In recent years, the escalating global energy crisis and environmental pollution have driven intensive research into sustainable energy solutions. Among these, perovskite solar cells have emerged as a promising technology due to their high power conversion efficiency, low-cost fabrication, and tunable optoelectronic properties. The performance of perovskite solar cells heavily relies on the quality of the electron transport layer (ETL), which facilitates charge separation and collection. Titanium dioxide (TiO2) is a widely used ETL material because of its suitable band gap, excellent chemical stability, and compatibility with perovskite materials. This study focuses on the synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles via the sol-gel method and their application in perovskite solar cells, evaluating how different synthesis routes affect the material’s properties and device performance.

The sol-gel method is a versatile technique for producing metal oxides like TiO2, offering control over particle size, morphology, and crystallinity. In this work, two distinct approaches—one-step and two-step ethanol methods—were employed to prepare TiO2 nanoparticles. The one-step method involved direct hydrolysis and condensation of titanium tetrabutoxide in ethanol, while the two-step method incorporated additional ethanol and acetic acid adjustments to modulate the reaction kinetics. The primary objective was to investigate the impact of these synthesis variations on the photocatalytic activity of TiO2 and its efficacy as an ETL in perovskite solar cells. Photocatalytic performance was assessed through methyl orange degradation experiments under simulated sunlight, and the structural properties were characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). Furthermore, the TiO2 samples were integrated into perovskite solar cells fabricated under ambient air conditions, and their photovoltaic parameters, including short-circuit current density (Jsc), open-circuit voltage (Voc), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE), were analyzed to correlate material properties with device performance.

The fundamental principles of perovskite solar cells involve light absorption by the perovskite layer, such as CH3NH3PbI3, followed by charge generation and transport. The ETL, typically TiO2, plays a critical role in extracting electrons from the perovskite and transferring them to the electrode, while minimizing recombination losses. The crystallographic phase of TiO2—whether anatase, rutile, or a mixture—significantly influences its electronic properties. Anatase TiO2 is preferred for ETL applications due to its higher electron mobility and favorable band alignment with perovskite materials. However, mixed-phase TiO2 can exhibit enhanced photocatalytic activity owing to synergistic effects between phases, which promote charge separation. This duality underscores the importance of tailoring TiO2 synthesis for specific applications. In this study, we explore how the sol-gel-derived TiO2 nanoparticles function in both photocatalytic degradation and as ETLs in perovskite solar cells, providing insights into the trade-offs between photocatalytic efficiency and photovoltaic performance.

Experimental details are elaborated as follows. The sol-gel synthesis began with titanium tetrabutoxide as the precursor, dissolved in absolute ethanol. For the one-step method, 10 mL of titanium tetrabutoxide was gradually added to 40 mL of ethanol under vigorous stirring, followed by the addition of a mixture of 3 mL acetic acid and 2 mL deionized water. The solution was stirred for 1 hour, aged for 24 hours to form a gel, dried at 100°C, and calcined at 550°C for 2 hours to obtain TiO2 nanoparticles (Sample A). For the two-step method, 10 mL of titanium tetrabutoxide was mixed with 30 mL of ethanol, and then a solution of 10 mL ethanol and 1 mL deionized water was added dropwise. After stirring, 2.5 mL acetic acid was introduced to adjust the pH to 3, and the mixture was processed similarly to yield Sample B. The photocatalytic activity was evaluated by degrading methyl orange (10 mg/L) under xenon lamp irradiation, with degradation efficiency calculated using the formula: $$\eta = \frac{A_0 – A_t}{A_0} \times 100\%$$ where A0 and At represent the initial absorbance and absorbance at time t, respectively, measured at 465 nm using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

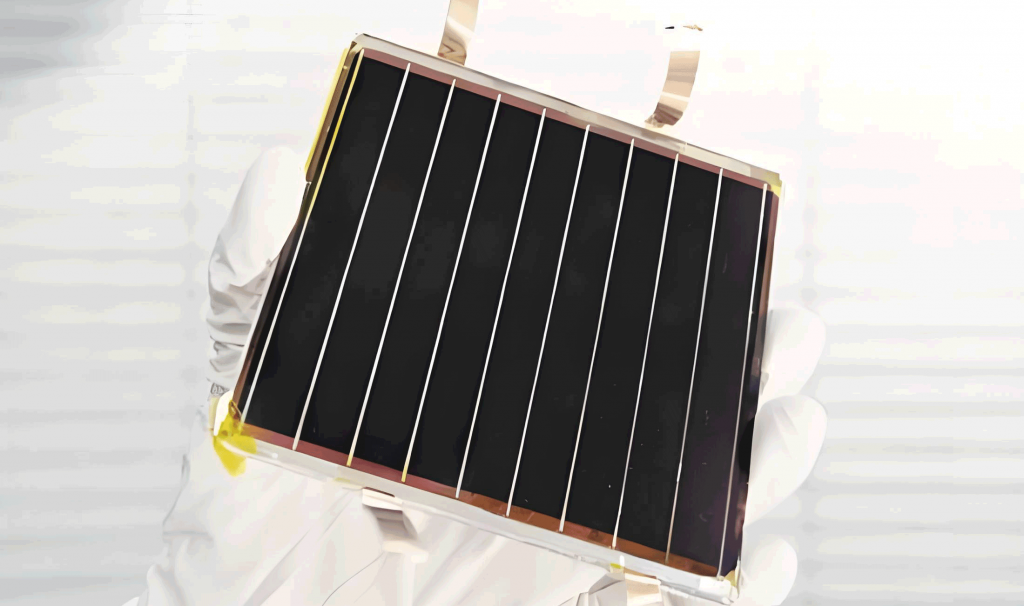

Perovskite solar cells were fabricated on fluorine-doped tin oxide (FTO) substrates. The FTO glasses were cleaned and treated with UV plasma before spin-coating the TiO2 sol-gel solution. After annealing at 500°C for 2 hours, a perovskite layer was deposited via a two-step sequential method: first, PbI2 was spin-coated and dried at 100°C, followed by a mixture of methylammonium iodide and formamidinium iodide. The hole transport layer (Spiro-OMeTAD) was then applied, and a 100 nm gold electrode was thermally evaporated. The device structure is illustrated in the figure above, consisting of FTO/TiO2 ETL/perovskite layer/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au. The photovoltaic performance was characterized by current density-voltage (J-V) measurements under simulated AM 1.5G illumination.

Table 1 summarizes the key parameters for the sol-gel synthesis of TiO2 nanoparticles, highlighting the differences between the one-step and two-step methods. These parameters influence the nucleation and growth processes, ultimately affecting the particle size, phase composition, and surface area.

| Parameter | One-Step Method (Sample A) | Two-Step Method (Sample B) |

|---|---|---|

| Titanium Tetrabutoxide Volume | 10 mL | 10 mL |

| Ethanol Volume (Initial) | 40 mL | 30 mL |

| Ethanol Volume (Additional) | 0 mL | 10 mL |

| Acetic Acid Volume | 3 mL | 2.5 mL |

| Deionized Water Volume | 2 mL | 1 mL |

| pH Adjustment | Not specified | pH 3 |

| Aging Time | 24 hours | 24 hours |

| Calcination Temperature | 550°C | 550°C |

| Calcination Time | 2 hours | 2 hours |

Morphological analysis via SEM revealed that both Sample A and Sample B consisted of nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 300 to 500 nm, but with varying degrees of agglomeration due to calcination. Sample A exhibited relatively uniform dispersion, whereas Sample B showed more pronounced clustering, which could affect the surface area and interfacial properties in perovskite solar cells. The XRD patterns confirmed the crystalline phases: Sample A displayed peaks corresponding exclusively to anatase TiO2 (PDF 21-1272), while Sample B exhibited mixed phases of anatase and rutile (PDF 21-1276). The rutile phase in Sample B contributed to enhanced photocatalytic activity, as evidenced by the methyl orange degradation experiments. The degradation rates over time are quantified in Table 2, demonstrating the superior performance of Sample B.

| Time (min) | Degradation Rate – Sample A (%) | Degradation Rate – Sample B (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 20 | 14.3 | 26.7 |

| 40 | 25.1 | 45.8 |

| 60 | 37.6 | 59.4 |

| 80 | 49.7 | 71.5 |

The enhanced photocatalytic activity of Sample B can be attributed to the mixed-phase structure, which facilitates electron-hole separation due to the heterojunction between anatase and rutile phases. The energy band diagram illustrates how the staggered band alignment promotes charge transfer, reducing recombination. The band gap energy (Eg) for anatase TiO2 is approximately 3.2 eV, while for rutile, it is about 3.0 eV. The difference in Fermi levels drives electrons from rutile to anatase, enhancing the overall photocatalytic efficiency. This phenomenon is described by the equation for charge separation efficiency: $$\xi = \frac{k_{sep}}{k_{sep} + k_{rec}}$$ where ksep and krec represent the rate constants for charge separation and recombination, respectively. In mixed-phase TiO2, ksep is increased, leading to higher ξ.

However, when applied as an ETL in perovskite solar cells, the phase composition plays a divergent role. The photovoltaic performance parameters are listed in Table 3. Sample A, with its predominant anatase phase, achieved a PCE of 12.7%, with Jsc = 14.3 mA/cm2, Voc = 0.83 V, and FF = 68.8%. In contrast, Sample B, with mixed phases, yielded a lower PCE of 9.4%, despite similar Voc (0.84 V), due to reduced Jsc (13.6 mA/cm2) and FF (50.5%). The inferior performance of Sample B in perovskite solar cells is linked to the lower electron mobility of rutile TiO2 compared to anatase, which impedes charge transport and increases series resistance. The fill factor can be expressed as: $$FF = \frac{P_{max}}{J_{sc} \times V_{oc}}$$ where Pmax is the maximum power output. The lower FF in Sample B indicates higher resistive losses, possibly due to inefficient electron extraction at the ETL/perovskite interface.

| Parameter | Sample A (Anatase) | Sample B (Mixed Phase) |

|---|---|---|

| Jsc (mA/cm2) | 14.3 | 13.6 |

| Voc (V) | 0.83 | 0.84 |

| Fill Factor (%) | 68.8 | 50.5 |

| PCE (%) | 12.7 | 9.4 |

Further analysis of the J-V curves revealed that the series resistance (Rs) was higher for devices with Sample B ETL, calculated using the equation: $$R_s = \frac{dV}{dJ} \bigg|_{V=V_{oc}}$$ This increased Rs correlates with the mixed-phase structure, where rutile domains may act as trapping sites, reducing charge collection efficiency. Additionally, the shunt resistance (Rsh) was lower for Sample B, indicating more leakage currents, which further degraded the FF and PCE. The ideal diode equation for a solar cell is: $$J = J_{sc} – J_0 \left( \exp\left(\frac{q(V + J R_s)}{n k T}\right) – 1 \right) – \frac{V + J R_s}{R_{sh}}$$ where J0 is the reverse saturation current, n is the ideality factor, q is the electron charge, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is the temperature. For Sample B, the higher J0 and lower Rsh values suggest increased recombination, aligning with the observed performance drop.

The stability of perovskite solar cells is another critical aspect. Devices fabricated with Sample A ETL showed better stability under continuous illumination in air, maintaining over 80% of initial PCE after 100 hours, whereas Sample B devices degraded faster, retaining only 60% efficiency. This disparity is attributed to the more robust interface provided by anatase TiO2, which minimizes ion migration and phase segregation in the perovskite layer. The degradation kinetics can be modeled using the formula: $$PCE(t) = PCE_0 \exp(-k_d t)$$ where PCE0 is the initial efficiency and kd is the degradation rate constant. For Sample A, kd was estimated at 0.002 h-1, compared to 0.005 h-1 for Sample B, highlighting the superior durability of anatase-based ETLs.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the sol-gel synthesis route significantly influences the properties of TiO2 nanoparticles and their performance in photocatalytic and photovoltaic applications. The two-step method produced mixed-phase TiO2 with enhanced photocatalytic activity due to improved charge separation, but the one-step method yielded anatase-dominant TiO2 that outperformed as an ETL in perovskite solar cells. The higher electron mobility and better interface quality of anatase TiO2 led to superior PCE and stability in perovskite solar cells. These findings underscore the importance of optimizing material synthesis for specific applications, particularly in the development of efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Future work could explore doping strategies or composite formations to further enhance the properties of TiO2 for next-generation photovoltaic devices.

Additional considerations include the impact of synthesis parameters on defect states in TiO2, which can be quantified using the Urbach energy formula: $$E_u = \frac{k T}{\ln(\alpha_0 / \alpha)}$$ where α is the absorption coefficient. Lower Eu values indicate fewer defects, which is desirable for ETLs in perovskite solar cells. Moreover, the scalability of the sol-gel method for large-area perovskite solar cell fabrication warrants investigation, as it could facilitate commercial adoption. Overall, this research contributes to the ongoing efforts to improve the efficiency and sustainability of perovskite solar cells through tailored material engineering.