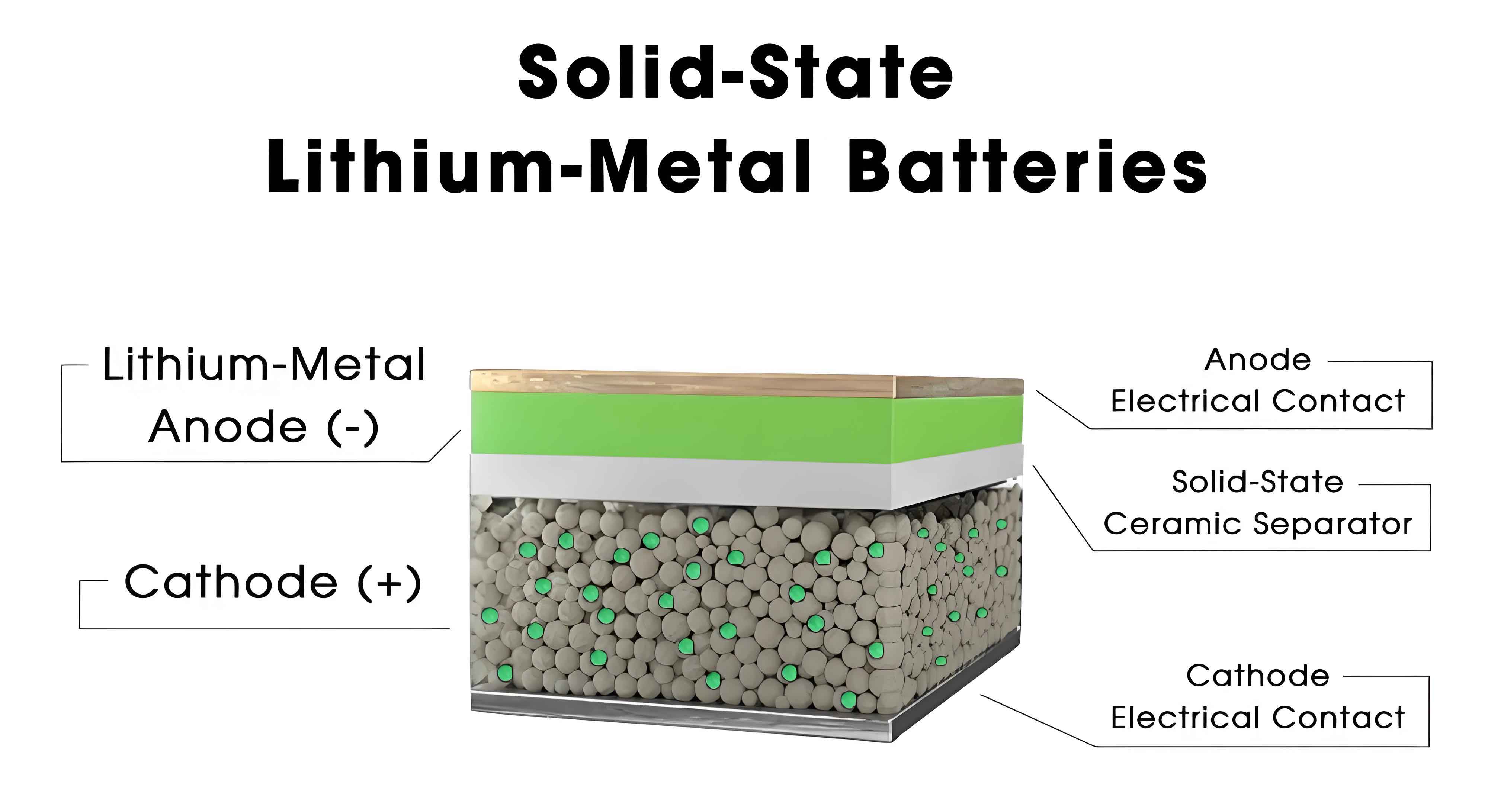

As we delve into the realm of next-generation electrochemical energy storage, all-solid-state lithium metal batteries have emerged as a pivotal technology due to their high theoretical energy density and enhanced safety prospects compared to conventional liquid electrolyte systems. However, the safety of these solid-state batteries remains a subject of intense scrutiny, primarily due to challenges such as lithium dendrite formation and complex interfacial reactions. In this comprehensive analysis, we explore the safety aspects of all-solid-state batteries from three critical perspectives: thermal stability of materials, mechanical stability, and interfacial reactions between the lithium metal anode and solid-state electrolyte. By synthesizing recent advancements, we aim to provide insights and guidance for developing intrinsically safe solid-state battery systems.

The transition to solid-state batteries is driven by the limitations of traditional lithium-ion batteries, including flammable organic electrolytes and dendrite-induced short circuits. Solid-state batteries, which utilize non-flammable solid electrolytes, promise to mitigate these risks. Nonetheless, the inherent properties of materials used in solid-state batteries—such as their thermal decomposition behavior, mechanical integrity under stress, and electrochemical interactions at interfaces—directly influence overall safety. We will systematically examine each of these factors, employing empirical data, theoretical models, and comparative analyses to underscore the progress and remaining hurdles in achieving safe all-solid-state lithium metal batteries.

Thermal Stability of Materials in All-Solid-State Batteries

Thermal stability is a cornerstone of battery safety, as excessive heat can trigger chain reactions leading to thermal runaway. In all-solid-state batteries, the thermal behavior of cathode materials, the lithium metal anode, and solid-state electrolytes dictates the system’s resilience to temperature fluctuations. We begin by evaluating the thermal properties of key components, using parameters such as the onset temperature of exothermic reactions (Tonset), peak temperature (Tpeak), and total heat release (ΔH). For instance, the thermal decomposition of cathode materials like LiNixCoyMnzO2 (NCM) and LiFePO4 (LFP) can initiate at temperatures as low as 200°C, releasing oxygen and exacerbating side reactions with solid electrolytes. The lithium metal anode, with a melting point of 180.5°C, poses a significant risk if localized hot spots develop, potentially causing structural failure.

Solid-state electrolytes exhibit varied thermal stabilities based on their composition. Sulfide-based electrolytes, such as Li6PS5Cl, may undergo decomposition above 200°C, while oxide electrolytes like Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO) demonstrate higher thermal resilience, with minimal exothermic activity up to 300°C. Polymer electrolytes, including poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) composites, can maintain stability beyond 300°C, but their performance is influenced by lithium salt interactions. To quantify these behaviors, we present a summary of thermal parameters in Table 1, which highlights the critical temperatures and heat release values for common materials in all-solid-state batteries.

| Material Type | Specific Material | Tonset (°C) | Tpeak (°C) | ΔH (J/g) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cathode | NCM111 | ~200 | ~250 | 350-500 | Oxygen release risk |

| Cathode | LiFePO4 | ~310 | ~400 | 200-300 | Higher stability |

| Anode | Lithium Metal | 180.5 (m.p.) | N/A | N/A | Melting point |

| Solid Electrolyte | Li6PS5Cl | ~200 | ~300 | 150-250 | Decomposition with Li |

| Solid Electrolyte | LLZO | >300 | >400 | <50 | High thermal inertia |

| Polymer Electrolyte | PEO-LiTFSI | >300 | >350 | 100-200 | Stable up to high T |

The thermal runaway process in all-solid-state batteries can be modeled using energy balance equations. For example, the heat generation rate during exothermic reactions can be expressed as:

$$ \frac{dQ}{dt} = A \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{RT}\right) \Delta H $$

where ( Q ) is the heat released, ( A ) is the pre-exponential factor, ( E_a ) is the activation energy, ( R ) is the gas constant, and ( T ) is temperature. This equation underscores the kinetic aspects of thermal decomposition, which are critical for predicting safety thresholds in solid-state battery designs. Furthermore, the integration of thermal management strategies, such as phase-change materials or thermally stable interfaces, can enhance the overall safety of all-solid-state batteries by delaying the onset of exothermic events.

Mechanical Stability of Materials in All-Solid-State Batteries

Mechanical integrity is essential for maintaining the structural coherence of all-solid-state batteries under operational stresses, including cycling-induced volume changes and external impacts. The lithium metal anode, despite its high theoretical capacity, is prone to dendrite formation, which can penetrate solid electrolytes and cause internal short circuits. We have observed that lithium dendrites often exhibit a hard, carbide-rich shell with a Young’s modulus exceeding that of bulk lithium, posing a threat to mechanical stability. Solid-state electrolytes, such as sulfides and oxides, must possess sufficient hardness and fracture toughness to resist dendrite penetration. For instance, garnet-type electrolytes like LLZO have a Young’s modulus of ~150 GPa, which is theoretically high enough to suppress dendrite growth, but practical issues like grain boundaries and pores can compromise this.

To assess mechanical properties, we consider parameters such as Young’s modulus (E), hardness (H), and fracture strength (σF). Cathode materials, including NCM and LFP, typically have E values ranging from 80 to 200 GPa, but cycling-induced cracking can reduce these values by up to 50% due to anisotropic expansion. This degradation is quantified by the relationship between fracture strength and grain size:

$$ \sigma_F \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{d}} $$

where ( d ) is the grain size. Reducing grain size or implementing textured structures can mitigate mechanical failure. For solid electrolytes, achieving high relative density (e.g., >95%) through high-pressure processing is crucial to minimize porosity and enhance dendrite resistance. Table 2 summarizes the mechanical properties of key materials, highlighting the importance of dense, defect-free microstructures for safe all-solid-state batteries.

| Material Type | Specific Material | Young’s Modulus (GPa) | Hardness (GPa) | Fracture Strength (MPa) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cathode | NCM622 | 120-180 | 8-12 | 100-200 | Cycle-dependent degradation |

| Cathode | LiFePO4 | 80-120 | 6-10 | 150-250 | More isotropic expansion |

| Anode | Lithium Metal | 4-8 | 0.1-0.5 | 10-50 | Low modulus, dendrite risk |

| Solid Electrolyte | LLZO | 140-160 | 10-15 | 200-300 | High dendrite resistance |

| Solid Electrolyte | Li3PS4 | 20-40 | 2-4 | 50-100 | Porous structures vulnerable |

| Polymer Electrolyte | PEO-Based | 0.1-1 | 0.01-0.1 | 5-20 | Flexible but weak |

In addition, the fatigue behavior of lithium metal in contact with solid electrolytes plays a critical role in long-term stability. Recent studies indicate that cyclic stresses during charge-discharge can lead to micro-void formation and interface degradation, even at low current densities. The fatigue life (Nf) can be estimated using models that account for stress amplitude (Δσ) and lithium diffusion coefficients (DLi):

$$ N_f = C \left( \frac{\Delta \sigma}{E} \right)^{-b} \exp\left(-\frac{Q}{RT}\right) $$

where ( C ) and ( b ) are material constants, and ( Q ) is the activation energy for diffusion. Enhancing the mechanical stability of all-solid-state batteries requires a multifaceted approach, including the development of composite electrolytes and 3D host structures for lithium, which we will explore in subsequent sections.

Interfacial Reactions Between Lithium Metal Anode and Solid-State Electrolyte

The interface between the lithium metal anode and solid-state electrolyte is a hotspot for chemical and electrochemical reactions that govern the safety and performance of all-solid-state batteries. Lithium metal, being highly reducing, can degrade most solid electrolytes, forming interphases that influence ionic and electronic conductivity. We categorize these interfacial phases into three types: Type I (thermodynamically stable), Type II (electronically insulating solid electrolyte interphase, SEI), and Type III (electronically conductive). For instance, sulfide electrolytes like Li3PS4 often form Type III interfaces with conductive species such as Li3P, which can facilitate lithium deposition within the electrolyte, leading to dendrites and short circuits.

The electrochemical stability window of a solid-state electrolyte determines its compatibility with electrodes. It can be expressed as:

$$ E_{\text{window}} = E_{\text{cathode}} – E_{\text{anode}} $$

where ( E_{\text{cathode}} ) and ( E_{\text{anode}} ) are the equilibrium potentials of the cathode and anode, respectively. However, kinetic factors often widen the practical window due to slow decomposition rates. For example, LLZO has a theoretical window of ~0-5 V vs. Li/Li+, but interface formation can extend its usability. To mitigate interfacial issues, strategies such as artificial interlayers (e.g., LiF or Li3N coatings) and in situ polymerization of polymer electrolytes have been developed. These approaches reduce the interfacial resistance (Rint), which is critical for high-rate performance and can be modeled as:

$$ R_{\text{int}} = \frac{\delta}{\sigma_{\text{ion}} A} $$

where ( \delta ) is the interphase thickness, ( \sigma_{\text{ion}} ) is the ionic conductivity, and ( A ) is the effective contact area. Increasing ( A ) through 3D electrolyte designs or surface treatments can significantly lower Rint, as demonstrated by studies where vacuum-deposited lithium on LLZO reduced Rint from 746 Ω·cm² to 69 Ω·cm².

Table 3 provides a comparative analysis of interfacial properties for different solid-state electrolyte systems, emphasizing the impact of interface engineering on the safety of all-solid-state batteries. For instance, polymer-based solid electrolytes exhibit excellent interfacial compatibility but may suffer from low ionic conductivity at room temperature, whereas sulfide electrolytes offer high conductivity but require careful interface control to prevent degradation.

| Electrolyte Type | Specific Material | Interfacial Phase Type | Ionic Conductivity (S/cm) | Electronic Conductivity (S/cm) | Interfacial Resistance (Ω·cm²) | Safety Implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfide | Li6PS5Cl | III (Conductive) | 10−2 to 10−3 | 10−5 to 10−7 | 50-200 | Dendrite risk, needs coating |

| Oxide | LLZO | II (SEI-forming) | 10−4 to 10−3 | <10−10 | 70-500 | Stable with treatments |

| Halide | Li3YCl6 | I/II Mixed | 10−3 to 10−4 | <10−8 | 100-300 | Good oxidation stability |

| Polymer | PEO-LiTFSI | II (SEI-forming) | 10−4 to 10−5 | <10−10 | 20-100 | Flexible, low dendrite risk |

| Composite | LLZO-PVDF | II (SEI-forming) | 10−3 to 10−4 | <10−9 | 30-150 | Enhanced mechanical strength |

Furthermore, the dynamics of lithium plating and stripping at interfaces involve complex phenomena such as concentration gradients and stress evolution. The lithium ion flux (JLi) across the interface can be described by the Nernst-Planck equation:

$$ J_{\text{Li}} = -D_{\text{Li}} \nabla C_{\text{Li}} + \frac{zF}{RT} D_{\text{Li}} C_{\text{Li}} \nabla \phi $$

where ( D_{\text{Li}} ) is the diffusion coefficient, ( C_{\text{Li}} ) is the lithium concentration, ( z ) is the charge number, ( F ) is the Faraday constant, and ( \phi ) is the electric potential. Non-uniform lithium deposition, driven by localized high current densities, can lead to dendrite formation, emphasizing the need for homogeneous interfaces in all-solid-state batteries. Advanced characterization techniques, such as in situ neutron depth profiling, have revealed that lithium dendrites can nucleate within solid electrolytes if the electronic conductivity exceeds 10−10 S/cm, highlighting the importance of material purity and processing.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

In summary, the safety of all-solid-state lithium metal batteries is intricately linked to the thermal and mechanical stability of their components, as well as the electrochemical behavior at interfaces. While solid-state batteries offer a promising path toward safer energy storage, challenges such as lithium dendrite penetration, interfacial degradation, and material-specific thermal risks necessitate continued research and innovation. We have discussed how high-density solid electrolytes, engineered interfaces, and advanced host matrices can mitigate these issues, but practical implementation requires a holistic approach that balances performance with safety.

Looking ahead, we envision several key directions for developing intrinsically safe all-solid-state batteries. First, optimizing sulfide-based solid electrolytes for higher relative density (>95%) and lower electronic conductivity could significantly reduce dendrite formation. Second, incorporating carbon-based host structures for lithium metal anodes may enhance deposition uniformity without compromising energy density. Third, interface design through in situ polymerization or artificial layers should focus on creating ion-conductive, electron-blocking interphases to prevent continuous degradation. Additionally, the integration of thermal management systems and fatigue-resistant materials will be crucial for long-term cyclability. Finally, standardized safety testing protocols, including abuse tolerance assessments under varied conditions, will accelerate the commercialization of all-solid-state batteries.

As we advance, interdisciplinary collaborations combining materials science, electrochemistry, and engineering will be essential to overcome the remaining barriers. The progress in all-solid-state battery technology holds the potential to revolutionize energy storage for applications ranging from electric vehicles to grid storage, but only if safety is prioritized at every stage of development. By building on the insights presented here, we can move closer to realizing the full promise of all-solid-state lithium metal batteries as a safe, high-energy-density solution for the future.