The global transition towards carbon neutrality has propelled energy storage, particularly lithium-ion battery energy storage systems (LIBESS), into a pivotal role within modern power infrastructure. While enabling the integration of volatile renewable sources, the rapid, large-scale deployment of these systems has unveiled a critical bottleneck: their inherent susceptibility to fire and explosion hazards. Catastrophic failures, witnessed in numerous incidents worldwide, underscore the complex, multi-physics nature of thermal runaway and the existing gaps in holistic safety management. This persistent safety challenge threatens not only economic assets but also public confidence, thereby potentially hindering the sustainable advancement of the clean energy sector. Our review systematically adopts a “mechanism–assessment–prevention and control” framework. We dissect the causal chains and evolution dynamics of fire and explosion accidents in LIBESS, identify the multi-level risk characteristics from cell failure to system-wide propagation, and critically evaluate the current technological landscape for safety assurance. By synthesizing the state-of-the-art and highlighting persistent challenges—such as fragmented technological advances, cost-benefit imbalances, and lifecycle management deficiencies—we aim to chart a path toward enhanced safety resilience for lithium-ion battery energy storage systems, which is fundamental for the high-quality development of new energy paradigms.

1. Root Causes and Evolution Mechanisms of Failure

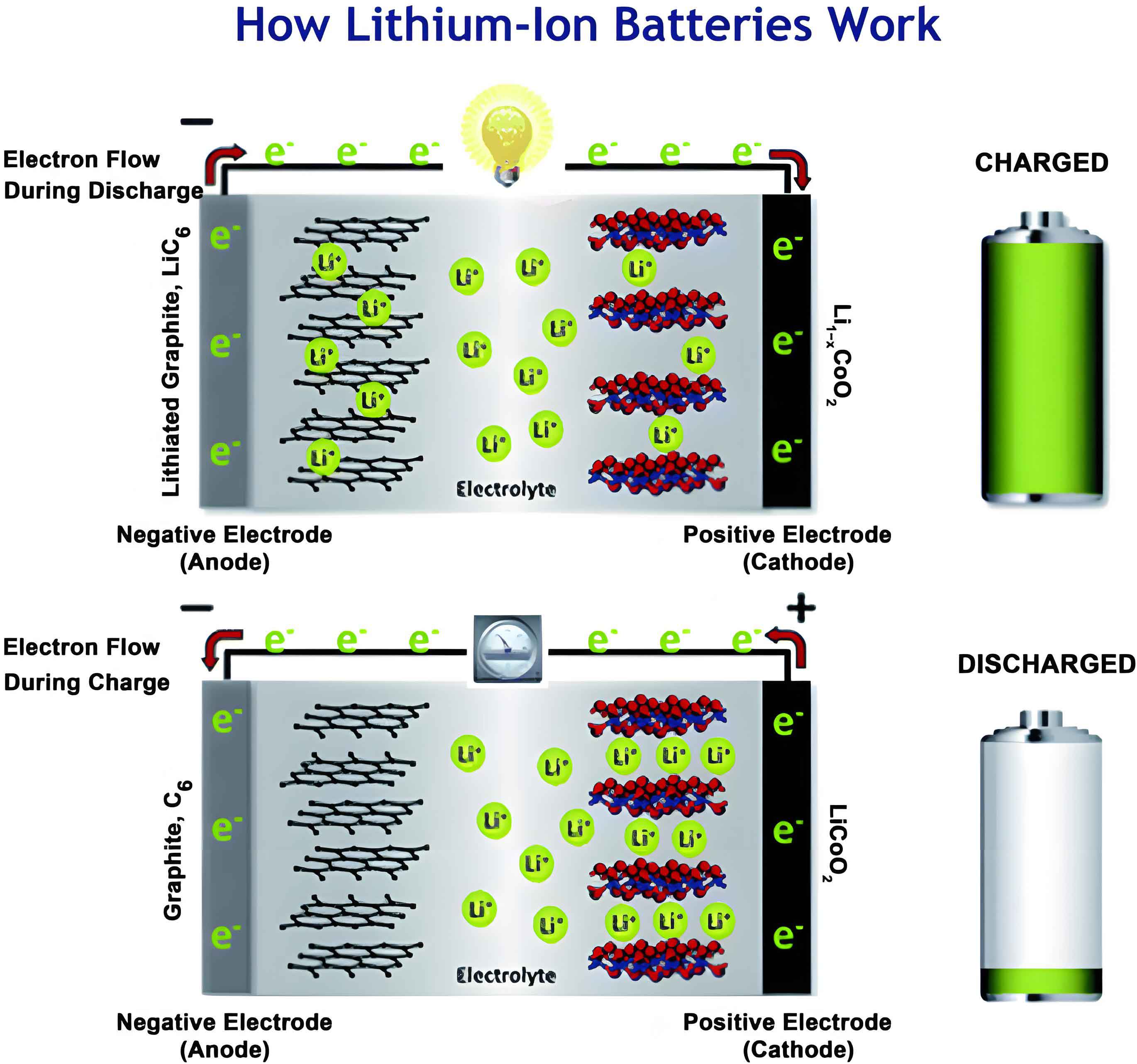

The genesis of catastrophic failure in a lithium-ion battery is universally attributed to the phenomenon of thermal runaway (TR). This is a self-accelerating, exothermic process typically triggered by abusive conditions—thermal, electrical, or mechanical—or latent internal defects. These triggers are not isolated; they exhibit a cascading, interlinked failure relationship, with internal short circuit (ISC) often being a common terminal outcome.

- Electrical Abuse: Overcharging, deep discharging, or high-rate operation can induce lithium plating, forming dendritic structures that pierce the separator, or corrode current collectors, leading to an ISC.

- Mechanical Abuse: Collision, compression, or penetration directly compromises the structural integrity of the battery cell, causing electrode contact and short-circuiting.

- Thermal Abuse: Localized overheating or exposure to high ambient temperatures can cause separator meltdown and shrinkage or accelerate electrolyte decomposition, facilitating an ISC.

Once an ISC is established, the localized Joule heating ($P_{Joule} = I_{short}^2 \cdot R_{internal}$) combined with heat released from chemical reactions initiates a vicious cycle. The temperature rise catalyzes a sequence of parasitic exothermic reactions: decomposition of the solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) layer, reaction between the lithiated anode and electrolyte, separator collapse, cathode material decomposition, and electrolyte decomposition. The cumulative heat generation rate ($\dot{Q}_{gen}$) overwhelms the heat dissipation rate ($\dot{Q}_{diss}$), leading to uncontrollable temperature escalation. This process can be conceptually described by the energy balance equation for a battery cell:

$$\rho C_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \dot{Q}_{gen}(T, SOC, \dots)$$

where $\rho$, $C_p$, and $k$ are density, heat capacity, and thermal conductivity, respectively, and $\dot{Q}_{gen}$ is a strong, nonlinear function of temperature and state of charge (SOC).

As internal pressure builds from gas generation, the cell vent opens, ejecting a mixture of combustible gases (e.g., $H_2$, $CO$, $C_2H_4$), electrolyte vapor, and hot particulate matter. If this jet encounters an ignition source—such as the ejected hot particles, arcing from damaged electrical components, or the cell’s own hot surface—a jet fire ensues. If unignited, the gases may accumulate within the confined space of a battery module or container. When their concentration reaches the Lower Explosive Limit (LEL) and an ignition source is present, a violent deflagration or even detonation can occur, posing severe threats to personnel and infrastructure.

2. Multi-Scale Fire and Explosion Hazard Analysis

2.1 Single-Cell Level Hazard Characterization

The hazard profile of a single lithium-ion battery is intrinsically linked to its chemistry. Cathode material is a primary determinant of thermal stability. Generally, the hierarchy is: LiFePO$_4$ (LFP) > LiMn$_2$O$_4$ (LMO) > LiNi$_x$Co$_y$Mn$_z$O$_2$ (NCM) > LiNi$_x$Co$_y$Al$_z$O$_2$ (NCA) > LiCoO$_2$ (LCO). High-nickel NCM cathodes, favored for high energy density, exhibit poorer thermal stability, releasing active oxygen at lower temperatures which fuels intense reactions. In contrast, LFP batteries, dominant in stationary storage due to their lower TR probability, possess superior structural and thermal stability. However, this creates a critical trade-off: while LFP cells are harder to trigger into TR, their vent gas typically contains higher concentrations of highly flammable gases like $H_2$ and $C_2H_4$ due to the lack of internal oxygen from the cathode to oxidize them. This results in vent gases with a lower LEL, higher laminar burning velocity, and potentially higher explosion overpressure compared to NCM cells, indicating a significant external explosion hazard.

The role of electrolyte vapor is paramount. Common carbonate solvents (DMC, EMC, DEC) have low boiling points and readily vaporize during TR. Their explosion parameters are comparable to common hydrocarbons. In a realistic multi-phase ejecta (gas + vapor + aerosols), the presence of electrolyte vapor can broaden the explosive concentration range and increase the explosion severity, creating a more dangerous scenario than gaseous components alone. The combustion process of a lithium-ion battery is also unique, often characterized by multiple jet-fire stages separated by stable burning phases, with the total heat release rate heavily dependent on the initial SOC.

| Cathode Material | Relative Thermal Stability | Typical TR Gas Composition (Key Species) | Primary Hazard Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| LiFePO4 (LFP) | High | High H2, C2H4; Lower CO/CO2 | High explosivity of vent gas, lower LEL. |

| LiNixCoyMnzO2 (NCM) | Medium-Low | High CO, CO2; Lower H2 | Intense internal heat release, higher TR propensity. |

| LiNixCoyAlzO2 (NCA) | Low | Similar to NCM | Similar to NCM, with potential for oxygen release. |

2.2 Module, Pack, and Container Level Hazard Propagation

The primary risk in a lithium-ion battery energy storage system lies not in a single cell failure, but in the propagation of thermal runaway (TRP) to neighboring cells, leading to a cascading failure that can engulf an entire system. The characteristics of TRP are influenced by a multitude of factors:

- Cell Format & Connection: Cylindrical cells may propagate less via conduction than prismatic or pouch cells due to smaller contact areas. Parallel electrical connections can accelerate TRP by dumping current into a failing cell.

- Thermal Management System (TMS): Effective cooling is the first line of defense. Air cooling, liquid cooling (especially cold plate designs), and phase change materials (PCMs) are employed to maintain temperature homogeneity and remove heat. Liquid cooling, particularly direct immersion cooling, is gaining traction for its superior heat transfer and inherent fire suppression potential.

- System Design & Geometry: The spacing between cells, module enclosure design, venting paths, and container ventilation critically affect gas accumulation, heat transfer via radiation and convection, and ultimately, the speed and mode of propagation.

Propagation often exhibits complex spatiotemporal patterns: sequential horizontal spread within a module (driven by conduction) and rapid, sometimes seemingly simultaneous, vertical spread between modules (driven by flame impingement and hot gas accumulation). When propagation becomes uncontrolled at the pack level, the hazard escalates to the container scale. Here, the deflagration of accumulated gases can generate significant overpressure, threatening structural integrity. The explosion hazard is dynamic, depending on ventilation rates, ignition timing (immediate vs. delayed), and the evolving gas composition. Quantifying these system-level hazards remains a significant challenge, as it requires coupling multi-phase ejection models with computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for gas dispersion and combustion, all while accounting for the inherent stochasticity of the failure process.

3. Current Landscape of Prevention and Mitigation Technologies

3.1 Intrinsic Battery Safety

Enhancing the inherent safety of the lithium-ion battery itself is the most fundamental approach. This spans material innovation, cell design, and manufacturing precision.

- Material Advancements: Research focuses on stabilizing cathode materials via doping or surface coatings, developing non-flammable electrolytes or adding flame-retardant additives, employing more thermally stable ceramic-coated or non-woven separators, and improving anode stability. The ultimate goal is solid-state batteries, which replace the liquid electrolyte with a solid conductor, theoretically eliminating leakage and flammability, though new failure modes are under investigation.

- Functional Components: Innovative internal designs include integrating thermally responsive materials that can “switch off” current flow upon overheating or release quenching agents to suppress internal reactions. Examples include thermoresponsive polymer switches (TRPS) and internal flame-retardant layers.

- Manufacturing Quality: Rigorous control over electrode coating uniformity, impurity levels, tab welding, and assembly cleanliness is essential to minimize latent defects that could lead to spontaneous internal short circuits.

3.2 Monitoring and Early Warning

Early detection of precursor signals is crucial for preventing escalation. Modern Battery Management Systems (BMS) and supplementary sensors monitor various parameters. The effectiveness and challenges of different signals are summarized below:

| Monitoring Signal | Advantages | Challenges & Limitations | Typical Early Warning Lead Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage | Standard BMS parameter; models can detect anomalies. | Thresholds are condition-dependent; signals may appear late in the TR chain. | Minutes to seconds before venting (varies with fault). |

| Temperature (Surface) | Standard BMS parameter; simple to implement. | Significant lag compared to core temperature; external heating can mask internal faults. | Tens of seconds to minutes before venting. |

| Temperature (Internal) | Provides true core temperature; earliest thermal warning. | Requires embedded sensors (e.g., fiber optics, thin-film); increases cost/complexity. | Minutes before venting. |

| Gas (e.g., H2, CO) | H2 can indicate early lithium plating; CO/VOC signal clear during SEI breakdown. | Sensor placement critical for response time; cross-sensitivity; may indicate irreversible TR onset. | H2: potentially very early (plating). CO/VOC: minutes before venting. |

| Expansion Force/Pressure | Very sensitive to internal gas generation; reported as one of the earliest mechanical signals. | Influenced by SOC, aging, and mechanical constraints; requires robust force/pressure sensors. | Can be several minutes earlier than voltage/temperature signals. |

| Acoustic (Venting Sound) | Clear, direct indicator of venting event. | Very late signal; requires robust noise discrimination. | Seconds before ignition; no lead time to prevent TR. |

The future lies in multi-signal fusion and data-driven predictive analytics. Combining signals like expansion force, internal temperature, and gas composition within an AI/ML framework can improve detection reliability, reduce false alarms, and provide a prognostic estimate of the time-to-failure, enabling proactive intervention.

3.3 Fire Suppression, Explosion Protection, and Thermal Management

These are the last lines of defense, activated when prevention and early warning fail.

- Fire Suppression: Lithium-ion battery fires are challenging due to deep-seated chemical reactions and reignition risk. Common agents include:

- Clean Agent Gases (e.g., C6F12O, HFC-227ea): Effective at extinguishing open flames quickly but often lack cooling capacity, leading to high reignition probability.

- Water Mist / Sprinklers: Excellent cooling, prevents reignition, and is cost-effective. However, water can cause electrical short circuits in non-faulty equipment. A hybrid approach (gas for rapid flame knock-down followed by water for cooling) is common.

- Direct Immersion Cooling: Using dielectric fluid as both coolant and immersion medium physically isolates cells from oxygen and provides continuous cooling, effectively suppressing TRP.

System design is evolving from single-point discharge to distributed, targeted application (e.g., at the module or pack level) and integration with early warning for automated, staged response.

- Explosion Protection: For containerized systems, preventing gas accumulation is key. This involves:

- Passive Venting: Designing adequate venting areas based on standards like NFPA 68 to safely release overpressure and avoid structural rupture.

- Active Ventilation: Using explosion-proof fans to maintain gas concentrations below the LEL. Conflict arises if fire suppression requires a sealed atmosphere.

- Inerting: Flooding the enclosure with inert gas (e.g., $N_2$) to lower the oxygen concentration below the Minimum Oxygen Concentration (MOC) for combustion.

- Advanced Thermal Management: Beyond basic cooling, new materials are being integrated. Aerogels or thermally regulative materials that switch from conductive to insulating states at high temperatures can be used to block heat transfer during a TR event, compartmentalizing the failure.

| Thermal Management Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air Cooling | Forced convection of air over cells. | Simple, low cost, easy maintenance. | Low heat capacity & conductivity; inefficient for high-density, high-power systems. |

| Liquid Cooling (Cold Plate) | Coolant flows through channels in contact with module/cell surfaces. | High cooling efficiency, good temperature uniformity. | More complex system, risk of leakage, potential single point of failure. |

| Phase Change Material (PCM) | Material absorbs heat as it changes phase (solid-liquid), buffering temperature rise. | Passive, no energy consumption, good for peak loads. | Low thermal conductivity, finite latent heat, may not handle sustained TR heat. |

| Direct Immersion Cooling | Cells are fully submerged in dielectric fluid. | Exceptional cooling & thermal uniformity; inherent fire suppression; isolates cells. | High fluid cost, increased weight, system complexity, long-term fluid-cell compatibility. |

4. Evolving Trends and Persistent Challenges

4.1 Promising Trends

- Intrinsic Safety via Solid-State Batteries: The pursuit of all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries represents a paradigm shift, aiming to eliminate flammable electrolytes. While commercialization faces hurdles (interface resistance, cost), it holds the greatest promise for ultimate safety.

- Digitalization and Intelligence: The integration of AI/ML for state estimation, fault prediction, and digital twin technology is revolutionizing safety management. Smart BMS, cloud-based analytics platforms, and predictive maintenance are moving the industry from reactive to proactive safety paradigms.

- Standardization and Regulatory Maturation: International standards (UL 9540, NFPA 855, IEC 62933) are rapidly evolving to keep pace with technology. New testing requirements, like large-scale fire tests (UL 9540A), are driving better system-level design. Global harmonization of standards is crucial for safe market growth.

4.2 Core Challenges

- Systemic Risk vs. Component Optimization: Significant research advances occur at the material or single-cell level, but systemic risks arising from interactions between thousands of cells, the TMS, BMS, and enclosure in real-world conditions are less understood. An optimized cell in a poorly designed system remains unsafe.

- The Cost-Safety Trade-off: Adding safety features (sensors, high-end materials, sophisticated cooling/fire suppression) increases capital expenditure. In a highly cost-competitive market, there is constant pressure to minimize these “non-energy” components, potentially compromising safety margins.

- Emerging Scenarios and Lifecycle Risks:

- Gigawatt-hour-scale Systems: Traditional protection strategies may not scale effectively. The system-level failure probability increases non-linearly with size.

- Second-Life Batteries: Repurposing used electric vehicle batteries for stationary storage introduces unknowns regarding heterogeneous aging and the definition of safety thresholds for retired cells, creating new risk profiles.

- Extreme Environment Operation: Standards and designs often assume temperate climates. Operation in extreme cold, heat, or humidity poses unaddressed challenges to battery performance and safety systems.

- Fragmented Lifecycle Data: Safety-critical data from manufacturing, field operation, and eventual failure is often siloed. A lack of “birth-to-death” traceability hinders root-cause analysis, predictive model training, and the establishment of reliable lifecycle safety boundaries.

5. Strategic Recommendations for Enhanced Safety Resilience

To navigate these challenges and foster the safe, sustainable growth of the lithium-ion battery energy storage industry, a multi-faceted, collaborative approach is essential.

- Deepen Fundamental and Applied Research: Prioritize funding for multi-physics modeling of TR and TRP across scales (cell to system), advanced in-operando diagnostic techniques, and the development of “fail-safe” electrochemical couples and materials. Research must bridge the gap between laboratory discovery and engineered system implementation.

- Champion Systemic, Integrated Safety-by-Design: Safety must be a primary design criterion from the outset, not an add-on. This requires close collaboration between cell manufacturers, system integrators, and component suppliers to optimize the interplay between battery chemistry, thermal management, structural design, and control software. Modular and standardized designs can enhance both safety and economic viability.

- Implement Robust, Data-Driven Lifecycle Management: Establish digital passports for critical lithium-ion battery components to track key parameters throughout their life. Develop and validate AI-powered algorithms for accurate State of Health (SOH) and Remaining Useful Life (RUL) estimation, enabling predictive maintenance and informed decision-making for second-life applications.

- Strengthen and Harmonize the Regulatory Framework: Continue to update international and national standards based on the latest research and incident learnings. Promote global alignment of safety testing and certification protocols to ensure a high baseline of safety while facilitating international trade. Regulations should incentivize safety investments.

- Foster Industry-Wide Collaboration and Transparency: Encourage the sharing of anonymized failure data and best practices across the industry through consortia or neutral bodies. A culture of transparency regarding incidents is vital for collective learning and improvement.

- Develop Specialized Emergency Response Protocols and Insurance Models: Fire departments and first responders need specialized training and equipment for lithium-ion battery energy storage system incidents. The insurance industry should develop products that reflect the true risk profile, potentially offering lower premiums for systems with certified, advanced safety features, thus creating a market-based incentive for safety.

The pathway to ubiquitous and secure energy storage hinges on our ability to master the complex safety landscape of lithium-ion battery technology. By integrating advances in intrinsic material safety, intelligent monitoring, robust system engineering, and proactive lifecycle management within a supportive regulatory and collaborative ecosystem, we can mitigate the risks of fire and explosion. This will unlock the full potential of lithium-ion battery energy storage systems as a cornerstone of a resilient, decarbonized energy future.

| Standard / Regulation | Issuing Body | Key Focus / Recent Updates | Impact on Safety Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| UL 9540 / 9540A | Underwriters Laboratories (UL) | Safety of ESS equipment. 9540A specifies large-scale fire testing methodology. | Drives design validation through realistic fire propagation testing; affects system sizing and spacing. |

| NFPA 855 | National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) | Standard for the Installation of Stationary Energy Storage Systems. | Mandates separation distances, fire ratings, suppression systems, and hazard mitigation analysis. |

| IEC 62933 Series | International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC) | Comprehensive series covering safety, performance, environmental aspects of ESS. | Provides international benchmarks for safety requirements and test procedures. |

| GB/T 36276, GB 51048 (China) | Standardization Administration of China (SAC) | Safety requirements and design code for electrochemical energy storage power stations. | Sets national baseline for fire protection, layout, and emergency response in China’s massive ESS market. |