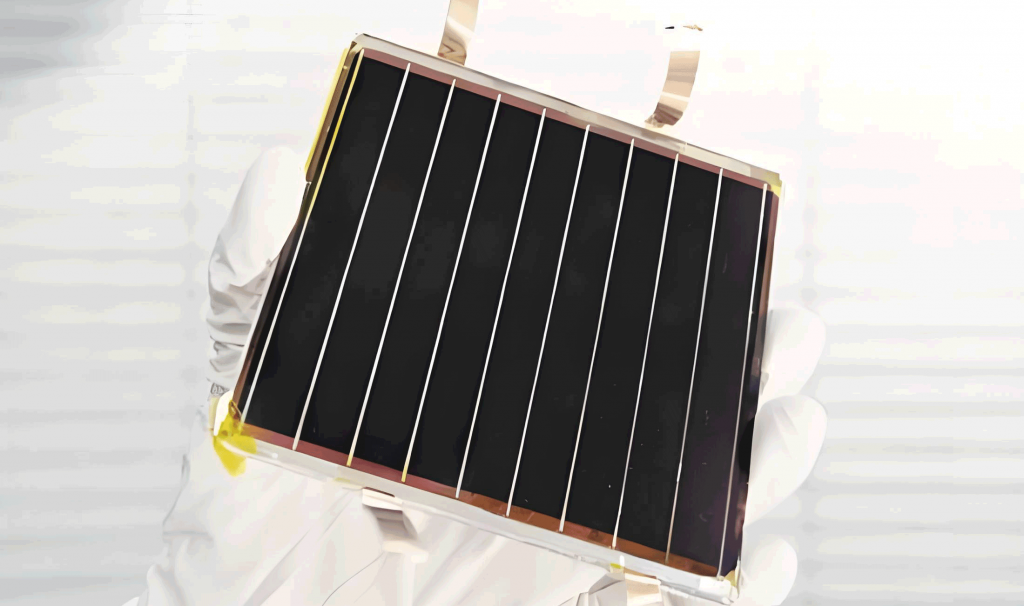

In recent years, perovskite solar cells have garnered significant attention due to their exceptional photoelectric conversion performance, with laboratory-scale devices achieving efficiencies exceeding 26%. The core of these devices lies in the perovskite light-absorption layer, whose quality directly impacts the overall performance. Among various fabrication methods, the two-step spin-coating solution process stands out for its simplicity, reproducibility, and operational flexibility, making it highly promising for scalable production of high-quality perovskite films. This method involves depositing an inorganic layer (e.g., PbI₂) followed by an organic salt solution (e.g., formamidinium iodide, FAI), allowing controlled crystallization and reduced defects compared to one-step methods. However, challenges such as incomplete PbI₂ conversion and rapid crystallization kinetics persist. This article comprehensively reviews recent progress in additive engineering, interface modification, solvent engineering, and other strategies for optimizing two-step spin-coated formamidinium lead-based perovskite solar cells, with a focus on enhancing efficiency and stability for commercial applications.

The two-step method decouples the perovskite formation process, enabling finer control over nucleation and growth. The reaction between PbI₂ and organic salts is governed by solid-liquid interactions and dissolution-recrystallization mechanisms. Early studies demonstrated that porous PbI₂ layers facilitate complete conversion, while additives can modulate crystallization rates and passivate defects. For instance, the incorporation of AtaCl in PbI₂ solutions promotes the formation of loose, porous structures, enhancing organic salt diffusion and reducing residual PbI₂. Similarly, interfacial treatments with materials like CsF or ZIF-8@FAI capsules improve charge transport and stability. This review delves into these strategies, providing insights into their mechanisms and impacts on perovskite solar cell performance.

Additive Engineering in Two-Step Spin-Coating

Additive engineering is a pivotal approach for optimizing perovskite solar cells, as it can passivate defects, modulate crystallization, and improve stability. Based on the incorporation site, additives are categorized into those introduced in inorganic components, organic components, and charge transport layers.

Additives in Inorganic Components

In the two-step process, the morphology of the PbI₂ layer critically influences the subsequent reaction with organic salts. A porous PbI₂ structure allows efficient penetration of organic cations, promoting complete conversion to perovskite and minimizing residual PbI₂. Excessive PbI₂ can lead to defect states and non-radiative recombination, while controlled amounts may passivate defects and enhance stability. Various additives have been explored to tailor PbI₂ film properties.

For example, AtaCl additive induces a fluffy and porous PbI₂ layer, as illustrated in SEM images, which facilitates FAI diffusion and complete conversion. The resulting perovskite films exhibit larger grain sizes and reduced defect density. Similarly, NaHCO₃ treatment creates porous PbI₂ structures, enabling better organic salt infiltration and improved crystallinity. Other additives, such as HMPA and UiO-66, alter PbI₂ morphology to enhance reactivity. The table below summarizes key additives, device structures, efficiencies, and publication dates.

| Additive Material | Device Structure | Area (cm²) | PCE (%) | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SA | ITO/SnO₂//FAₓMA₁₋ₓPbI₃/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | 0.04 | 23.56 | 2023.1.7 |

| EMIMBF₄ | ITO/SnO₂/FAₓMA₁₋ₓPbI₃/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | 0.04 | 24.28 | 2023.11.22 |

| GBA | FTO/c-TiO₂/FA₀.₉₈MA₀.₀₂PbI₃/o-F-PEAI/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 0.08 | 25.32 | 2023.9.28 |

| CsX | ITO/SnO₂/CsX Perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | 0.09 | 20.29 | 2023.5.13 |

| EuBr₂ | ITO/SnO₂/perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 0.089 | 23.04 | 2024.1.1 |

Crystal growth modulation is another key aspect. Additives like EHA with multidentate coordination pre-aggregate PbI₂ colloids, facilitating oriented crystallization and defect passivation. The crystallization process can be described by the Gibbs free energy equation: $$\Delta G = \Delta H – T\Delta S$$ where $\Delta G$ is the change in Gibbs free energy, $\Delta H$ is the enthalpy change, $T$ is temperature, and $\Delta S$ is the entropy change. Additives that lower $\Delta G$ promote spontaneous perovskite formation. For instance, PFAT reduces the Gibbs free energy of PbI₂ clusters, enabling secondary growth and early perovskite phase formation.

Furthermore, additives such as RbCl and MDACl₂ synergistically regulate crystal growth, improving crystallinity and orientation. Hydantoin, as a crystallization modulator, leverages its functional groups to form high-quality films with low defect density, achieving efficiencies up to 25.66%. These strategies highlight the importance of additive selection in optimizing inorganic precursor layers for high-performance perovskite solar cells.

Additives in Organic Components

The rapid reaction between FAI and PbI₂ often leads to the formation of a dense perovskite layer on the surface, hindering further diffusion of organic cations into the PbI₂ lattice. This results in small grain sizes and concentrated defects. Additives in organic salt solutions can slow down the reaction kinetics, enabling larger grains and reduced defect density.

For example, FBAD interacts with FAI to suppress the rapid reaction with PbI₂, passivating uncoordinated Pb²⁺ or I⁻ defects. This results in α-FAPbI₃ films with low defect density and large grains. TEMPO radicals eliminate iodine-deficient phases and passivate defects, enhancing photostability and achieving 25.03% PCE. The table below summarizes additives in organic components.

| Additive Material | Device Structure | Area (cm²) | PCE (%) | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3Cl-BZH | ITO/RbF-SnO₂/CsFAMAPVK/NMABr/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | Unknown | 24.08 | 2023.11.13 |

| PAA | FTO/SnO₂/Perovskite/OAI/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | 0.0514 | 24.19 | 2023.2.28 |

| HFB | FTO/SnO₂/FAPbI₃/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 0.0831 | 26.07 | 2023.11.16 |

| SEH+AM1 | Glass/FTO/SnO₂/perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | Unknown | 20.10 | 2023.1.4 |

| FS-3100 | FTO/SnO₂/perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 0.16 | 21.72 | 2023.6.7 |

Solvent-additive interactions can be modeled using coordination chemistry. For instance, HFB regulates reaction kinetics via anion-π interactions, leading to phase-pure α-FAPbI₃ with minimal defects. The reaction rate constant $k$ can be expressed as: $$k = A e^{-E_a/(RT)}$$ where $A$ is the pre-exponential factor, $E_a$ is the activation energy, $R$ is the gas constant, and $T$ is temperature. Additives that increase $E_a$ slow down the reaction, allowing controlled crystallization.

Ionic liquids (ILs) with small anions, such as TFSI⁻, fill halide vacancies and reduce defect density, improving carrier lifetime and device performance. The “slow-release effect” of PAA delays organic salt aggregation, promoting uniform perovskite growth. These approaches demonstrate the versatility of organic component additives in enhancing perovskite solar cell efficiency and stability.

Additives in Charge Transport Layers

Charge transport layers, including electron transport layers (ETLs) and hole transport layers (HTLs), play a crucial role in extracting and transporting carriers while minimizing recombination. Additives in these layers can optimize energy level alignment, reduce interface defects, and enhance conductivity.

For ETLs, SnO₂ is commonly used due to its high electron mobility and low-temperature processability. Incorporating PAA into SnO₂ precursors improves wettability and film quality, leading to a PCE increase from 15.7% to 17.2%. Tungsten ammonium hydrate-doped SnO₂ enhances conductivity and electron extraction, boosting PCE to 21.83%. FOA additive in SnO₂ forms a gradient distribution at the buried interface, passivating defects and improving energy level matching, resulting in 25.05% PCE.

For HTLs, Spiro-OMeTAD is widely employed. Adding CMABr to Spiro-OMeTAD solutions reacts with residual PbI₂ to form a 2D perovskite interlayer, acting as a moisture barrier and reducing non-radiative recombination. This strategy achieves 23.56% PCE. The table below summarizes additives in charge transport layers.

| Type | Additive Material | Device Structure | Area (cm²) | PCE (%) | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETL | FOA | ITO/SnO₂/perovskite/SpiroOMeTAD/MoO₃/Ag | 0.037 | 25.05 | 2023.7.17 |

| ETL | FAI+CsBr | Glass/ITO/SnO₂/Perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 0.0928 | 24.26 | 2023.3.23 |

| ETL | PAA | FTO/PAA@SnO₂/(FAPbI₃)₀.₉₇(MAPbBr₃)₀.₀₃/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | Unknown | 17.2 | 2024.1.9 |

| ETL | (NH₄)₁₀W₁₂O₄₁•xH₂O | FTO/SnO₂/Perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 0.1 | 21.83 | 2024.1.18 |

| HTL | CMABr | FTO/compactTiO₂/triple-cation perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD with and without CMABr/Au | 0.125 | 23.56 | 2022.10.22 |

The charge extraction efficiency can be described by the equation: $$\eta_{ext} = \frac{J_{sc}}{q G L}$$ where $J_{sc}$ is the short-circuit current density, $q$ is the electron charge, $G$ is the generation rate, and $L$ is the diffusion length. Additives that reduce interface recombination and improve carrier mobility enhance $\eta_{ext}$, directly impacting the perovskite solar cell performance.

Interface Modification Strategies

Interface modification is critical for reducing non-radiative recombination and enhancing charge transport in perovskite solar cells. Key interfaces include the ETL/perovskite and perovskite/HTL interfaces. Passivation techniques involve surface treatments to optimize energy level alignment and defect passivation.

For the ETL/perovskite interface, CH₃COOK treatment on SnO₂ reduces PbI₂ residue and improves crystallinity. CsF interlayers release interface stress and adjust SnO₂ energy levels, achieving 23.13% PCE. ZIF-8@FAI capsules incorporate FAI and ZIF-8 to enhance UV resistance and strain release, leading to 24.08% PCE. The schematic of the two-step deposition process with ZIF-8@FAI illustrates the improved film formation.

FSA bifunctionalization optimizes SnO₂ energy levels and reduces deep-level defects, resulting in 24.1% PCE and long-term stability. KFSI salts leverage fluorine and sulfonyl groups for synergistic passivation, achieving 24.17% PCE. Bilayer SnO₂ structures combining ALD and solution-processed SnO₂ improve substrate coverage and reduce roughness, facilitating PbI₂ growth and enhancing efficiency.

For the perovskite/HTL interface, 2-Br-PEAI forms a 2D perovskite layer that passifies defects and reduces non-radiative recombination. Starch-polyiodide supramolecular buffers inhibit ion migration and promote defect self-healing, maintaining 98% initial efficiency after light-dark cycling. HTAB modification on the perovskite/P3HT interface increases grain size and reduces defects, achieving 16.08% PCE in carbon-based devices.

The interface recombination velocity $S$ can be expressed as: $$S = \sigma v_{th} N_t$$ where $\sigma$ is the capture cross-section, $v_{th}$ is the thermal velocity, and $N_t$ is the interface trap density. Passivation strategies that reduce $N_t$ lower $S$, improving open-circuit voltage and fill factor in perovskite solar cells.

Further studies on conjugated organic cations like Cl₄Tm enable stable 2D/3D heterojunctions with fine energy level tuning, achieving 24.6% PCE. Full-interface passivation with OAI and GACl creates an n-i-p five-layer structure, yielding 25.43% PCE. These advancements underscore the importance of comprehensive interface engineering in perovskite solar cell development.

Solvent Engineering and Other Modulation Approaches

Solvent engineering involves optimizing the solvent system to control perovskite crystallization and film formation. In two-step methods, solvents not only dissolve precursors but also interact with organic ammonium or Pb²⁺ cations, influencing crystal growth and morphology.

For instance, adjusting the ethanol/methanol ratio in CsI solutions modulates CsI solubility, enabling high-quality FA₁₋ₓCsₓPbI₃ films with low defect density and long carrier lifetime, achieving 21.17% PCE. The solvent polarity can be described by the Hansen solubility parameters: $$\delta_t^2 = \delta_d^2 + \delta_p^2 + \delta_h^2$$ where $\delta_d$, $\delta_p$, and $\delta_h$ represent dispersion, polar, and hydrogen bonding components, respectively. Solvents with optimal $\delta_t$ values promote uniform precursor dissolution and controlled crystallization.

Other modulation strategies include using polarized ferroelectric polymers like P(VDF-TrFE) to alter surface potential distribution and enhance carrier transport via the piezophototronic effect. PbI₂ powder particle size also affects film quality; smaller particles (10 nm) yield superior films under low humidity, while larger particles (100 nm) perform better under high humidity, with PCEs up to 23.3%.

Lowering the temperature of organic cation precursor solutions slows down crystallization, leading to improved crystal orientation and 24.10% PCE. For carbon-based perovskite solar cells, Cu₂ZnGeS₄ nanocrystals as HTLs provide suitable band alignment and achieve 18.02% PCE. These approaches demonstrate the diversity of solvent and modulation strategies in advancing perovskite solar cell technology.

Outlook and Challenges

Despite significant progress, two-step spin-coated perovskite solar cells face challenges in bridging the efficiency gap with record-high devices and mitigating efficiency losses during scaling. The method often requires annealing in 30–40% humidity air, whose mechanism remains unclear. For commercialization, spin-coating is limited by scalability; thus, alternative methods like slot-die coating or evaporation-assisted two-step processes are being explored for large-area, high-quality films.

Future research should focus on understanding crystallization kinetics, developing novel additives, and optimizing interface engineering. The stability of perovskite solar cells under operational conditions, such as light, heat, and moisture, needs further improvement. Encapsulation techniques and stable charge transport materials are essential for long-term durability.

The efficiency of a perovskite solar cell is given by: $$\text{PCE} = \frac{J_{sc} \times V_{oc} \times \text{FF}}{P_{in}} \times 100\%$$ where $J_{sc}$ is the short-circuit current density, $V_{oc}$ is the open-circuit voltage, FF is the fill factor, and $P_{in}$ is the incident light power. Strategies that enhance these parameters through additive engineering, interface modification, and solvent optimization will drive the future development of high-performance perovskite solar cells.

In conclusion, the two-step spin-coating method offers a versatile platform for fabricating efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Continued innovation in material design and process engineering will pave the way for commercialization, enabling perovskite solar cells to contribute significantly to renewable energy solutions.