In recent years, I have observed a significant surge in interest surrounding perovskite solar cells due to their exceptional photoelectric conversion efficiency, low cost, minimal material usage, and compatibility with flexible processing. Among these, flexible perovskite solar cells stand out as a particularly promising direction, combining the inherent advantages of perovskite materials with the ability to conform to various shapes and surfaces. This adaptability opens up new application avenues, such as wearable electronics, building-integrated photovoltaics, and portable power sources for satellites and airships. The core appeal of flexible perovskite solar cells lies in their potential to deliver high performance while being lightweight and bendable, which is crucial for modern energy solutions. However, despite rapid progress, several challenges persist, including limited mechanical durability under bending, efficiency losses in large-area devices, and the need for low-temperature fabrication processes to accommodate flexible substrates. In this article, I will delve into the research progress of flexible perovskite solar cells, focusing on key material systems, technological advancements, and future directions. I will incorporate tables and equations to summarize critical data and relationships, providing a comprehensive overview of this dynamic field.

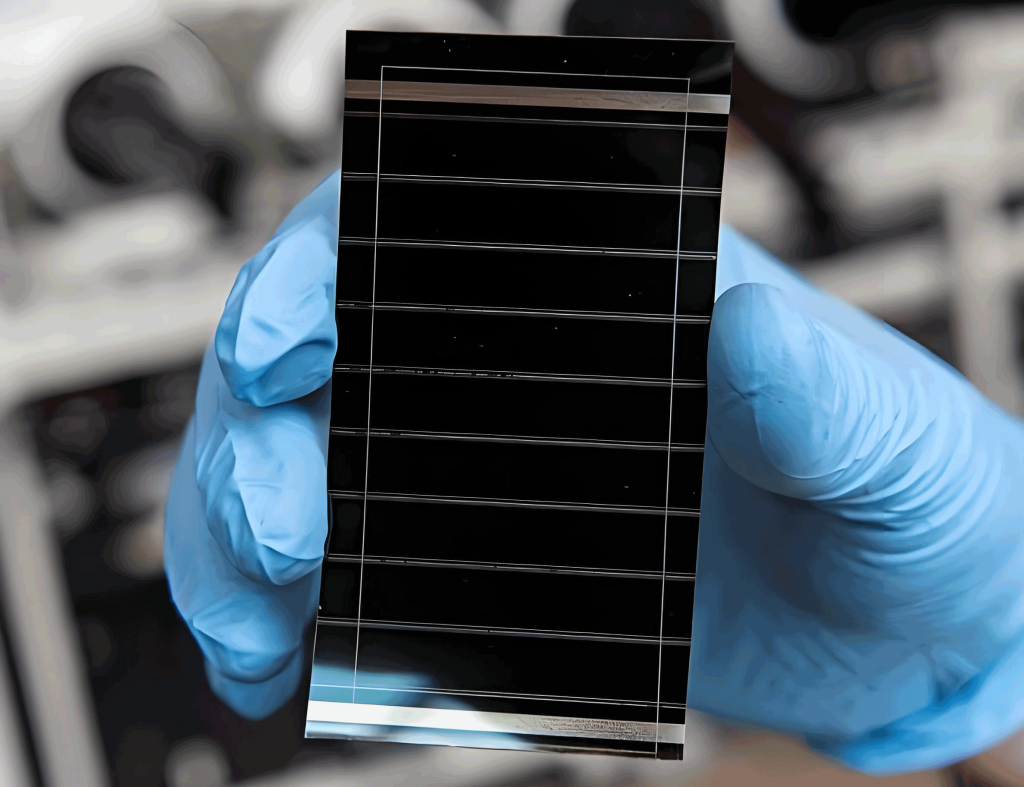

The development of flexible perovskite solar cells has been remarkable over the past decade. Since the first reported flexible perovskite solar cell in 2013 with an efficiency of just 2.26%, the field has seen exponential growth, with certified efficiencies now exceeding 23% for small-area devices. This rapid improvement underscores the potential of flexible perovskite solar cells to compete with established photovoltaic technologies. For instance, the theoretical efficiency limit for perovskite solar cells is around 31%, which is comparable to single-crystalline silicon cells, but with the added benefit of flexibility. The evolution of flexible perovskite solar cells can be attributed to innovations in material composition, interface engineering, and fabrication techniques. A key milestone was the introduction of low-temperature processed charge transport layers, which enabled the use of polymer substrates like PET and PEN without thermal degradation. Additionally, the integration of additives into the perovskite layer has enhanced crystallinity and mechanical robustness, allowing devices to withstand thousands of bending cycles. Despite these advances, the journey toward commercialization faces hurdles such as scalability, environmental stability, and the mismatch in mechanical properties between different layers in the device stack. In the following sections, I will explore these aspects in detail, highlighting how material optimizations and novel strategies are pushing the boundaries of what flexible perovskite solar cells can achieve.

One of the most critical components in flexible perovskite solar cells is the perovskite absorber layer itself. The perovskite material, typically an organic-inorganic hybrid like MAPbI₃ or mixed-cation formulations, serves as the light-harvesting medium. Its properties directly influence the device’s efficiency and mechanical flexibility. I have found that optimizing the perovskite layer involves careful control over crystallization, defect passivation, and compositional engineering. For example, introducing additives such as dimethyl sulfide (DS) or polyurethane (PU) into the precursor solution can slow down crystallization kinetics, leading to larger grain sizes and reduced defect densities. This not only improves photovoltaic performance but also enhances the mechanical integrity of the film. The general equation for the power conversion efficiency (PCE) of a perovskite solar cell is given by:

$$ \eta = \frac{J_{\text{sc}} \times V_{\text{oc}} \times \text{FF}}{P_{\text{in}}} $$

where \( J_{\text{sc}} \) is the short-circuit current density, \( V_{\text{oc}} \) is the open-circuit voltage, FF is the fill factor, and \( P_{\text{in}} \) is the incident light power density. In flexible perovskite solar cells, achieving high values for these parameters requires minimizing non-radiative recombination and ensuring efficient charge extraction, which can be addressed through interface modifications. For instance, two-dimensional (2D) perovskite layers integrated with three-dimensional (3D) perovskites have shown promise in passivating defects and improving stability. Moreover, the use of mixed cations (e.g., Cs, FA, MA) and halides (e.g., I, Br) allows for bandgap tuning, which can optimize light absorption and charge carrier dynamics. The table below summarizes the impact of various additives on the perovskite absorber layer in flexible perovskite solar cells:

| Additive | Function | Effect on Efficiency | Mechanical Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethyl Sulfide (DS) | Chelates Pb²⁺, slows crystallization | Increase to ~18.4% | Stable after 5,000 bends at 4 mm radius |

| Polyurethane (PU) | Forms elastic network, relieves stress | ~18.7% | Enhanced flexibility and durability |

| Ammonium Chloride (NH₄Cl) | Reduces trap density, improves crystallinity | ~19.7% | Better performance in large-area modules |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate (PEGDMA) | Cross-links, passivates grain boundaries | ~21.4% | Retains >86% efficiency after 5,000 bends |

In addition to additives, interface engineering plays a pivotal role in enhancing the performance of flexible perovskite solar cells. By inserting functional layers between the perovskite and charge transport layers, I have seen reductions in interfacial recombination and improvements in charge extraction. For example, sulfonated graphene oxide (s-GO) can passivate iodine vacancies at grain boundaries, leading to efficiencies over 20% and excellent bending stability. The defect density in the perovskite layer can be modeled using the following equation, which relates to non-radiative recombination:

$$ N_t = \frac{1}{\tau_{\text{eff}}} – \frac{1}{\tau_0} $$

where \( N_t \) is the trap density, \( \tau_{\text{eff}} \) is the effective carrier lifetime, and \( \tau_0 \) is the intrinsic lifetime. Lowering \( N_t \) through passivation strategies is essential for achieving high \( V_{\text{oc}} \) and FF in flexible perovskite solar cells. Furthermore, the mechanical properties of the perovskite film, such as Young’s modulus and fracture strain, determine its ability to withstand repeated bending. Studies have shown that incorporating elastic polymers or creating nanostructured scaffolds can distribute stress more evenly, preventing crack propagation and delamination. As research progresses, I believe that further optimization of the perovskite absorber layer will continue to drive efficiencies closer to the theoretical limits while maintaining flexibility.

Charge transport layers are another vital aspect of flexible perovskite solar cells, as they facilitate the separation and collection of photogenerated charge carriers. In my analysis, both electron transport layers (ETLs) and hole transport layers (HTLs) must exhibit high conductivity, appropriate energy level alignment, and mechanical compliance to avoid performance degradation under bending. For flexible perovskite solar cells, low-temperature processing is crucial because standard high-temperature treatments are incompatible with polymer substrates. Inorganic ETLs like SnO₂ and ZnO have gained popularity due to their stability and ease of low-temperature deposition using methods such as atomic layer deposition (ALD) or solution processing. However, they often suffer from brittleness, which can limit flexibility. To address this, researchers have developed doped variants, such as Li-doped SnO₂ or Al-doped ZnO, which enhance electrical properties and reduce hysteresis. The energy level alignment between the perovskite and charge transport layers can be described by the following relation for efficient charge transfer:

$$ \Delta E = E_{\text{CB, ETL}} – E_{\text{CB, Perovskite}} $$

where \( \Delta E \) should be minimal for electrons and similarly for holes in HTLs. Organic charge transport materials, such as PCBM for ETLs and Spiro-OMeTAD or PEDOT:PSS for HTLs, offer better mechanical flexibility but may require additives to improve stability and conductivity. For instance, modifying PEDOT:PSS with polymer electrolytes like PSS-Na can optimize its work function and enhance hole extraction in inverted flexible perovskite solar cells. The table below compares different charge transport materials used in flexible perovskite solar cells:

| Material Type | Examples | Processing Temperature | Advantages | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inorganic ETL | SnO₂, ZnO | ≤150°C | High stability, good charge mobility | Brittle, requires doping for flexibility |

| Organic ETL | PCBM | Room temperature | Excellent flexibility, solution-processable | Lower conductivity, environmental sensitivity |

| Inorganic HTL | NiOₓ, CuI | ≤150°C | High hole mobility, chemical stability | Interface defects, mechanical rigidity |

| Organic HTL | Spiro-OMeTAD, PTAA | Room temperature | Good film formation, tunable properties | Hygroscopic, requires additives |

In the context of flexible perovskite solar cells, the mechanical durability of charge transport layers is as important as their electronic properties. I have noted that layered or composite approaches, such as bilayers of PEDOT:PSS/PTAA, can create cascading energy alignments that improve charge extraction while distributing mechanical stress. Moreover, the integration of flexible interlayers, like ethylene-vinyl acetate (EVA), between the perovskite and charge transport layers can act as a glue, reducing ion migration and enhancing bending stability. The sheet resistance of these layers, especially in large-area devices, must be minimized to avoid efficiency losses, which can be expressed as:

$$ R_s = \rho \frac{L}{A} $$

where \( R_s \) is the sheet resistance, \( \rho \) is the resistivity, \( L \) is the length, and \( A \) is the cross-sectional area. For flexible perovskite solar cells, achieving low \( R_s \) with transparent electrodes is critical, and I will discuss this further in the section on electrodes. Overall, the ongoing development of charge transport layers focuses on balancing electronic performance with mechanical resilience, which is essential for the real-world application of flexible perovskite solar cells.

The substrate and transparent conductive electrodes form the backbone of flexible perovskite solar cells, providing structural support and enabling light ingress and current collection. In my experience, the choice of substrate directly impacts the device’s flexibility, stability, and processing conditions. Common polymer substrates like polyethylene terephthalate (PET) and polyethylene naphthalate (PEN) offer good transparency and mechanical endurance but have limited thermal stability, typically resisting temperatures up to 150°C. This constraint necessitates low-temperature fabrication processes for all functional layers in flexible perovskite solar cells. More advanced substrates, such as colorless polyimide (CPI) or ultra-thin glass, provide better thermal and barrier properties but at a higher cost. The water vapor transmission rate (WVTR) of the substrate is a key factor in determining the environmental stability of flexible perovskite solar cells, as moisture ingress can degrade the perovskite layer. The WVTR can be quantified as:

$$ \text{WVTR} = \frac{\Delta m}{A \cdot \Delta t} $$

where \( \Delta m \) is the mass change, \( A \) is the area, and \( \Delta t \) is the time. For long-term operation, substrates with low WVTR are preferred, and additional encapsulation layers are often applied to flexible perovskite solar cells to enhance durability.

Transparent conductive electrodes (TCEs) are equally critical, as they must combine high optical transparency with low sheet resistance and excellent flexibility. Indium tin oxide (ITO) is widely used but tends to crack under repeated bending due to its inherent brittleness. To overcome this, I have explored alternative TCEs such as silver nanowires (Ag-NWs), conductive polymers like PEDOT:PSS, and carbon-based materials including graphene and carbon nanotubes (CNTs). These materials offer superior mechanical properties, with some devices maintaining performance after thousands of bending cycles at small radii. For example, graphene electrodes have enabled flexible perovskite solar cells with efficiencies over 16% and minimal degradation under bending. The optical transmittance \( T \) and sheet resistance \( R_s \) of TCEs are often trade-offs, but this can be optimized using the figure of merit (FoM):

$$ \text{FoM} = \frac{T^{10}}{R_s} $$

where higher FoM values indicate better overall performance. In large-area flexible perovskite solar cells, the electrode’s conductivity becomes even more important to minimize resistive losses. The table below summarizes various electrode options for flexible perovskite solar cells:

| Electrode Material | Transparency (%) | Sheet Resistance (Ω/sq) | Flexibility | Application in F-PSCs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITO | ~85 | 10-20 | Poor (cracks easily) | Common but limited by brittleness |

| Ag Nanowires | ~90 | 10-50 | Excellent | High efficiency, stable under bending |

| Graphene | ~90 | 30-100 | Very good | Used in efficient, bendable devices |

| PEDOT:PSS composites | ~80 | 50-200 | Good | Solution-processable, flexible |

In addition to material choices, the architecture of flexible perovskite solar cells plays a significant role in their performance. Inverted (p-i-n) structures, where the hole transport layer is deposited before the perovskite, often show better compatibility with flexible substrates due to milder processing conditions. For instance, I have seen that devices using NiOₓ as the HTL and SnO₂ as the ETL in an inverted configuration achieve efficiencies above 20% with robust bending stability. The integration of these components must account for thermal expansion coefficients to prevent delamination under stress. As research advances, the development of stretchable and fully printable electrodes could further expand the applications of flexible perovskite solar cells, making them integral to next-generation energy systems.

Looking ahead, the future of flexible perovskite solar cells hinges on addressing scalability and stability challenges. Large-area module fabrication introduces issues like uniformity defects, increased series resistance, and interconnection losses, which can be modeled using the following equation for module efficiency:

$$ \eta_{\text{module}} = \eta_{\text{cell}} \times (1 – \text{FF}_{\text{loss}}) \times (1 – \text{area}_{\text{loss}}) $$

where \( \text{FF}_{\text{loss}} \) and \( \text{area}_{\text{loss}} \) account for fill factor degradation and inactive areas, respectively. I believe that advancements in slot-die coating, inkjet printing, and roll-to-roll processes will enable the mass production of efficient flexible perovskite solar cells. Moreover, encapsulation techniques using multilayer barriers can protect against moisture and oxygen, extending operational lifetimes. In conclusion, flexible perovskite solar cells represent a transformative technology with the potential to revolutionize portable and integrated photovoltaics. Through continued innovation in materials science and engineering, I am confident that these devices will overcome current limitations and achieve widespread adoption, contributing significantly to global sustainable energy goals.