In recent years, the growing global population and depletion of non-renewable resources have heightened awareness of efficient resource utilization, driving rapid development in new energy technologies. Among these, the lithium-ion battery stands out as a green energy source for the new century, prized for its high energy density, long service life, environmental friendliness, wide operating temperature range, and absence of memory effects. The anode material is a critical component in lithium-ion batteries, and since the advent of carbon-based graphite anodes, battery performance and safety have significantly improved. Carbon materials offer notable advantages in specific capacity, potential voltage, and cycling safety. However, capacity loss during charge-discharge cycles remains a limiting factor for advancing high-performance lithium-ion batteries. During charging, lithium plating often occurs, forming dendritic lithium枝晶 (lithium dendrites), which degrade battery performance, shorten cycle life, and limit fast-charging capacity. Dendrite growth stems from non-uniform Li⁺ deposition and uneven Li⁺ flux distribution on the anode surface. Enhancing the lithium-ion intercalation/deintercalation capability of battery separator materials is an effective strategy to suppress dendrite growth. Polyacrylonitrile (PAN), as a hard carbon material derived from organic pyrolysis, retains amorphous regions after carbonization, with disordered layer arrangements and numerous pores, providing ample space for Li⁺ storage and transport. PAN fibers exhibit high ionic conductivity, but their strong polar cyano (CN) groups have poor compatibility with lithium electrodes, leading to severe passivation. To address this, researchers have employed electrospinning to fabricate flexible and porous PAN-based electrolyte membranes with excellent electrochemical performance. Blending PAN with other polymers via electrospinning can also yield anode materials with superior cycling performance for lithium-ion batteries. In this study, we explore the preparation and properties of self-supporting carbon anode materials using PAN and cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) for lithium-ion batteries, focusing on the effects of CNCs addition and carbonization temperature.

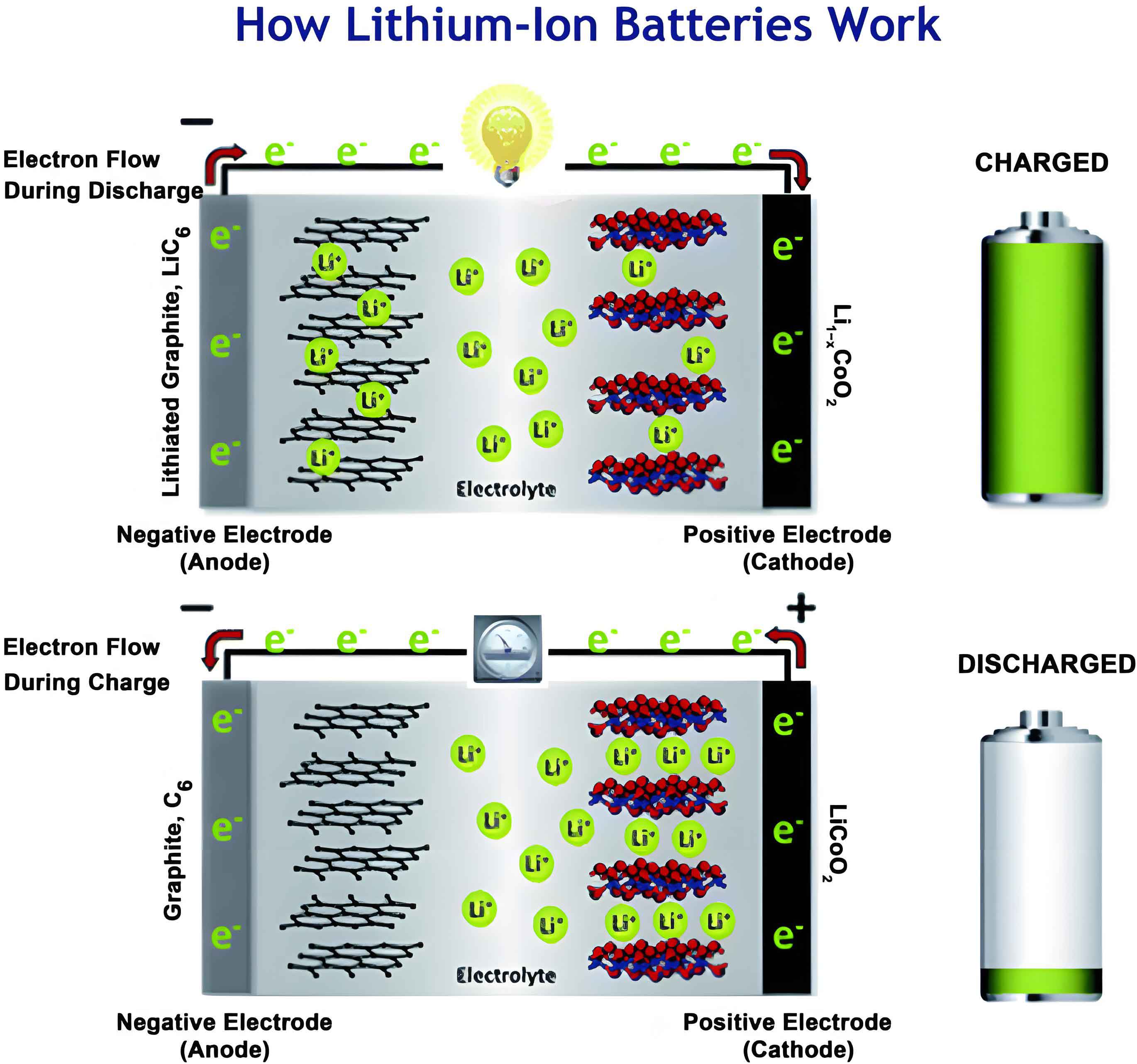

We begin by discussing the fundamentals of lithium-ion batteries. A typical lithium-ion battery consists of a cathode, anode, electrolyte, and separator. During discharge, Li⁺ ions move from the anode to the cathode through the electrolyte, while electrons flow through an external circuit, providing power. The anode material plays a crucial role in determining battery capacity, rate capability, and cycle life. Carbon-based materials, such as graphite, have been widely used due to their good conductivity and stability. However, graphite has a limited theoretical capacity of 372 mAh/g, prompting research into alternative carbon forms like hard carbon and soft carbon. Hard carbon, derived from precursors like PAN, features a turbostratic structure with nano-pores that can store additional Li⁺, potentially offering higher capacities. The reaction for lithium insertion into carbon can be represented as:

$$ \text{C} + x\text{Li}^+ + x\text{e}^- \leftrightarrow \text{Li}_x\text{C} $$

where $x$ depends on the carbon structure. For hard carbon, $x$ can exceed 1, leading to capacities above 372 mAh/g. The self-supporting design eliminates the need for binders and conductive additives, reducing weight and improving ion transport. Electrospinning is a versatile technique to produce nanofiber mats with high porosity and surface area, ideal for battery applications. In our work, we integrate CNCs—a green biomass-derived carbon source—with PAN to enhance the material’s properties. CNCs, with their high crystallinity and hydroxyl groups, can improve graphitization and interfacial compatibility when carbonized, forming soft carbon regions that tune the composite’s electrochemical behavior.

The preparation of PAN/CNCs composite fiber membranes involves several steps. First, we disperse CNCs in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and then add PAN in a mass ratio of 9:1 (PAN:CNCs), along with 1 wt% polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) as a dispersant. The mixture is stirred at 40°C for over 12 hours to ensure homogeneity. Electrospinning is performed at a voltage of 17 kV to produce the composite fiber membrane. After drying in a vacuum oven, the membrane is pre-oxidized at 240°C in a tube furnace to stabilize the structure. Subsequently, carbonization is carried out in an argon atmosphere at a flow rate of 200 mL/min, with a heating rate of 5°C/min, targeting temperatures of 700°C, 900°C, and 1000°C. The resulting self-supporting carbonized fiber membranes are cut into 12 mm diameter discs and dried at 100°C for 10 hours. For comparison, pure PAN carbonized fiber membranes are prepared under identical conditions. These membranes serve as anode materials in lithium-ion half-cells, assembled in an argon-filled glovebox using CR2032 coin cells. The assembly order is: positive case || anode (self-supporting carbonized fiber membrane) || separator (soaked with electrolyte) || lithium metal cathode || spacer || spring || negative case. The electrolyte is a mixture of 1 M LiPF₆ in EC:DMC:EMC (1:1:1 by volume). After assembly, cells are rested for 24 hours before testing.

To evaluate the performance, we conduct various tests. Wettability with the electrolyte is assessed using a contact angle goniometer. Electrochemical performance is analyzed via cyclic voltammetry (CV) from 0 to 2 V at a scan rate of 0.2 mV/s, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) over a frequency range of 1 to 10⁵ Hz with a 5 mV amplitude. Battery cycling performance is measured with a battery tester at 0.2 C rate (based on a nominal capacity of 300 mAh/g) within a voltage window of 0.01-3 V for 100 cycles. Rate capability is tested by cycling at 0.1 C, 0.2 C, 0.5 C, 1 C, 2 C, and then back to 1 C, 0.5 C, and 0.2 C, each for 10 cycles. Data are summarized using tables and formulas to provide clear insights.

The electrolyte wettability is crucial for ion transport in lithium-ion batteries. Contact angle measurements immediately upon electrolyte contact reveal that pure PAN carbonized membranes have angles of 12.4°, 15.2°, and 16.5° at 700°C, 900°C, and 1000°C, respectively. In contrast, PAN/CNCs membranes show slightly higher angles of 19.4°, 20.2°, and 21.0° at the same temperatures. This increase with carbonization temperature and CNC addition suggests enhanced graphitization, which reduces surface polarity. However, within 1 second, all membranes achieve complete wetting (contact angle ~0°), indicating good compatibility with the electrolyte. The improved wettability facilitates Li⁺ ion diffusion, essential for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. The data are summarized in Table 1.

| Material | Carbonization Temperature (°C) | Initial Contact Angle (°) | Wetting Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PAN | 700 | 12.4 | <1 |

| Pure PAN | 900 | 15.2 | <1 |

| Pure PAN | 1000 | 16.5 | <1 |

| PAN/CNCs | 700 | 19.4 | <1 |

| PAN/CNCs | 900 | 20.2 | <1 |

| PAN/CNCs | 1000 | 21.0 | <1 |

Electrochemical performance is evaluated through CV and EIS. CV curves for both materials show reduction peaks around 0.1 V, corresponding to Li⁺ insertion into carbon layers (forming LiₓC), and oxidation peaks near 1.2 V, representing LiₓC deintercalation. In the first discharge, a plateau at 0.5-1 V indicates solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) film formation. For PAN/CNCs membranes, the CV curves become more stable over cycles, with reduced irreversible capacity as carbonization temperature increases. At 1000°C, PAN/CNCs exhibits nearly overlapping curves after the first cycle, demonstrating superior cycling stability. This aligns with the role of CNCs in promoting structural order and reducing side reactions. The integral of the CV curve gives the charge stored, related to capacity by:

$$ Q = \int I \, dV $$

where $Q$ is charge and $I$ is current. The area under the reduction peak increases with CNC addition, suggesting enhanced Li⁺ storage. EIS spectra consist of a semicircle in the high-medium frequency region, representing charge transfer resistance ($R_{ct}$) and SEI film resistance ($R_{SEI}$), and a sloping line in the low-frequency region, indicating Warburg impedance ($Z_w$) for Li⁺ diffusion. The equivalent circuit can be modeled as:

$$ Z = R_s + \frac{1}{j\omega C_{dl} + \frac{1}{R_{ct}}} + \sigma \omega^{-1/2} $$

where $R_s$ is series resistance, $C_{dl}$ is double-layer capacitance, and $\sigma$ is Warburg coefficient. With CNC addition and higher carbonization temperatures, the semicircle diameter decreases, signifying lower $R_{ct}$ and $R_{SEI}$. This improves charge transfer kinetics, beneficial for fast-charging lithium-ion batteries. The Warburg impedance also reduces, indicating faster Li⁺ diffusion. Table 2 summarizes key EIS parameters extracted from fitting.

| Material | Carbonization Temperature (°C) | $R_s$ (Ω) | $R_{ct}$ (Ω) | $\sigma$ (Ω s^{-1/2}) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PAN | 700 | 2.5 | 85.3 | 25.6 |

| Pure PAN | 900 | 2.3 | 72.1 | 20.4 |

| Pure PAN | 1000 | 2.1 | 60.8 | 18.7 |

| PAN/CNCs | 700 | 2.4 | 78.2 | 22.9 |

| PAN/CNCs | 900 | 2.2 | 65.4 | 19.1 |

| PAN/CNCs | 1000 | 2.0 | 52.6 | 16.3 |

Cycling performance is critical for practical lithium-ion batteries. Initial charge-discharge curves show that pure PAN membranes have higher initial discharge capacities: 494.3 mAh/g at 700°C, 478.0 mAh/g at 900°C, and 305.9 mAh/g at 1000°C. PAN/CNCs membranes exhibit lower values: 448.0 mAh/g, 323.7 mAh/g, and 252.5 mAh/g, respectively. This decrease may stem from increased graphitization reducing amorphous carbon sites for Li⁺ storage. However, the first-cycle coulombic efficiency (CE) improves with CNC addition, calculated as:

$$ \text{CE} = \frac{\text{Charge Capacity}}{\text{Discharge Capacity}} \times 100\% $$

At 1000°C, PAN/CNCs achieves a CE of 67.58%, the highest among all samples. The discharge capacity can be expressed as:

$$ C = \frac{I \cdot t}{m} $$

where $C$ is specific capacity (mAh/g), $I$ is current (mA), $t$ is time (h), and $m$ is active mass (g). Over 100 cycles at 0.2 C, pure PAN membranes show capacity fading after 50 cycles, while PAN/CNCs maintain stability up to 90 cycles. At 1000°C, PAN/CNCs retains capacity without significant decay, indicating excellent cycle life. Coulombic efficiency trends reveal that PAN/CNCs has less fluctuation and approaches 100% at higher temperatures, due to stabilized SEI formation. Rate performance tests demonstrate that PAN/CNCs membranes suffer less capacity loss when cycled at increasing rates. For instance, at 900°C, pure PAN’s capacity drops by 48.8% from 0.1 C to 2 C, whereas PAN/CNCs retains 69.8% of its initial capacity. Upon returning to lower rates, PAN/CNCs recovers most of its capacity, highlighting good reversibility. This is attributed to the interconnected fibrous network from electrospinning and CNC-induced structural reinforcement, which enhance ionic and electronic conductivity. Table 3 summarizes cycling data.

| Material | Carbonization Temperature (°C) | Initial Discharge Capacity (mAh/g) | Initial Coulombic Efficiency (%) | Capacity Retention after 100 Cycles (%) | Rate Capability Retention (0.1 C to 2 C, %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure PAN | 700 | 494.3 | 58.2 | 65.4 | 45.2 |

| Pure PAN | 900 | 478.0 | 60.1 | 70.8 | 51.2 |

| Pure PAN | 1000 | 305.9 | 65.3 | 85.6 | 60.5 |

| PAN/CNCs | 700 | 448.0 | 61.5 | 75.9 | 58.7 |

| PAN/CNCs | 900 | 323.7 | 64.8 | 88.3 | 69.8 |

| PAN/CNCs | 1000 | 252.5 | 67.6 | 92.1 | 72.4 |

The enhanced performance of PAN/CNCs composites can be explained through material science principles. CNCs, as nanocrystalline cellulose, introduce hydroxyl groups that form hydrogen bonds with PAN, improving dispersion during electrospinning. Upon carbonization, CNCs decompose into soft carbon with higher graphitization degree, which integrates with the hard carbon matrix from PAN. This hybrid structure optimizes Li⁺ storage: the hard carbon regions provide nanopores for additional capacity, while the soft carbon regions enhance electrical conductivity and structural stability. The self-supporting design eliminates binder-related resistance, allowing direct electron pathways. Moreover, the fibrous morphology increases electrode-electrolyte contact area, facilitating faster ion transport. These factors collectively contribute to improved rate capability and cycling stability in lithium-ion batteries.

To quantify the benefits, we can model the capacity contribution. The total capacity ($C_{total}$) of the composite may be expressed as a weighted sum of hard carbon and soft carbon capacities:

$$ C_{total} = f_{HC} \cdot C_{HC} + f_{SC} \cdot C_{SC} $$

where $f_{HC}$ and $f_{SC}$ are mass fractions of hard carbon (from PAN) and soft carbon (from CNCs), and $C_{HC}$ and $C_{SC}$ are their respective specific capacities. For PAN/CNCs with 10% CNCs, $f_{SC} \approx 0.1$, and $C_{SC}$ is typically lower than $C_{HC}$ due to higher graphitization, explaining the slight capacity reduction. However, the soft carbon improves cycling efficiency by reducing irreversible reactions, as seen in higher CE. The diffusion coefficient of Li⁺ ($D_{Li^+}$) can be estimated from EIS using the Warburg coefficient:

$$ D_{Li^+} = \frac{R^2 T^2}{2 A^2 n^4 F^4 C^2 \sigma^2} $$

where $R$ is gas constant, $T$ is temperature, $A$ is electrode area, $n$ is number of electrons, $F$ is Faraday constant, and $C$ is Li⁺ concentration. With lower $\sigma$ for PAN/CNCs, $D_{Li^+}$ increases, confirming faster diffusion. This is vital for high-power lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles and portable electronics.

Further analysis involves the relationship between carbonization temperature and material properties. Higher temperatures promote graphitization, increasing sp² carbon content and conductivity. The degree of graphitization ($g$) can be estimated from X-ray diffraction, but here we infer it from electrochemical data. As temperature rises, the capacity decreases but stability improves, indicating a trade-off. For lithium-ion batteries, long-term cycle life is often prioritized over peak capacity, making PAN/CNCs at 1000°C a promising anode. Additionally, the SEI film formation is more stable on graphitic surfaces, reducing continuous electrolyte decomposition. The SEI resistance can be modeled as:

$$ R_{SEI} = \frac{\delta}{\kappa} $$

where $\delta$ is SEI thickness and $\kappa$ is ionic conductivity. With CNCs, $\delta$ may be more uniform due to better surface homogeneity, lowering $R_{SEI}$.

In practical applications, self-supporting carbon anodes like PAN/CNCs could simplify battery manufacturing by removing slurry casting steps. They also offer mechanical flexibility, suitable for flexible lithium-ion batteries in wearable devices. However, challenges remain, such as scaling up electrospinning and optimizing CNC loading. Future work could explore other biomass-derived additives or hybrid composites with metals (e.g., Sn, Si) to boost capacity further. The integration of such materials into full cells with commercial cathodes (e.g., LiFePO₄, NMC) is essential for real-world validation.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that PAN/CNCs self-supporting carbon anode materials exhibit excellent electrolyte wettability, stable electrochemical performance, and superior cycling stability compared to pure PAN counterparts in lithium-ion batteries. The addition of CNCs enhances graphitization, reduces charge transfer resistance, and improves coulombic efficiency, especially at higher carbonization temperatures. While specific capacity slightly decreases, the gains in cycle life and rate capability make these composites attractive for advanced lithium-ion batteries. Our findings highlight the potential of biomass-derived nanocellulose in tuning carbon anode properties, contributing to the development of sustainable and high-performance energy storage systems. Continued research in this area will further optimize materials for next-generation lithium-ion batteries, addressing global energy demands.