We present a comprehensive review of small-signal stability issues in grid-connected battery energy storage systems (BESS). The increasing penetration of renewable energy sources necessitates large-scale energy storage to mitigate power fluctuations and provide grid support. The widespread integration of battery energy storage systems introduces new dynamic interactions that challenge the stability of both AC and DC power networks. This review aims to clarify the unique stability risks associated with battery energy storage systems, differentiating them from conventional renewable energy inverters, and to identify gaps in current research, particularly concerning their bidirectional power capability, control diversity, and the challenges of large-scale deployment.

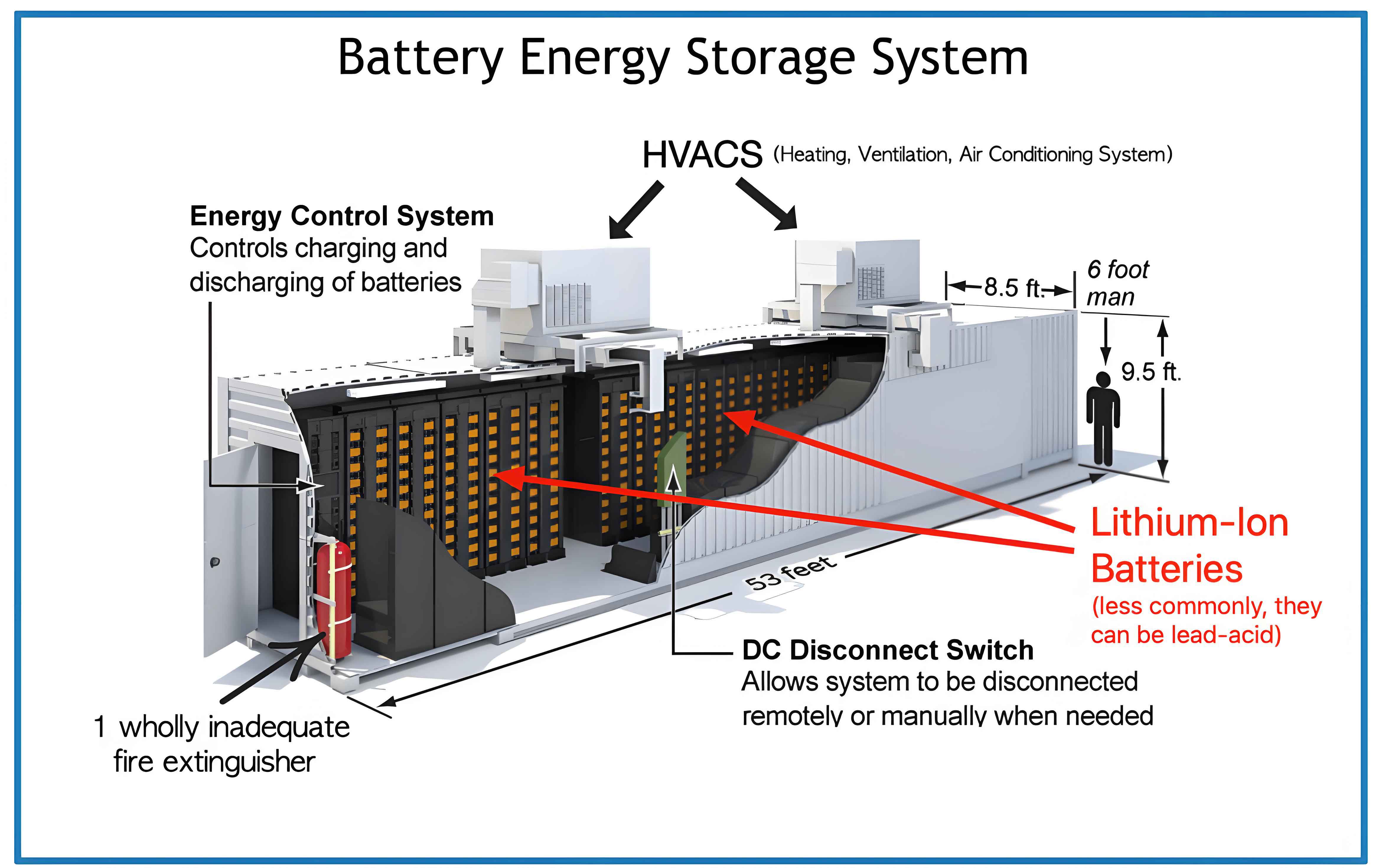

The fundamental architecture of a battery energy storage system comprises the battery pack itself and the power electronic converters required for grid interfacing. A battery pack is constructed by connecting numerous individual cells in series and parallel to meet voltage, current, and capacity requirements. For stability studies in the small-signal domain (typically second-scale dynamics), the electrochemical dynamics of the battery can be simplified to a constant voltage source $V_0$ in series with an internal resistance $R_0$.

The core of the battery energy storage system is its power conversion system, which can be a DC/AC converter for AC grid connection, or a combination of DC/DC and DC/AC converters. The control strategies applied to these converters are pivotal in determining the system’s dynamic behavior and stability characteristics.

The control strategies for a battery energy storage system vary significantly depending on the grid type (AC or DC) and the desired functionality. In DC systems, the DC/DC converter is typically controlled in one of three primary modes: Constant Current (CC), Constant Voltage (CV), or Constant Power (CP) control. The CP control is particularly critical for stability analysis as it alters the intrinsic source characteristic of the battery.

When connected to AC systems, the battery energy storage system’s DC/AC converter can operate under two broad control paradigms: Grid-Following (GFL) and Grid-Forming (GFM) control. Grid-following control relies on a Phase-Locked Loop (PLL) for synchronization and typically uses cascaded outer and inner loops to regulate power or voltage. Grid-forming control, in contrast, autonomously establishes the voltage and frequency of the grid, mimicking the behavior of a synchronous generator, and does not require a PLL for synchronization. A key distinction between a battery energy storage system and a renewable energy source like a photovoltaic (PV) inverter is the control objective. A PV inverter under Maximum Power Point Tracking (MPPT) must regulate its DC-link voltage, acting as a power balance node. A battery energy storage system, with its inherent energy reserve, can have control objectives focused on active power or frequency, enabling diverse support functions like oscillation damping and inertia emulation. This control diversity is a defining feature of the modern battery energy storage system.

The differences between a typical battery energy storage system and a renewable energy source are summarized in the table below.

| Component | Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) | Renewable Energy (e.g., PV, Wind) |

|---|---|---|

| Source-Side Characteristic | Constant Voltage (simplified), with options for Constant Current or Constant Power control via DC/DC converter. | Variable power source; typically operated at Maximum Power Point (MPPT), acting as a constant power source in dynamics. |

| Grid-Side Converter Control | Grid-Following or Grid-Forming control. Control objectives can be power, frequency, or voltage. | Predominantly Grid-Following control. Control must involve DC-link voltage regulation under MPPT. Grid-Forming control is challenging without an附加 energy buffer. |

| Power Flow | Bidirectional (Charge/Discharge). | Unidirectional (Generation only). |

| Primary Function | Energy time-shift, grid support, frequency regulation, stability enhancement. | Energy generation. |

Impact of Battery Energy Storage Systems on DC System Stability

The integration of a battery energy storage system into a DC network introduces specific stability challenges primarily related to the interaction between the converter’s input impedance and the network impedance. The general process for analyzing these interactions often involves impedance-based or state-space model-based methods.

The stability of a single grid-connected battery energy storage system in a DC network is influenced by factors such as battery parameters, control parameters of the DC/DC converter, and the direction of power flow. When detailed dynamics of the battery and its controller are considered, modal or time-domain analysis is typically employed. However, to gain intuitive physical insight, especially concerning the Constant Power Load (CPL) instability phenomenon, the battery energy storage system under constant power control is often simplified. In this simplified model, the battery energy storage system is treated as an ideal constant power sink (when charging) or source (when discharging).

For a simplified battery energy storage system model with constant power control, the input impedance $Z_{in}$ can be derived. Let $P_{dc} = V_{dc} I_{dc}$ be the terminal power. For a constant power device, $\Delta P_{dc} = 0$. Linearizing the power equation gives:

$$\Delta P_{dc} = I_{dc0} \Delta V_{dc} + V_{dc0} \Delta I_{dc} = 0$$

where $V_{dc0}$ and $I_{dc0}$ are the steady-state operating point values. Solving for the impedance yields:

$$Z_{in} = \frac{\Delta V_{dc}}{\Delta I_{dc}} = -\frac{V_{dc0}}{I_{dc0}}$$

This result shows that a battery energy storage system operating in constant power charging mode ($I_{dc0} > 0$) presents a negative incremental impedance to the DC network. This negative impedance can interact with the network’s LC filters or source impedances to create positive feedback, leading to instability (voltage oscillations). Conversely, in constant power discharging mode ($I_{dc0} < 0$), it presents a positive impedance. This fundamental mechanism highlights a key instability risk unique to bidirectional power devices like a battery energy storage system.

It is crucial to note that this simplified model ignores the internal dynamics of the battery pack and the bandwidth limits of the power converter’s control loops. The error introduced by this simplification, $\Delta Z = Z_{detailed}(s) – Z_{simplified}$, may accumulate when scaling up the system model, potentially leading to misjudgment of stability margins. Quantifying this error and establishing the conditions under which the simplification is valid remain important research questions for accurately assessing the stability of large-scale battery energy storage system deployments.

For systems with multiple battery energy storage systems, the configuration (parallel, cascaded, or distributed) significantly impacts the analysis. For $N$ identical battery energy storage systems in parallel, the aggregate equivalent input impedance is approximately $Z_{agg} = Z_{in} / N$. For cascaded configurations, the equivalent impedance becomes more complex. While parallel and cascaded arrays of identical units can be aggregated, a general DC microgrid with multiple, heterogeneously controlled battery energy storage systems distributed across different nodes represents a multi-input-multi-output (MIMO) system. Traditional single-input-single-output (SISO) impedance analysis becomes inadequate, and generalized Nyquist or modal analysis methods are required, posing significant computational and analytical challenges for large-scale systems.

Impact of Battery Energy Storage Systems on AC System Stability

The impact of a battery energy storage system on AC grid stability is more complex due to the higher order dynamics of AC synchronization, the diversity of control strategies (GFL vs. GFM), and the bidirectional power flow capability.

For a grid-following battery energy storage system, many stability issues are analogous to those of renewable energy inverters, such as:

- Weak-Grid Instability: Caused by adverse interactions between the PLL and the grid impedance under high power output and low short-circuit ratio (SCR) conditions.

- Sub-synchronous/Super-synchronous Oscillations: Resulting from dynamic interactions between the converter controls and series-compensated transmission lines or other resonant elements in the grid.

- High-Frequency Resonance: Due to the interaction between the converter output impedance and grid impedance at harmonic frequencies.

However, the battery energy storage system introduces the critical factor of power flow direction. The damping contribution or negative resistance effect of a GFL inverter can change sign depending on whether it is injecting (generating) or absorbing (load) power. This adds a layer of complexity to stability analysis not present with unidirectional renewable sources.

Furthermore, the simplified constant-power model analysis can be extended to the AC case. Assuming a GFL converter with perfect power control ($\Delta P=0, \Delta Q=0$) and a perfectly aligned reference frame ($V_{sq}=0$), the simplified $dq$-frame input impedance matrix $Z_{dq}^{in}$ can be derived. Linearizing the power equations:

$$

\Delta P_s = I_{sd0} \Delta V_{sd} + V_{sd0} \Delta I_{sd} = 0

$$

$$

\Delta Q_s = -I_{sq0} \Delta V_{sq} – V_{sq0} \Delta I_{sq} = 0 \quad \text{(with $V_{sq0}=0$)}

$$

If the converter primarily handles active power ($I_{sq0} \approx 0$), solving yields:

$$Z_{dq}^{in} \approx \begin{bmatrix} -V_{sd0}/I_{sd0} & 0 \\ 0 & -V_{sd0}/I_{sd0} \end{bmatrix}$$

Again, this indicates a negative resistance behavior in the active power charging state ($I_{sd0}>0$), which can destabilize certain AC network modes.

Grid-forming battery energy storage systems, such as those employing Virtual Synchronous Generator (VSG) control, eliminate PLL-related instability but introduce new dynamics akin to synchronous machines. The primary stability concerns for GFM converters include:

- Low-Frequency Oscillations (LFO): GFM converters interact with synchronous generators and other GFM units, potentially inducing or exacerbating electromechanical oscillation modes (e.g., 0.1-2 Hz). The virtual inertia and damping coefficients are key parameters affecting this interaction.

- Synchronization Stability: Similar to the rotor angle stability of synchronous machines, GFM converters must maintain synchronization with the grid under large disturbances.

- Current Limiting Interactions: The transition into and out of current saturation during faults can lead to unstable post-fault recovery.

The stability analysis of GFM-based battery energy storage systems often employs state-space modal analysis or complex torque coefficients approach, moving beyond the impedance methods more common for GFL systems.

A significant challenge arises in systems with multiple interacting battery energy storage systems. The dynamic interaction between two or more BESS units, especially if they have different control types (GFL vs. GFM) or are operating in different power flow states, can create complex oscillatory modes. Analyzing these interactions in a large-scale AC grid with distributed battery energy storage systems requires advanced MIMO stability theory. The concept of “open-loop modal resonance” has been used to explain how the dynamic modes of two subsystems can attract and repel each other, potentially reducing damping. The scaling of such phenomena with the number of battery energy storage system units is not yet well understood.

Summary and Future Research Directions

This review has synthesized the current understanding of small-signal stability in grid-connected battery energy storage systems. Key conclusions are:

- The unique characteristics of a battery energy storage system—particularly its bidirectional power capability and diverse control objectives—differentiate its stability impact from that of traditional renewable energy sources. The constant-power-load-induced negative impedance effect is a fundamental instability mechanism, especially relevant in DC systems and for charging BESS in AC systems.

- Research on single battery energy storage system integration is mature, employing established methods like impedance analysis and modal analysis. However, common modeling simplifications (e.g., ideal constant power source, neglecting detailed battery dynamics) may lead to error accumulation in stability assessment for large-scale systems. The validity conditions and error bounds for these simplifications need systematic quantification.

- The stability analysis of large-scale battery energy storage system integration, involving multiple heterogeneous units in complex AC/DC networks, presents significant methodological challenges. Traditional SISO techniques are insufficient, and scalable MIMO stability analysis frameworks are urgently needed.

Based on the identified gaps, we outline critical future research directions:

| Research Area | Specific Challenges | Potential Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Modeling Fidelity & Simplification | Quantifying the error and establishing validity boundaries of simplified BESS models (e.g., constant power source) for stability studies. |

|

| Large-Scale System Analysis | Lack of efficient and insightful stability analysis methods for grids with many distributed, heterogeneous battery energy storage systems. |

|

| Control Diversity & Interaction | Understanding and mitigating adverse dynamic interactions between battery energy storage systems with different controls (GFL/GFM/mixed) and between battery energy storage systems and legacy generation. |

|

Addressing these challenges is essential for ensuring the reliable and stable operation of future power systems with deep penetration of battery energy storage systems. As the scale of deployment grows, moving from analyzing single units to understanding the collective behavior of a fleet of battery energy storage systems will be paramount. This requires a concerted effort in developing new analytical tools, high-fidelity yet tractable models, and coordination strategies that harness the flexibility of the battery energy storage system while safeguarding grid stability.