As a representative of third-generation photovoltaic technology, perovskite solar cells have garnered significant attention due to their rapid development in power conversion efficiency (PCE), which has increased from 3.8% to over 26.5% in just over a decade. Among various configurations, printable mesoscopic perovskite solar cells (p-MPSCs) stand out for their exceptional stability, attributed to the protective mesoporous structure and chemically inert carbon electrode. However, the substantial internal energy losses in these devices hinder further efficiency improvements. In this article, I explore the origins of energy loss in p-MPSCs, analyze carrier transport mechanisms, and evaluate strategies to overcome technical barriers from the perspectives of fabrication processes, additives, and solvents. The aim is to provide insights into the industrialization prospects of p-MPSCs, emphasizing the need for multidisciplinary approaches to address efficiency-stability-cost trade-offs.

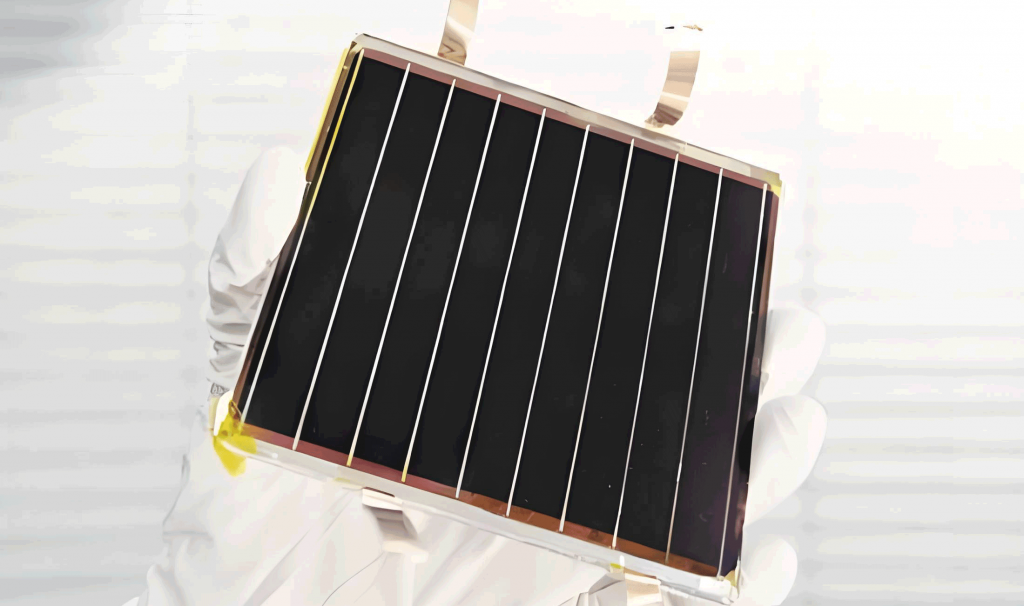

The unique architecture of p-MPSCs differs from conventional planar “sandwich” structures. From the light-incident side, the layers include a conductive glass substrate (e.g., FTO), a compact titanium dioxide (c-TiO₂) layer, a mesoporous titanium dioxide (m-TiO₂) layer, a mesoporous zirconium dioxide (m-ZrO₂) layer, and a mesoporous carbon (m-C) electrode. The perovskite film is deposited into these three mesoporous layers via solution-based methods. This design enhances stability by shielding the perovskite from environmental factors and leveraging the carbon electrode’s inertness. Nevertheless, the confined mesoporous structure often leads to poor perovskite film quality, resulting in inefficient carrier transport and increased energy loss. The primary challenge lies in optimizing perovskite crystallization within the mesopores to minimize non-radiative recombination and improve charge extraction.

Carrier transport in p-MPSCs is governed by the interactions between the perovskite and mesoporous layers. Upon photon absorption, electron-hole pairs are generated in the perovskite. Electrons are extracted by the m-TiO₂ layer and transported to the FTO electrode, while holes migrate through the perovskite in the m-ZrO₂ layer to the m-C electrode. The absence of a dedicated hole transport layer simplifies fabrication but introduces energy level mismatches and increased recombination at the perovskite-carbon interface. The energy loss in p-MPSCs can be quantified by the difference between the theoretical and actual PCE, often expressed as:

$$ \Delta E = E_{\text{theory}} – \text{PCE} $$

where \( E_{\text{theory}} \) represents the maximum achievable efficiency based on material bandgaps. Factors contributing to \( \Delta E \) include interface defects, inefficient charge separation, and resistive losses. For instance, the fill factor (FF) and open-circuit voltage (\( V_{oc} \)) are critical parameters affected by recombination, as shown in:

$$ V_{oc} = \frac{kT}{q} \ln\left( \frac{J_{sc}}{J_0} + 1 \right) $$

where \( J_{sc} \) is the short-circuit current density, \( J_0 \) is the reverse saturation current density, \( k \) is Boltzmann’s constant, \( T \) is temperature, and \( q \) is the electron charge. Reducing \( J_0 \) by minimizing recombination is essential for enhancing \( V_{oc} \) and overall PCE in perovskite solar cells.

Device Structure and Fabrication Processes

The fabrication of p-MPSCs primarily employs screen-printing techniques for the mesoporous layers, except for the c-TiO₂ layer, which is typically deposited via spray pyrolysis or chemical bath deposition. This process compatibility with large-scale manufacturing underscores the industrial potential of perovskite solar cells. The m-TiO₂ layer serves dual roles: as an electron transporter and a scaffold for perovskite crystallization. However, high-temperature sintering during fabrication introduces oxygen vacancies in m-TiO₂, which can either enhance conductivity or act as recombination centers depending on their concentration and distribution. Surface oxygen vacancies facilitate electron injection but may increase recombination if excessive, while bulk vacancies improve conductivity but reduce carrier mobility at high densities.

To manage oxygen vacancies, strategies like reduction-oxidation treatments have been developed. For example, a two-step method involves reducing m-TiO₂ to introduce oxygen vacancies, followed by oxidation to remove surface vacancies while retaining subsurface ones. This approach optimizes energy level alignment and reduces interface recombination. Additionally, post-treatment processes, such as molecular modifications, can induce p-type energy shifts in the perovskite and form n/n-type homojunctions at the carbon-perovskite interface, enhancing carrier separation. The table below summarizes key fabrication steps and their impacts on p-MPSC performance:

| Fabrication Step | Description | Impact on Perovskite Solar Cells |

|---|---|---|

| c-TiO₂ Deposition | Spray pyrolysis or chemical bath | Forms electron-selective layer, blocks holes |

| Mesoporous Layer Printing | Screen-printing of m-TiO₂, m-ZrO₂, m-C | Provides scaffold for perovskite, enables charge transport |

| Perovskite Infiltration | Solution deposition into mesopores | Determines film quality and carrier dynamics |

| Oxygen Vacancy Management | Reduction-oxidation treatments | Enhances conductivity, reduces recombination |

The carrier transport mechanism in p-MPSCs involves multiple pathways. Electrons extracted by m-TiO₂ must traverse the mesoporous network without recombining with holes. The effective electron mobility \( \mu_e \) in m-TiO₂ can be modeled using:

$$ \mu_e = \mu_0 \exp\left( -\frac{E_a}{kT} \right) $$

where \( \mu_0 \) is the intrinsic mobility and \( E_a \) is the activation energy. Similarly, hole transport through the perovskite in m-ZrO₂ to the carbon electrode is influenced by the perovskite’s crystallinity and interface properties. Optimizing these parameters is crucial for reducing energy loss in perovskite solar cells.

Additive Engineering for Performance Enhancement

Additives play a pivotal role in modulating perovskite crystallization and passivating defects in p-MPSCs. They can be categorized into volatile and non-volatile types based on their retention after annealing. Volatile additives, such as methylammonium chloride (MACl), evaporate during thermal processing and regulate crystallization kinetics. For instance, MACl facilitates the formation of intermediate phases that promote uniform perovskite film growth. In p-MPSCs, volatile additives like ammonium chloride (NH₄Cl) have been used to induce moisture-assisted nucleation, leading to highly oriented crystal structures and improved stability. The reaction kinetics can be described by:

$$ \frac{d[P]}{dt} = k [A]^n $$

where \( [P] \) is the perovskite concentration, \( [A] \) is the additive concentration, \( k \) is the rate constant, and \( n \) is the reaction order. This equation highlights how additives influence crystallization speed and phase purity.

Non-volatile additives, such as polymer networks or dipole molecules, remain in the film after processing and passivate defects. For example, N-aminocarbonyl-2-prop-2-ylpent-4-enamide forms a cross-linked polymer that anchors organic components via hydrogen bonding and coordination, suppressing ion migration and reducing defect densities. Dipole molecules with electron-donating groups optimize energy level alignment at the perovskite-carbon interface, enhancing hole extraction. The table below compares volatile and non-volatile additives:

| Additive Type | Examples | Mechanism | Impact on Perovskite Solar Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volatile | MACl, NH₄Cl, FACl | Forms intermediate phases, regulates crystallization | Improves film uniformity, reduces phase impurities |

| Non-volatile | Polymer networks, dipole molecules | Passivates defects, enhances interface properties | Increases stability, reduces recombination |

In p-MPSCs, additive selection must consider the mesoporous confinement. For instance, ionic liquids like methylammonium acetate (MAAc) prioritize interaction with PbI₂ to form intermediate complexes, leading to dense perovskite filling in the pores. The defect passivation efficacy can be quantified by the reduction in trap density \( N_t \), given by:

$$ N_t = N_0 \exp\left( -\frac{E_t}{kT} \right) $$

where \( N_0 \) is the initial trap density and \( E_t \) is the trap energy level. Additives that lower \( N_t \) contribute to higher \( V_{oc} \) and FF in perovskite solar cells.

Solvent Systems and Crystallization Dynamics

Solvent choice critically affects perovskite film quality in p-MPSCs by influencing precursor solvation, intermediate phase formation, and crystallization kinetics. Common solvents like N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) coordinate with Pb²⁺ ions due to their moderate donor numbers, forming solvated intermediates that dictate crystal growth. The donor number (DN) theory provides a framework for evaluating solvent coordination strength, with higher DN solvents like DMSO (DN = 29.8) forming more stable adducts. In mesoporous structures, solvent volatilization and confinement effects alter nucleation behavior, requiring precise control over solvent mixtures.

For example, binary solvent systems like DMF/DMSO leverage competitive coordination to achieve uniform films. DMSO’s high DN promotes stable intermediate phases, while DMF’s lower DN (26.6) facilitates faster evaporation. The crystallization rate \( R_c \) can be expressed as:

$$ R_c = A \exp\left( -\frac{\Delta G^*}{kT} \right) $$

where \( A \) is a pre-exponential factor and \( \Delta G^* \) is the activation energy for nucleation. Solvents that reduce \( \Delta G^* \) enable better pore filling in p-MPSCs. Moreover, green solvents are gaining traction for sustainable manufacturing. Based on the CHEM21 solvent selection guide, harmful solvents like DMF and N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) are discouraged, while recommended options include DMSO and acetonitrile (ACN). ACN’s high volatility and low DN allow for rapid crystallization control, making it suitable for air-processed p-MPSCs. The table below summarizes solvent properties:

| Solvent | Donor Number | Volatility | Suitability for Perovskite Solar Cells |

|---|---|---|---|

| DMF | 26.6 | Moderate | Limited due to toxicity |

| DMSO | 29.8 | Low | High, forms stable adducts |

| ACN | 14.1 | High | Good, enables fast crystallization |

| NMP | 27.3 | Low | Not recommended, hazardous |

Solvent engineering also addresses environmental concerns. For instance, DMSO/ACN mixtures have been used to fabricate FAPbI₃ films with high efficiency and stability. The solvent-perovskite interaction energy \( E_{\text{int}} \) can be approximated using:

$$ E_{\text{int}} = -\frac{C}{r^6} $$

where \( C \) is a constant and \( r \) is the distance between solvent molecules and perovskite precursors. Optimizing \( E_{\text{int}} \) through solvent blending reduces defect formation and enhances carrier lifetime in perovskite solar cells.

Conclusion and Industrial Outlook

In summary, printable mesoscopic perovskite solar cells offer a promising path toward commercialization due to their stability, low-cost fabrication, and scalability. However, energy losses stemming from inefficient carrier transport and interface recombination remain significant bottlenecks. Through advanced fabrication techniques, additive engineering, and solvent optimization, progress has been made in improving PCE and stability. For instance, oxygen vacancy management in m-TiO₂ and the use of volatile additives have demonstrated enhanced charge extraction, while green solvents align with sustainability goals.

Future research should focus on elucidating the relationship between mesoporous filling and carrier transport dynamics using quantitative models. Multifunctional additives that simultaneously regulate crystallization, passivate defects, and inhibit ion migration could further boost performance. Additionally, developing solvent systems with optimal coordination strength and low toxicity will be crucial for large-scale production. The industrialization of p-MPSCs hinges on balancing efficiency, stability, and cost—a challenge that requires interdisciplinary efforts in materials science and process engineering. By addressing these aspects, p-MPSCs can overcome current limitations and contribute to the global adoption of perovskite solar cell technology.

The continued advancement of perovskite solar cells, particularly p-MPSCs, relies on innovative strategies to minimize energy loss and enhance durability. As I have discussed, understanding carrier mechanisms and optimizing material interactions are key to unlocking their full potential. With ongoing research, p-MPSCs may soon achieve the trifecta of high efficiency, long-term stability, and commercial viability, paving the way for a sustainable energy future.