The proliferation of renewable energy sources and the imperative for grid stability have propelled electrochemical energy storage to the forefront of modern power systems. Among various technologies, lithium-ion batteries, prized for their high energy density, long cycle life, and decreasing cost, have become the cornerstone of contemporary battery energy storage system installations. Their deployment scales from residential units to grid-scale facilities, underscoring their critical role in the energy transition. However, the high energy density that makes them advantageous also harbors a significant safety risk: thermal runaway (TR). This exothermic, self-accelerating decomposition reaction within a cell can lead to fire, explosion, and the propagation of failure to adjacent cells, posing severe threats to life, property, and grid infrastructure. High-profile incidents have tragically highlighted these dangers, making the effective suppression of thermal runaway a paramount research and engineering challenge for safe battery energy storage system operation.

Traditional fire suppression agents, including water, aerosol, and clean gases like heptafluoropropane, have shown limited effectiveness against lithium-ion battery fires. Water, while effective at cooling, can cause electrical short circuits in unaffected modules, requires massive quantities, and may increase the generation of toxic gases like hydrogen fluoride (HF) and carbon monoxide (CO). This necessitates the exploration of alternative, more effective, and electrically non-conductive suppressants. Liquid nitrogen (LN2) presents a compelling candidate due to its exceptional physical properties. It possesses a high latent heat of vaporization (approximately 199 kJ/kg), enabling rapid heat extraction from hot surfaces. Upon vaporization, it produces inert nitrogen gas, which dilutes oxygen and suppresses combustion. Furthermore, it is electrically non-conductive, chemically inert, and leaves no residue, making it potentially ideal for protecting sensitive and high-value battery energy storage system equipment. While previous studies have demonstrated LN2‘s efficacy on small-format cylindrical cells, its performance on the large-format, prismatic lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries commonly used in stationary storage remains less explored. This work aims to systematically investigate the suppression effect of LN2 on thermal runaway in a commercial 65 Ah LFP battery, focusing on the influence of injection timing and quantity, thereby contributing to the safety design of large-scale battery energy storage system.

Thermal Runaway Mechanism and Stages

Thermal runaway in a lithium-ion battery is a complex cascade of exothermic chemical reactions initiated when the cell’s internal temperature exceeds a critical threshold. The process is self-accelerating because the heat generated by these reactions further raises the temperature, driving even faster reaction rates. This can be fundamentally described by the Arrhenius law, where the reaction rate constant \( k \) is a function of temperature \( T \):

$$ k = A e^{-E_a/(RT)} $$

where \( A \) is the pre-exponential factor, \( E_a \) is the activation energy, and \( R \) is the universal gas constant. The overall heat generation rate \( \dot{Q}_{gen} \) within a failing cell is the sum of contributions from several sequential reactions, which can outpace the heat dissipation rate \( \dot{Q}_{diss} \), leading to catastrophic temperature rise. For a typical LFP battery subjected to external heating, the TR process can be delineated into four distinct stages, as summarized in the table below.

| Stage | Key Processes & Triggers | Observable Phenomena | Temperature Range (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. External Heating | Heat input from an external source (e.g., heater, adjacent failing cell). SEI (Solid Electrolyte Interphase) layer begins to decompose at ~80-120°C, releasing minor heat and gases (CO2, CH4). | Linear temperature rise dominated by external heat. Battery may swell slightly. | Ambient to ~90°C |

| 2. Self-heating & Venting | Decomposition of SEI becomes significant. Internal pressure builds from gas generation. Safety vent opens to release pressure. | Temperature rise accelerates. Audible venting or jetting of gas and electrolyte vapor. A sharp but temporary temperature drop may occur at vent opening. | ~90°C to ~130°C |

| 3. Thermal Runaway | Exothermic reactions of electrolyte with anode, cathode decomposition (LFP is more stable but still decomposes), and electrolyte combustion (if ignited) occur violently. This is the point of no return. | Rapid, exponential temperature rise (dT/dt > 1°C/s). Intense jetting of flame, sparks, and smoke. Peak temperatures can exceed 500°C. | ~130°C to >400°C |

| 4. Burnout / Cooling | Active materials are largely consumed. Heat generation ceases. Cell cools down via heat transfer to surroundings. | Flames subside. Temperature gradually decreases. Cell casing remains very hot. | From peak down |

The critical transition from Stage 2 to Stage 3 is often defined by a specific temperature or, more robustly, by a sustained high rate of temperature increase (e.g., >0.2 °C/s). The total energy released during a TR event in a large-format cell for a battery energy storage system is substantial, governed by the cell’s mass, specific heat capacity, and the enthalpy of the chemical reactions. The total sensible heat \( Q_{total} \) a cell can release from its peak TR temperature \( T_{max} \) down to ambient \( T_{amb} \) is:

$$ Q_{total} = m_{cell} c_{p,cell} (T_{max} – T_{amb}) + \sum \Delta H_{reactions} $$

where \( m_{cell} \) is the cell mass and \( c_{p,cell} \) is its effective specific heat capacity. Suppressing TR requires an agent that can absorb this energy faster than it is generated.

Experimental Methodology for Suppression Evaluation

To evaluate the efficacy of LN2, a controlled experimental platform was established. The test specimen was a commercial prismatic LFP battery with a nominal capacity of 65 Ah, a format representative of those integrated into industrial battery energy storage system racks. All tests were conducted at 100% State of Charge (SOC), representing the worst-case hazard scenario. Thermal runaway was triggered by a controlled heating pad attached to one side of the cell.

The suppression system consisted of a pressurized LN2 dewar, a solenoid valve, and a delivery pipe terminating in a nozzle positioned directly above the cell’s vent. Temperature was monitored at multiple points on the cell surface and within the test chamber using K-type thermocouples. A key aspect of the study was to define specific intervention points based on the characterized TR stages of the cell (from blank tests without suppression):

- Point A (Pre-venting): Cell surface temperature ~90°C. Intervention occurs before the safety valve opens, during the early self-heating phase.

- Point B (TR Onset): Cell surface temperature ~135°C. Intervention occurs just as the cell enters the rapid temperature rise phase (TR onset).

- Point C (Full TR): Cell surface temperature ~320°C. Intervention occurs during the most violent period of TR, with potential flaming jetting.

The experimental matrix was designed to isolate the effects of injection timing and mass, as shown in the following table. The external heater was switched off simultaneously with the start of LN2 injection.

| Test Case | Injection Timing (Point) | LN2 Mass [kg] | Primary Investigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A (Pre-venting, 90°C) | 1.2 | Effect of Injection Timing |

| 2 | B (TR Onset, 135°C) | 1.2 | |

| 3 & 6 | B (TR Onset, 135°C) | 6.7 | |

| 4 | C (Full TR, 320°C) | 7.2 | |

| 5 | B (TR Onset, 135°C) | 6.2 | Effect of LN2 Mass |

| 6 | B (TR Onset, 135°C) | 6.7 | |

| 7 | B (TR Onset, 135°C) | 8.0 |

Results: Effect of Liquid Nitrogen Injection Timing

The timing of suppressant application proved to be critically important for the battery energy storage system safety strategy. A small dose of LN2 (1.2 kg) injected at the Pre-venting point (Case 1) was completely successful. The cell’s average temperature dropped from 78.4°C to 44.5°C. After injection stopped, the temperature only rebounded to a plateau of 58°C, well below any TR threshold, effectively preventing the event. This demonstrates the high efficiency of early intervention, likely before significant internal chain reactions have become self-sustaining.

In stark contrast, the same 1.2 kg dose applied at the TR Onset point (Case 2) failed. The cell’s temperature showed only a minor, transient decrease before resuming a rapid climb to a maximum average temperature of 233°C. While this maximum was 142°C lower than in an uncontrolled TR (375°C), it confirmed that once the cascade of exothermic reactions is firmly established, the heat generation rate can outstrip the cooling capacity of a small LN2 dose.

Success at the TR Onset stage required a significantly larger mass. Injecting 6.7 kg of LN2 at 135°C (Case 3/6) caused the cell surface temperature to plummet, reaching as low as -155°C in some locations. The average temperature dropped from 132.6°C to 4.7°C and rebounded to a stable 66.7°C post-injection, successfully arresting TR. Similarly, injecting 7.2 kg during the Full TR stage at 320°C (Case 4) was also successful. The violent flaming jet was instantly extinguished due to oxygen dilution and cooling. The average temperature fell from 313.1°C to 75.6°C, rebounding to 87.2°C, well below the danger zone. These results underscore a crucial principle for battery energy storage system protection: while early detection and intervention are most efficient, a sufficiently large cooling capacity delivered by agents like LN2 can arrest TR even in its advanced stages.

Results: Quantitative Analysis of Liquid Nitrogen Mass Effect

To quantitatively analyze the cooling effect, tests with varying LN2 masses injected at the same TR Onset timing were compared (Cases 5, 6, 7). A key metric is the net temperature suppression \( \Delta T_{m-r} \), defined as the difference between the cell’s temperature at the start of injection \( T_{max, start} \) and its peak temperature after the injection ends \( T_{re, peak} \):

$$ \Delta T_{m-r} = T_{max, start} – T_{re, peak} $$

A larger \( \Delta T_{m-r} \) indicates a stronger net cooling effect. The values calculated were 17.6°C for 6.2 kg, 65.9°C for 6.7 kg, and 103.7°C for 8.0 kg, clearly showing that increased LN2 mass enhances suppression performance.

A thermodynamic analysis provides deeper insight. Modeling the cell as a lumped thermal mass, the total theoretical heat \( Q_{LN} \) that the injected LN2 can absorb through vaporization is:

$$ Q_{LN} = m_{LN} \cdot L_{LN} $$

where \( m_{LN} \) is the mass of LN2 and \( L_{LN} \) is its latent heat of vaporization (~199 kJ/kg). However, not all of this cooling potential is applied to the battery itself; a portion is lost to cool down the surrounding fixture and air. The heat actually absorbed by the battery \( Q_{b, LN} \) can be estimated from its temperature change:

$$ Q_{b, LN} = m_{cell} c_{p,cell} (T_{max, start} – T_{re, peak}) $$

Using \( c_{p,cell} \approx 1.1 \, \text{kJ/(kg·K)} \), we can calculate two efficiency metrics:

1. Cooling Rate \( \eta_c \): The fraction of the battery’s “stored” hazardous heat that was removed by the LN2. It is the ratio of \( Q_{b, LN} \) to the total sensible heat the battery contained above its post-rebound temperature \( Q_{total} = m_{cell} c_{p,cell} (T_{max, start} – T_i) \), where \( T_i \) is the initial temperature.

2. Effective Utilization Rate \( \eta_e \): The fraction of LN2‘s total theoretical cooling capacity that was actually used to cool the battery: \( \eta_e = Q_{b, LN} / Q_{LN} \).

The calculated results are presented in the table below.

| LN2 Mass (kg) | \( Q_{LN} \) (Theoretical) [kJ] | \( Q_{b, LN} \) (Battery Absorbed) [kJ] | Cooling Rate \( \eta_c \) | Effective Utilization Rate \( \eta_e \) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6.2 | 1233.8 | 33.4 | 18.0% | 2.7% |

| 6.7 | 1333.3 | 125.4 | 57.8% | 9.4% |

| 8.0 | 1592.0 | 197.3 | 89.1% | 12.4% |

The analysis reveals critical insights for designing a battery energy storage system suppression system. While both the absolute heat removed \( Q_{b, LN} \) and the cooling rate \( \eta_c \) increase substantially with LN2 mass (the 8.0 kg dose removed ~5.9 times more heat from the battery than the 6.2 kg dose), the effective utilization rate \( \eta_e \) remains low and increases only marginally. This indicates that a significant portion of the LN2‘s cooling potential is “wasted” on cooling the enclosure and ambient air, not the battery core. This highlights an engineering challenge: optimizing nozzle design, injection direction, and enclosure geometry to maximize the transfer of cooling power to the failing cells within a dense battery energy storage system module is essential for efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Conclusion and Implications for Battery Energy Storage System Safety

This experimental investigation demonstrates that liquid nitrogen is a highly effective agent for suppressing thermal runaway in large-format LFP batteries relevant to stationary energy storage. Its dual mechanism of rapid evaporative cooling and oxygen inertization can successfully arrest the TR process. The key findings are:

- Injection Timing is Critical: Early intervention during the pre-venting or very early self-heating stage is the most efficient, requiring minimal suppressant to prevent TR. This underscores the paramount importance of a reliable, sensitive early-stage thermal detection and warning system in a battery energy storage system.

- Mass Determines Success in Advanced Stages: Once TR is established, success is contingent on delivering a sufficient cooling capacity (mass of LN2). A properly sized LN2 system can suppress even violent TR, preventing cell-to-cell propagation.

- Efficiency Requires Optimization: While more LN2 provides better cooling, its effective utilization rate on the battery itself is relatively low. System design must focus on targeted delivery to improve efficiency.

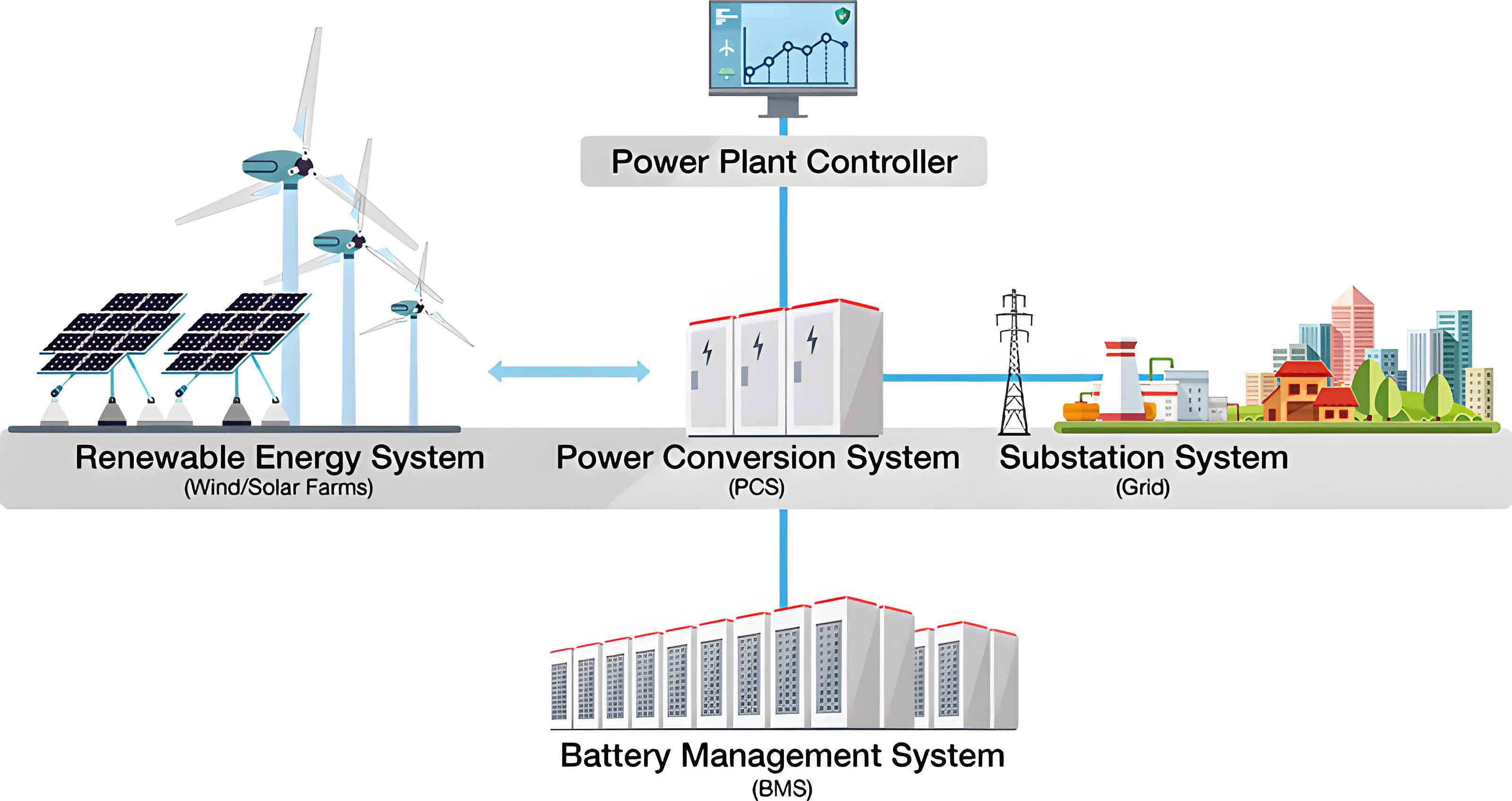

For practical implementation in a battery energy storage system, these results suggest a layered safety strategy. An ideal system would integrate:

(1) Advanced BMS with early TR detection algorithms (e.g., gas sensing, voltage/ temperature curvature analysis).

(2) Targeted, localized LN2 injection nozzles directed at individual cells or small modules within the battery energy storage system cabinet.

(3) Sizing of the LN2 reservoir based on the cooling demand for suppressing TR in a defined number of “worst-case” cells simultaneously, considering the found utilization rates.

(4) An enclosure designed to briefly contain and guide the cold nitrogen gas over the battery surfaces before venting safely.

Further research is needed to scale these findings to full module and rack levels, study the effects of partial state of charge, and investigate the long-term implications of extreme thermal cycling induced by LN2 on adjacent healthy cells. Nevertheless, this work strongly positions liquid nitrogen as a viable and powerful option for enhancing the inherent safety of lithium-ion based battery energy storage system installations.