus, the BiGRU input layer has 22 neurons, and the output is the estimated SOC at the current time step. POA is configured with a population size of 20 and maximum iterations of 50 to optimize the BiGRU parameters. We evaluate model performance using root mean square error (RMSE), mean absolute error (MAE), and coefficient of determination (R²), defined as:

$$ \text{RMSE} = \sqrt{\frac{1}{M} \sum_{i=1}^{M} (\text{SOC}_{M,i} – \text{SOC}_{P,i})^2} $$

$$ \text{MAE} = \frac{1}{M} \sum_{i=1}^{M} |\text{SOC}_{M,i} – \text{SOC}_{P,i}| $$

$$ R^2 = 1 – \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{M} (\text{SOC}_{M,i} – \text{SOC}_{P,i})^2}{\sum_{i=1}^{M} (\text{SOC}_{M,i} – \overline{\text{SOC}}_Q)^2} $$

where \( \text{SOC}_{M,i} \) is the measured SOC, \( \text{SOC}_{P,i} \) is the predicted SOC, \( \overline{\text{SOC}}_Q \) is the average measured SOC, and M is the total number of samples. Lower RMSE and MAE values indicate better accuracy, while R² closer to 1 reflects superior model fit.

To validate the effectiveness of KPCA, we compare SOC estimation results using original features versus reduced features. Under peak shaving conditions, the KPCA-POA-BiGRU model with reduced features achieves an RMSE of 0.008645, MAE of 0.008527, and R² of 0.9987, whereas using original features yields higher errors (RMSE: 0.033260, MAE: 0.022370, R²: 0.9406). Similarly, for frequency regulation, reduced features lead to RMSE of 0.009983, MAE of 0.010410, and R² of 0.9930, compared to RMSE of 0.061020, MAE of 0.047480, and R² of 0.7753 with original features. This demonstrates that feature reduction via KPCA not only improves estimation accuracy but also reduces model training time by 54.05 seconds for peak shaving and 138.7 seconds for frequency regulation, enhancing the efficiency of the battery energy storage system monitoring.

| Model | Peak Shaving RMSE | Peak Shaving MAE | Peak Shaving R² | Frequency Regulation RMSE | Frequency Regulation MAE | Frequency Regulation R² |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KPCA-POA-BiGRU | 0.008645 | 0.008527 | 0.9987 | 0.009983 | 0.010410 | 0.9930 | KELM | 0.024090 | 0.019680 | 0.9654 | 0.037650 | 0.022560 | 0.9532 |

| BiLSTM | 0.011050 | 0.012310 | 0.9892 | 0.015780 | 0.011020 | 0.9785 |

| BiGRU | 0.011360 | 0.012440 | 0.9875 | 0.016620 | 0.012330 | 0.9771 |

We further compare our KPCA-POA-BiGRU model with other machine learning approaches, including kernel extreme learning machine (KELM), BiLSTM, and standard BiGRU. As shown in the table, our model outperforms others in both peak shaving and frequency regulation scenarios. For peak shaving, KPCA-POA-BiGRU reduces RMSE by 23.9% and MAE by 31.46% compared to basic BiGRU, with R² improving by 1.14%. For frequency regulation, the improvements are even more pronounced due to the complex current patterns. This highlights the robustness of our optimized model in handling dynamic conditions within a battery energy storage system. Additionally, we test the model under mixed conditions that combine peak shaving and frequency regulation commands. By training separate models for each condition and switching based on grid instructions, we achieve an RMSE of 0.01097 and MAE of 0.009862, whereas a single model trained on mixed data yields higher errors (RMSE: 0.02872, MAE: 0.025460). This dual-model approach enhances stability and accuracy, making it suitable for real-time SOC estimation in diverse operational environments of a battery energy storage system.

The superior performance of our model can be attributed to several factors. First, KPCA effectively reduces feature dimensionality while preserving critical information related to SOC variations, such as pack inconsistencies and thermal effects. Second, BiGRU captures temporal dependencies in the data, leveraging both past and future contexts to improve prediction accuracy. Third, POA fine-tunes hyperparameters, ensuring optimal model configuration without manual trial-and-error. These elements collectively address the challenges posed by peak shaving and frequency regulation, where current fluctuations and pack heterogeneities can degrade SOC estimation. Moreover, the incorporation of voltage and temperature ranges as features directly accounts for cell imbalances, which are common in large-scale battery energy storage systems. Our experimental results confirm that these features contribute significantly to model accuracy, especially under frequency regulation where shallow cycles amplify inconsistencies.

From a practical perspective, accurate SOC estimation is essential for the safe and efficient operation of a battery energy storage system. It enables better energy management, prevents detrimental states like overcharge or overdischarge, and supports early fault detection. Our proposed KPCA-POA-BiGRU model offers a data-driven solution that avoids complex equivalent circuit modeling and parameter identification. By utilizing real-world experimental data from typical grid conditions, the model generalizes well to actual scenarios, providing a reliable tool for battery management systems (BMS). Future work could explore adaptive feature selection methods or integrate additional sensors to further enhance estimation precision. Additionally, extending the model to other battery chemistries or larger pack configurations could broaden its applicability in diverse battery energy storage systems.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel SOC estimation model for battery energy storage systems operating under peak shaving and frequency regulation conditions. By combining KPCA for feature reduction, BiGRU for temporal modeling, and POA for hyperparameter optimization, our approach achieves high accuracy and robustness. Experimental validation shows significant improvements over existing methods, with reduced errors and enhanced stability in mixed conditions. The dual-model strategy based on grid instructions further ensures reliable performance in real-time applications. This work contributes to the advancement of SOC estimation techniques, supporting the safe and efficient deployment of battery energy storage systems in modern power grids. As the demand for energy storage grows, such accurate monitoring tools will play a pivotal role in ensuring grid stability and longevity of storage assets.