The pressing global imperative for energy transition and carbon emission reduction has fundamentally reshaped industrial operational paradigms. As a significant sector within the manufacturing industry, printing enterprises traditionally exhibit characteristics such as singular energy supply modes, poor flexibility, and uncontrollable carbon footprints. To address these challenges and align with national “dual-carbon” strategic goals, the transformation towards an Integrated Energy System (IES) has emerged as a critical development path. An IES synergistically combines various energy inputs, conversion technologies, and storage solutions to enhance overall efficiency, reliability, and sustainability. Within this framework, the integration of renewable energy sources like wind and photovoltaic (PV) generation is paramount for decarbonization. However, their inherent intermittency and volatility necessitate the incorporation of energy storage to ensure grid stability and maximize utilization. Among storage technologies, the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) plays a pivotal role due to its rapid response and scalability.

My research focuses on the intricate optimization of IES operations specifically for printing enterprises, with a particular emphasis on accurately modeling and mitigating the life degradation of the battery energy storage system. A critical oversight in many existing operational models is the treatment of the BESS as a static asset with fixed operational costs, neglecting the profound impact that charge-discharge strategies have on its longevity. Frequent cycling, especially at high depths of discharge, accelerates capacity fade and increases the long-term economic burden due to premature replacement. Therefore, developing an optimization strategy that internalizes the cost of battery degradation is essential for achieving truly economical and sustainable operation.

This article presents a holistic methodology encompassing the construction of a detailed IES model for a printing enterprise, the formulation of a physics-informed battery lifetime degradation model, the establishment of a multi-objective optimization framework, and the proposal of an enhanced solving algorithm. The core objective is to devise an operational strategy that minimizes total cost—comprising energy procurement, equipment maintenance, environmental penalties, and battery energy storage system degradation—while satisfying all operational constraints.

1. Architecture and Mathematical Modeling of the Printing Enterprise IES

The proposed Integrated Energy System is designed to meet the specific load profile of a printing facility, which often involves high and fluctuating power demands from printing presses, dryers, and auxiliary equipment. The system’s architecture integrates multiple energy carriers and conversion technologies to ensure reliability and efficiency.

1.1 System Framework and Energy Flow

The IES is structured into three primary layers: the Energy Input Layer, the Energy Conversion Layer, and the Energy Output Layer. The input layer includes the main power grid, the natural gas grid, and local renewable sources (wind and solar). The conversion layer comprises devices that transform these input energies into usable forms: Microturbines (MT) convert natural gas to electricity and heat, while Wind Turbines (WT) and Photovoltaic (PV) panels convert renewable resources into electricity. The output layer serves the electrical loads of the printing facility and includes the battery energy storage system for energy shifting and grid support. The interconnection allows for versatile energy flows; for instance, excess renewable generation can charge the BESS, supply the load, or be sold to the grid, while the MT and grid can supplement supply when renewables are insufficient.

1.2 Modeling of Conversion and Generation Units

Each component within the IES is modeled with its operational characteristics and costs.

Microturbine (MT): The MT’s efficiency ($\eta_{MT}$) is a non-linear function of its output power ($P_{MT}$), significantly affecting its fuel consumption.

$$ \eta_{MT} = a_2 \cdot \left(\frac{P_{MT}}{65}\right)^3 – b_2 \cdot \left(\frac{P_{MT}}{65}\right)^2 + c_2 \cdot \left(\frac{P_{MT}}{65}\right) + d_2 $$

Its operational cost includes fuel cost ($C_{MTF}$), operation & maintenance (O&M) cost ($C_{MTOM}$), and emission treatment cost ($C_{MTEN}$).

$$ C_{MTF} = \frac{C_{gas} \cdot P_{MT} \cdot \Delta t}{LHV \cdot \eta_{MT}}, \quad C_{MTOM} = K_{MTOM} \cdot P_{MT}, \quad C_{MTEN} = \sum_{k=1}^{n} (C_{k} \cdot \chi_k \cdot P_{MT}) $$

Here, $C_{gas}$ is natural gas price, $LHV$ is its lower heating value, $K_{MTOM}$ is the O&M coefficient, $C_k$ is the treatment cost for pollutant $k$ (e.g., CO₂, SO₂, NOx), and $\chi_k$ is the corresponding emission factor.

Diesel Generator (DE): Used for backup and peak shaving, its fuel cost is typically a quadratic function of output power ($P_{DE}$).

$$ C_{DEF} = a_1 \cdot P_{DE}^2 + b_1 \cdot P_{DE} + c_1 $$

Its O&M ($C_{DEOM}$) and emission costs ($C_{DEEN}$) are modeled similarly to the MT.

$$ C_{DEOM} = K_{DEOM} \cdot P_{DE}, \quad C_{DEEN} = \sum_{k=1}^{n} (C_{k} \cdot \delta_k \cdot P_{DE}) $$

Renewable Generators (PV & WT): Their output ($P_{PV}(t)$, $P_{WT}(t)$) is considered a forecasted input based on weather data. Their O&M costs are often simplified or included in the initial investment.

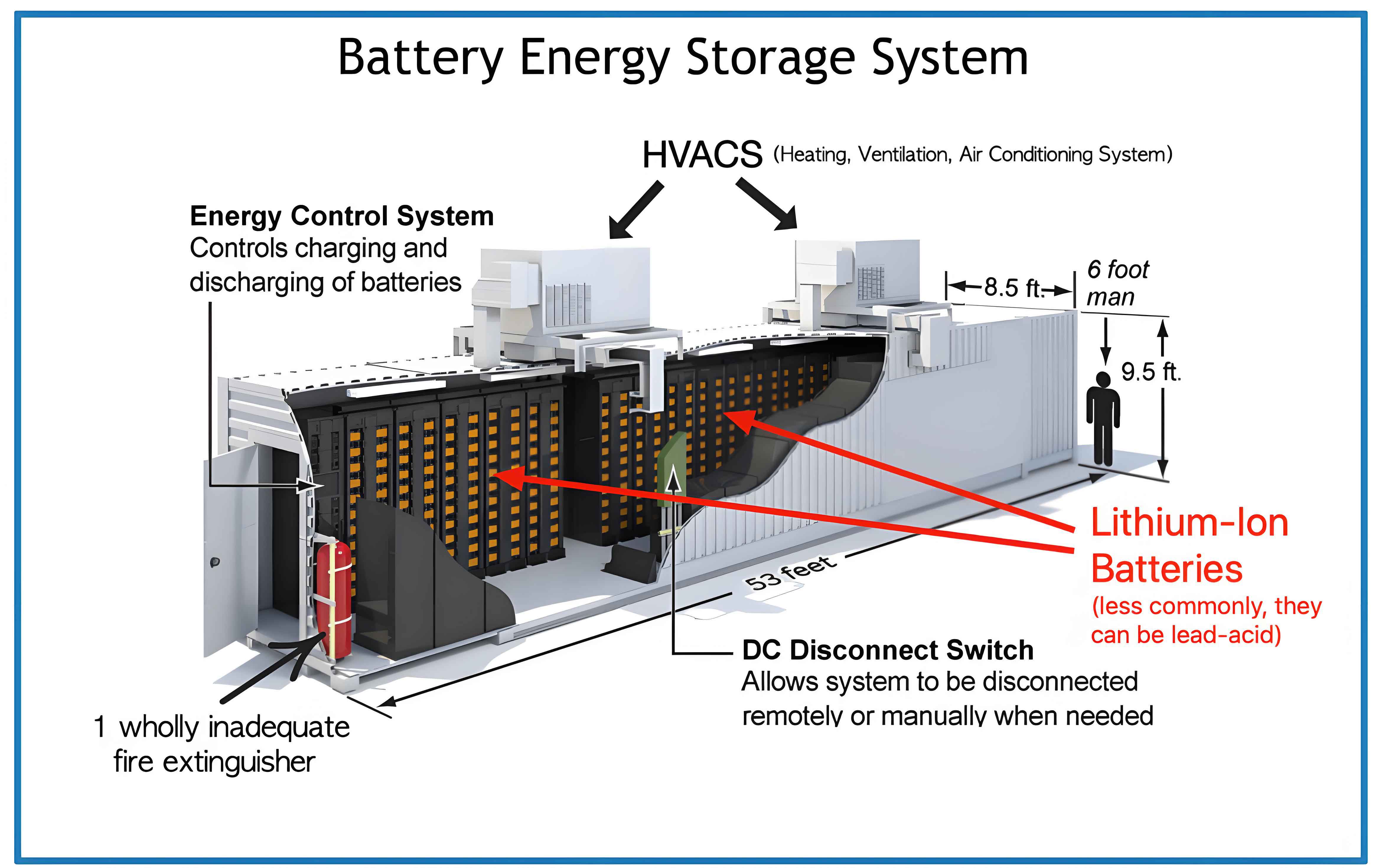

1.3 Modeling the Battery Energy Storage System (BESS)

The battery energy storage system is a dynamic component. Its state of charge (SOC) evolution is governed by:

$$ SOC(t) = SOC(t-1) + \left( \frac{\eta_{ch} \cdot P_{ch}(t) \cdot \Delta t}{E_{B}} – \frac{P_{dis}(t) \cdot \Delta t}{\eta_{dis} \cdot E_{B}} \right) $$

where $P_{ch}(t), P_{dis}(t) \ge 0$ are charge and discharge powers, $\eta_{ch}, \eta_{dis}$ are efficiencies, $E_B$ is the rated capacity, and $\Delta t$ is the time interval. The SOC must be maintained within safe limits: $SOC_{min} \le SOC(t) \le SOC_{max}$.

1.3.1 Battery Lifetime Degradation Model

The core innovation lies in integrating a cycle-life degradation model for the BESS, typically based on Lithium Iron Phosphate (LiFePO₄) chemistry. The cycle life ($N$) is highly dependent on the Depth of Discharge (DOD). Experimental data can be fitted to a polynomial function. A 5th-order polynomial provides a good fit:

$$ N(DOD) = -1302 \cdot DOD^5 + 4427 \cdot DOD^3 – 8925 \cdot DOD^2 + 10500 $$

where $DOD = 1 – SOC_{min}$ for a given cycle identified from the SOC profile using the rainflow counting algorithm. The State of Health (SOH) represents the remaining capacity fraction, and battery end-of-life is typically defined as $SOH = 0.8$.

The daily capacity degradation ($\gamma_{BESS}$) is calculated by summing the impact of all cycles identified in a day:

$$ \gamma_{BESS} = \sum_{i=1}^{n_{cycles}} \frac{1}{N(DOD_i)} $$

The remaining life in days ($\varepsilon$) is then: $\varepsilon = 1 / \gamma_{BESS}$ (for daily repeated profiles). The associated daily degradation cost ($C_{deg}$) is derived by amortizing the capital cost ($C_{bin}$) over the projected life, using the capital recovery factor:

$$ C_{deg} = \frac{C_{bin} \cdot r \cdot (1+r)^{T_{cal}}}{(1+r)^{T_{cal}}-1} \cdot \frac{1}{365} + C_{bw} $$

where $r$ is the discount rate, $T_{cal}$ is the projected life in years ($\varepsilon/365$), and $C_{bw}$ is the annual maintenance cost.

1.4 System Constraints

The operation must satisfy the following key constraints:

Power Balance Constraint:

$$ P_{PV}(t) + P_{WT}(t) + P_{Grid}(t) + P_{MT}(t) + P_{DE}(t) + P_{dis}(t) – P_{ch}(t) = P_{Load}(t) $$

Device Output Limits:

$$ P_{i,min} \le P_i(t) \le P_{i,max} \quad \text{for } i \in \{MT, DE, BESS, Grid\} $$

Ramp Rate Limits:

$$ |P_i(t) – P_i(t-1)| \le \Delta P_{i, max} \cdot \Delta t \quad \text{for } i \in \{MT, DE\} $$

2. Multi-Objective Optimization Formulation

The optimal dispatch of the IES is formulated as a multi-objective problem, seeking to minimize conflicting goals simultaneously.

2.1 Objective Functions

Objective 1: Total Operational Cost ($F_1$)

This includes energy exchange costs, fuel costs, O&M costs, and the degradation cost of the battery energy storage system.

$$ F_1 = C_{Grid} + C_{MT} + C_{DE} + C_{BESS} $$

$$ C_{Grid} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \left( c_{buy}(t) \cdot P_{buy}(t) – c_{sell}(t) \cdot P_{sell}(t) \right) \Delta t $$

$$ C_{MT} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} (C_{MTF}(t) + C_{MTOM}(t)) \Delta t $$

$$ C_{DE} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} (C_{DEF}(t) + C_{DEOM}(t)) \Delta t $$

$$ C_{BESS} = C_{deg} + \sum_{t=1}^{T} K_{BESS} \cdot (P_{ch}(t)+P_{dis}(t)) \Delta t $$

Objective 2: Environmental Cost ($F_2$)

This quantifies the penalty for pollutant emissions from all generation sources, including the grid (with grid emission factors $\sigma_k$).

$$ F_2 = C_{GridEN} + C_{MTEN} + C_{DEEN} $$

$$ C_{GridEN} = \sum_{t=1}^{T} \sum_{k=1}^{n} (C_{k} \cdot \sigma_k \cdot P_{buy}(t)) \Delta t $$

In essence, the optimization problem is: $\min \mathbf{F} = [F_1, F_2]^T$, subject to the system constraints outlined in Section 1.4.

3. Solution Algorithm: Chaos Mutation Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (CM-MOPSO)

Solving the described non-linear, constrained, multi-objective problem requires a robust algorithm. While standard Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) is effective, it can suffer from premature convergence. I propose an enhanced CM-MOPSO algorithm with the following improvements:

3.1 Chaotic Initialization

To ensure a more uniform and diverse initial population spread across the search space, a cubic map chaotic sequence is used instead of random initialization.

$$ y_{n+1} = 4y_n^3 – 3y_n, \quad y_0 \in (-1,1), y_0 \ne 0 $$

The chaotic sequence is then mapped to the solution variable bounds $[L_d, U_d]$:

$$ x_d = L_d + \frac{U_d – L_d}{2} (1 + y) $$

3.2 Dynamic Inertia Weight

A linearly decreasing inertia weight ($w$) balances global exploration and local exploitation.

$$ w(i) = w_{end} + \frac{(w_{start} – w_{end})(i_{max} – i)}{i_{max}} $$

where $i$ is the current iteration, $i_{max}$ is the maximum iteration, $w_{start}$ and $w_{end}$ are initial and final weights.

3.3 Mutation Strategy with Adaptive Probability

To escape local Pareto fronts, a mutation operator with adaptive probability ($P_m$) is introduced. The probability decreases as the search progresses.

$$ P_m(i) = 1 – \left(\frac{i-1}{i_{max}-1}\right)^\mu $$

where $\mu$ controls the decay rate. A particle’s velocity or position is perturbed with probability $P_m(i)$.

3.4 Algorithm Framework

The CM-MOPSO algorithm integrates the above features within a standard MOPSO structure that uses an external archive to store non-dominated solutions and a grid-based approach for selecting the global guide. The velocity and position update for particle $n$ in dimension $d$ is:

$$ v_{nd}^{k+1} = w \cdot v_{nd}^{k} + \tau_1 \cdot \xi_1 \cdot (M_{pd}^{k} – x_{nd}^{k}) + \tau_2 \cdot \xi_2 \cdot (M_{gd}^{k} – x_{nd}^{k}) $$

$$ x_{nd}^{k+1} = x_{nd}^{k} + v_{nd}^{k+1} $$

where $M_p$ and $M_g$ are the personal and global best positions, $\tau_1, \tau_2$ are learning factors, and $\xi_1, \xi_2$ are random numbers.

4. Case Study and Simulation Results

A case study based on a printing enterprise in China was conducted over a 24-hour period. Forecast data for PV, WT, and electrical load were used as inputs.

4.1 System Parameters and Scenarios

Key parameters for the IES components and cost coefficients are summarized below.

| Component | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Microturbine (MT) | $P_{min} / P_{max}$ (kW) | 3 / 30 |

| Ramp Limit (kW/h) | 1.5 | |

| O&M Cost Coeff. ($K_{MTOM}$) ($/kWh) | 0.0293 | |

| Efficiency Params ($a_2, b_2, c_2, d_2$) | -0.9, 3.5, -3.6, 0.9 | |

| Diesel Gen. (DE) | $P_{min} / P_{max}$ (kW) | 6 / 30 |

| O&M Cost Coeff. ($K_{DEOM}$) ($/kWh) | 0.128 | |

| Fuel Cost Params ($a_1, b_1, c_1$) | 0.08, 0.24, 0 | |

| Battery (LiFePO₄) | Rated Capacity $E_B$ (kWh) | 150 |

| $P_{ch,max} / P_{dis,max}$ (kW) | 30 / 30 | |

| Ch/Dis Efficiency ($\eta_{ch}, \eta_{dis}$) | 0.9 / 0.9 | |

| $SOC_{min} / SOC_{max}$ | 0.2 / 0.9 | |

| Capital Cost $C_{bin}$ ($) | 45,000 | |

| Annual Maint. Cost $C_{bw}$ ($) | 500 | |

| Grid | Buy/Sell Price ($/kWh) – Peak/Flat/Valley | 1.35/0.82/0.38 / 0.36 |

Two main operational scenarios were defined for comparison:

- Scenario 1 (Proposed): IES optimization WITH the integrated battery energy storage system degradation model and cost.

- Scenario 2 (Conventional): IES optimization WITHOUT the degradation model, treating BESS O&M as a simple linear cost.

Both scenarios were solved using the standard MOPSO and the proposed CM-MOPSO to evaluate algorithmic performance.

4.2 Algorithm Performance Comparison

The table below compares the average performance of MOPSO and CM-MOPSO over 100 runs for Scenario 1, demonstrating the superiority of the enhanced algorithm.

| Performance Metric | Standard MOPSO | Proposed CM-MOPSO | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Computation Time (s) | 397 | 355 | ~10.6% faster |

| Best Found Total Cost F1 ($) | 423.61 | 406.33 | ~4.1% lower |

| (Components: Op. Cost / Env. Cost) | (364.67 / 58.94) | (352.70 / 53.63) |

CM-MOPSO’s chaotic initialization and mutation strategy led to better exploration of the solution space, resulting in a lower-cost Pareto-optimal solution and faster convergence.

4.3 Impact of the Battery Degradation Model

The most significant findings relate to the comparison between Scenario 1 and Scenario 2 when solved with the superior CM-MOPSO algorithm.

| Cost Component ($) | Scenario 2 (No Degradation Model) | Scenario 1 (With Degradation Model) | Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| BESS Degradation Cost ($C_{deg}$) | 22.87* | 22.87 | Explicitly accounted for in F1 |

| Operational Cost (Grid, Fuel, O&M) | 349.35 | 352.70 | Slightly higher in Scenario 1 |

| Environmental Cost ($F_2$) | 52.88 | 53.63 | Comparable |

| Total Daily Cost ($F_1$) | 425.10 | 406.33 | Scenario 1 is ~4.4% cheaper |

*In Scenario 2, this is a fixed linear O&M cost, not a true degradation cost.

The key insight is that while operational costs are marginally higher in Scenario 1, the overall daily cost is lower. This is because the optimization in Scenario 1 intelligently manages the battery energy storage system to reduce long-term degradation, effectively lowering the amortized daily capital cost. The BESS dispatch strategy changes significantly:

- In Scenario 2, without degradation concerns, the BESS is used aggressively for price arbitrage, leading to deep and frequent cycles. The SOC swings widely (e.g., from 0.31 to 0.64).

- In Scenario 1, the optimizer trades off some short-term arbitrage gain to protect the battery. The SOC is maintained in a narrower, shallower band (e.g., from 0.38 to 0.47), significantly reducing stress.

4.4 Battery Lifetime Extension Analysis

The long-term benefit is quantified by projecting battery life. Using the rainflow analysis on the daily SOC profile from each scenario:

- Scenario 2 Profile: Projected battery life ≈ 7,737 days.

- Scenario 1 Profile: Projected battery life ≈ 9,199 days.

This represents a ~15.9% extension in usable battery life solely by employing the degradation-aware operational strategy. This directly translates to reduced replacement frequency and lower long-term costs for the battery energy storage system, validating the core premise of this research.

5. Conclusion

This research has successfully developed and demonstrated a comprehensive framework for optimizing the operation of an Integrated Energy System tailored for printing enterprises. The principal contribution lies in the explicit integration of a physics-based, cycle-life degradation model for the Lithium Iron Phosphate battery energy storage system into the economic dispatch formulation. By internalizing the long-term cost of battery wear, the optimization strategy naturally evolves towards a more sustainable and ultimately more economical operating regime for the BESS.

The proposed Chaos Mutation Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (CM-MOPSO) algorithm proved effective in solving the complex, constrained multi-objective problem, outperforming the standard MOPSO in both solution quality and computational efficiency. Simulation results from a realistic case study compellingly show that while a degradation-agnostic strategy might seem optimal in the very short term, it incurs hidden high costs through accelerated battery aging. In contrast, the proposed method reduces the daily amortized cost of the battery energy storage system by promoting shallower charge-discharge cycles, extending the projected battery lifespan by approximately 15.9%. This leads to a lower total daily operational cost when degradation is properly accounted for.

Therefore, for printing enterprises and similar industrial facilities investing in integrated energy systems with storage, adopting an operational philosophy that values and protects the longevity of the battery energy storage system is not merely an environmental consideration but a sound economic decision. This methodology provides a practical tool to achieve that balance, facilitating the transition towards more resilient, efficient, and low-carbon industrial energy systems.