In recent years, organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells have emerged as a transformative technology in the photovoltaic sector due to their exceptional properties, including high photon-to-electron conversion efficiency potential, low fabrication costs, tandem capability, and flexibility. Since their introduction in 2009, perovskite solar cells have achieved a certified efficiency of 27.0%, surpassing traditional solar cells like copper indium gallium selenide and cadmium telluride. However, the industrialization of perovskite solar cells faces significant challenges, such as efficiency degradation in large-area devices and insufficient long-term stability under environmental stressors like humidity, oxygen, heat, and light. This review comprehensively examines the progress in large-area fabrication techniques, flexible perovskite solar cells, perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells, and stability enhancement strategies, aiming to provide insights for the commercial development of perovskite solar cell technology.

The core material of perovskite solar cells is the organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite, which has a general formula of ABX3, where A represents monovalent organic cations like methylammonium or formamidinium, B is a divalent metal ion such as Pb2+ or Sn2+, and X denotes halide ions like I−, Br−, or Cl−. This structure contributes to high absorption coefficients, long carrier lifetimes, tunable bandgaps, and solution processability, making perovskite solar cells ideal for various applications. Despite the exploration of all-inorganic perovskites, their efficiencies remain lower than hybrid systems. The rapid improvement in perovskite solar cell efficiency from 3.8% to 27.0% has been driven by optimizations in device architecture, perovskite composition, and interfacial engineering. Nevertheless, scaling up perovskite solar cells to practical sizes (e.g., over 150 cm²) results in notable efficiency losses due to issues like carrier transport limitations, film non-uniformity, and interfacial defects. In this review, we delve into the key aspects of perovskite solar cell industrialization, focusing on fabrication methods, flexible and tandem configurations, and stability solutions.

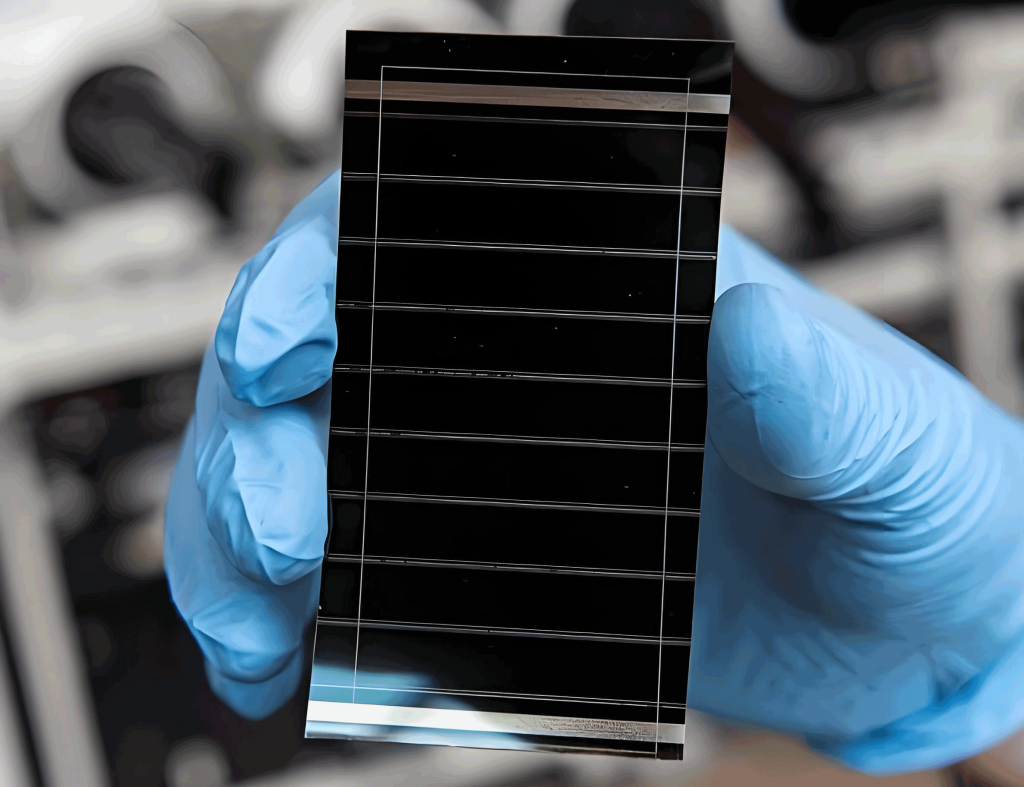

Perovskite Thin Film Fabrication Methods

The fabrication of high-quality perovskite thin films is critical for the performance of perovskite solar cells, especially as device area increases. Efficiency typically decreases by approximately 1.5% per order of magnitude increase in area, primarily due to extended carrier transport distances, film defects like pinholes and thickness variations, and interfacial issues. To address these challenges, various deposition techniques have been developed, each with unique advantages and limitations for industrial scalability.

Spin-Coating

Spin-coating is widely used in laboratories for small-area perovskite solar cells (less than 100 cm²) due to its simplicity, reproducibility, and ease of operation. This method relies on centrifugal force to distribute the precursor solution evenly across a substrate, controlling film thickness. By optimizing parameters such as solvent ratios, precursor composition, and spin speed, researchers have achieved improved film quality. For instance, early studies demonstrated perovskite solar modules with efficiencies of 5.1% on 17 cm² areas and 8.7% on 60 cm² areas using spin-coating. However, the centrifugal force varies with radius, leading to thickness and performance inconsistencies across the film, which limits its applicability to large-scale industrial production of perovskite solar cells.

Blade-Coating

Blade-coating involves the relative motion between a blade and substrate to uniformly coat the precursor solution, forming a wet film with controllable thickness. It is a scalable and straightforward method for perovskite solar cell fabrication. Adjusting parameters like coating speed, blade height, and substrate temperature can influence nucleation and crystallization, thereby tuning film thickness. However, blade-coated films are often thick with slow solvent evaporation, potentially affecting perovskite crystallization. Assisted by substrate heating, nitrogen blowing, or vacuum flash evaporation, this method has been enhanced; for example, incorporating surfactants like L-α-phosphatidylcholine improved film uniformity. Despite these advances, blade-coating generally results in lower efficiencies for perovskite solar cells, and its industrial impact remains limited due to challenges in thickness control and uniformity.

Slot-Die Coating

Slot-die coating shares similarities with blade-coating but employs a unique coating head design that forms a coating bead between the head and substrate, enabling precise control over film thickness and uniformity. Parameters such as precursor concentration, head-to-substrate distance, and coating speed can be optimized, often with辅助 techniques like nitrogen blowing, vacuum drying, or substrate heating to accelerate solvent removal and induce uniform nucleation. This method has shown great promise for large-area perovskite solar cells; for instance, nitrogen-assisted drying achieved efficiencies of 11.6% on 47.3 cm² modules, while high-pressure nitrogen and vacuum flash processes reached 19.4% on 40×40 cm² modules. Recent innovations, including hot gas flow and near-infrared radiation, have further improved film densification and reproducibility, with record efficiencies of 23.28% on 22.96 cm² areas using low-toxic solvents like N-ethyl-2-pyrrolidone. Slot-die coating is currently the dominant technique for large-area perovskite solar cell production, with established production lines capable of square-meter-scale fabrication.

Spray-Coating

Spray-coating deposits perovskite precursor solutions through pressurized spraying, making it suitable for large-area applications. However, it often struggles with achieving uniform, high-quality films, leading to limited adoption in both laboratory and industrial settings for perovskite solar cells. Efforts to improve spray-coating have focused on optimizing nozzle design and solvent systems, but it remains less prevalent compared to other methods.

Table 1 summarizes the key fabrication methods for perovskite solar cells, highlighting their principles, advantages, and limitations.

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Typical Efficiency on Large Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spin-Coating | Centrifugal force distribution | Simple, reproducible | Radial thickness variation, limited to small areas | ~8.7% on 60 cm² |

| Blade-Coating | Mechanical blade movement | Scalable, controllable thickness | Slow solvent evaporation, lower efficiency | ~16.5% on 25 cm² |

| Slot-Die Coating | Coating bead formation | Precise thickness control, high throughput | Requires辅助 drying, complex setup | ~23.3% on 23 cm² |

| Spray-Coating | Pressure-based spraying | Large-area capability | Poor uniformity, low adoption | Variable, generally low |

The efficiency of a perovskite solar cell can be modeled using the photon-to-electron conversion efficiency (PCE) formula: $$PCE = \frac{J_{sc} \times V_{oc} \times FF}{P_{in}}$$ where \(J_{sc}\) is the short-circuit current density, \(V_{oc}\) is the open-circuit voltage, \(FF\) is the fill factor, and \(P_{in}\) is the incident light power. For large-area perovskite solar cells, factors like series resistance and shunt losses become significant, often reducing FF and overall PCE.

Flexible Perovskite Solar Cells

Flexible perovskite solar cells (F-PSCs) utilize substrates such as polyethylene terephthalate (PET) or polyethylene naphthalate (PEN), offering advantages like high power-to-weight ratios and adaptability to curved surfaces, making them ideal for building-integrated photovoltaics and portable energy applications. Since their inception in 2013, F-PSCs have seen rapid efficiency improvements, reaching up to 26.61% in laboratory settings, comparable to rigid perovskite solar cells. However, mechanical stability remains a critical challenge, as bending and twisting can induce cracks, lattice distortions, and phase transitions in the perovskite layer, leading to performance degradation.

Mechanical Stability

The mechanical stability of F-PSCs is often evaluated through bending tests, where devices are subjected to repeated cycles at specific radii. Research has shown that both n-i-p and p-i-n structured F-PSCs can maintain over 90% of their initial PCE after thousands of bending cycles, demonstrating robustness. For example, devices with SnO2 electron transport layers retained 95% PCE after 6,000 bends at an 8 mm radius, while those with optimized interfaces sustained 90% after 20,000 cycles. Table 2 provides representative data on the mechanical stability of flexible perovskite solar cells, highlighting their endurance under various conditions.

| Device Structure | Initial PCE (%) | Bending Cycles | Bending Radius (mm) | PCE Retention (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PEN/ITO/SnO2/Perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Ag | 19.51 | 6,000 | 8 | 95 |

| PEN/ITO/PTAA/Perovskite/CH1007/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 21.73 | 1,000 | 5 | 95 |

| PEN/ITO/HADI-SnO2/FA0.9Cs0.1PbI3/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 22.44 | 1,000 | 5 | 90 |

| PET/ITO/SnO2/Perovskite/Spiro-OMeTAD/Au | 23.40 | 5,000 | 5 | 93 |

| PET/ITO/PEDOT:EVA/Perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag | 19.87 | 7,000 | 5 | 95 |

Performance Optimization

To enhance the mechanical stability of flexible perovskite solar cells, several strategies have been employed, including grain boundary modification, interface engineering, and the development of novel substrates. Grain boundaries in perovskite films are prone to stress concentration during bending, leading to irreversible damage. Incorporating polymers like polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), or polyurethane (PU) can suture cracks and improve mechanical robustness. For instance, cross-linked fullerene derivatives and 3D cross-linkers like sodium tetraborate have been used to enhance phase and mechanical stability, with devices retaining over 91.8% PCE after 10,000 bending cycles. Self-healing polymers, such as those based on polyurethane elastomers, enable damage repair under heating, extending the lifespan of F-PSCs.

Interface engineering focuses on strengthening adhesion between layers. Additives like ammonium formate in SnO2 electron transport layers improve interfacial adhesion, maintaining over 90% PCE after 4,000 bends. Inserting nickel oxide nanocrystal layers between the hole transport layer and perovskite enhances wettability and nucleation, achieving 19.71% PCE on 58.14 cm² modules with 95% retention after 1,000 cycles.

Novel substrates, such as copper foil or stainless steel, have been explored to expand application scenarios. Copper foil-based F-PSCs achieved 20.3% PCE with oxidation resistance, while ultra-thin stainless steel substrates (5 μm thick) enabled F-PSCs with 20.24% PCE and power-to-weight ratios exceeding 3,000 W·kg−1, demonstrating the potential for lightweight, high-performance perovskite solar cells.

Fabrication Techniques

Large-area fabrication of F-PSCs employs blade-coating and slot-die coating, but flexible substrates’ higher roughness and lower thermal stability pose challenges. Sequential deposition and roll-to-roll printing have been adopted to improve film uniformity; for example, roll-to-roll processes with nitrogen blowing in air achieved scalable production. However, substrate deformation during deposition remains an issue, leading to stress concentration and reduced yield. Using smaller substrate sizes (e.g., 182 mm × 91 mm) can minimize deformation, with modules assembled via series-parallel connections to meet application demands.

The stress-strain relationship in flexible perovskite solar cells can be described by $$ \sigma = E \epsilon $$ where \(\sigma\) is stress, \(E\) is Young’s modulus, and \(\epsilon\) is strain. Minimizing strain through substrate design and film optimization is crucial for maintaining the integrity of perovskite solar cells under mechanical loads.

Tandem Solar Cells

Tandem solar cells, which combine multiple light-absorbing layers, maximize solar spectrum utilization and achieve higher efficiencies. Perovskite-based tandem structures, particularly perovskite/perovskite and perovskite/crystalline silicon (perovskite/silicon) configurations, have gained attention. Perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells are considered highly promising for terrestrial photovoltaics, with efficiencies rapidly advancing from 13.7% in 2015 to 34.6% in 2024.

Structure of Tandem Solar Cells

Perovskite/silicon tandem solar cells typically feature a perovskite top cell stacked on a silicon bottom cell, connected through a recombination layer. This design allows the perovskite layer to absorb high-energy photons while the silicon layer captures lower-energy photons, enhancing overall efficiency. The bandgap tuning of the perovskite layer is critical; for instance, wide-bandgap perovskites (e.g., 1.6–1.8 eV) are used in tandem configurations to optimize light harvesting.

Fabrication Techniques for Perovskite/Silicon Tandem Solar Cells

To deposit high-quality perovskite films on textured silicon surfaces, which are common in silicon solar cells for anti-reflection, methods like planarization are often used. However, this can increase optical losses. Alternative approaches include two-step hybrid deposition and co-evaporation.

Two-step hybrid deposition combines solution and vapor phases: first, lead halide is evaporated onto the textured silicon, followed by infiltration with organic amine salt solutions via spin-coating, blade-coating, or slot-die coating. This method enabled conformal perovskite deposition with 25.2% efficiency, but solution-based steps limit scalability for large-area perovskite solar cells.

Co-evaporation simultaneously deposits metal halides and organic amine salts, allowing precise thickness control and uniform films on textured silicon. For example, co-evaporated formamidinium lead iodide-based perovskites achieved 24.6% efficiency with 1,000 hours of stability. However, co-evaporation suffers from low material utilization, incomplete reactions, and potential contamination, affecting reproducibility for perovskite solar cell production.

The efficiency of a tandem perovskite solar cell can be expressed as $$ \eta_{\text{tandem}} = \eta_{\text{perovskite}} + \eta_{\text{silicon}} – \eta_{\text{loss}} $$ where \(\eta_{\text{perovskite}}\) and \(\eta_{\text{silicon}}\) are the efficiencies of the individual subcells, and \(\eta_{\text{loss}}\) accounts for optical and electrical losses. Optimizing the current matching between subcells is essential, given by $$ J_{\text{perovskite}} = J_{\text{silicon}} $$ where \(J\) is the current density.

Stability Enhancement Strategies for Perovskite Solar Cells

The long-term stability of perovskite solar cells is a major bottleneck for industrialization, influenced by intrinsic factors like ion migration, organic component volatilization, and high defect densities, as well as extrinsic factors such as moisture, oxygen, temperature, and light exposure. Various strategies have been developed to address these issues.

Material Optimization

Material optimization strategies focus on enhancing the intrinsic stability of perovskite solar cells. For example, developing methylamine-free perovskite compositions improves thermal stability, while reducing PbI2 residues enhances photostability. Introducing multidimensional perovskite structures, such as 2D/3D hybrids, boosts humidity resistance. Additives like crown ethers regulate phase growth and prevent water ingress, achieving 13.8% PCE on 100 cm² modules with improved wet stability. Atomic layer deposition (ALD) of SnO2 layers inhibits interfacial reactions, enhancing light and thermal stability, with devices retaining over 95% PCE after 2,000 hours under illumination at 65°C. Additionally, SnOx/Ag electrodes without fullerene layers have demonstrated high stability, maintaining performance over extended periods.

Encapsulation Techniques

Encapsulation is crucial for protecting perovskite solar cells from environmental degradation. Traditional methods use polyolefin elastomer (POE) films and butyl rubber as encapsulation materials, combined with low-iron glass cover plates to enhance stability. Novel approaches, such as in-situ encapsulation with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), create hydrophobic barriers that prevent moisture and oxygen ingress while improving PCE by up to 8%. Advanced encapsulation not only extends the lifespan but also maintains the efficiency of perovskite solar cells under real-world conditions.

The degradation rate of perovskite solar cells can be modeled using the Arrhenius equation: $$ k = A e^{-E_a / RT} $$ where \(k\) is the rate constant, \(A\) is the pre-exponential factor, \(E_a\) is the activation energy, \(R\) is the gas constant, and \(T\) is temperature. Reducing \(k\) through material and encapsulation improvements is key to achieving commercial viability.

Conclusion and Outlook

In conclusion, organic-inorganic hybrid perovskite solar cells have demonstrated remarkable progress, with laboratory-scale efficiencies reaching 27.0%, highlighting their commercial potential. However, industrialization requires overcoming challenges in large-area fabrication, stability, and cost competitiveness. Key future directions include enhancing stability through molecular design and interface optimization, establishing standardized testing protocols for accurate outdoor performance assessment, scaling up production capabilities to gigawatt levels, and reducing costs to outperform declining silicon solar cell prices. The synergy between academic research and industrial innovation will be vital for realizing the full potential of perovskite solar cells. With concerted efforts, the complete industrialization of perovskite solar cell technology is within reach, positioning it as a cornerstone of the global energy transition.

Overall, the advancement of perovskite solar cells hinges on continuous innovation in materials, processes, and device architectures. As we move forward, addressing the trifecta of efficiency, stability, and scalability will unlock new opportunities for perovskite solar cells in diverse applications, from flexible electronics to large-scale power generation. The journey of perovskite solar cells from lab to market exemplifies the transformative power of photovoltaic research, and we are optimistic about their role in a sustainable energy future.