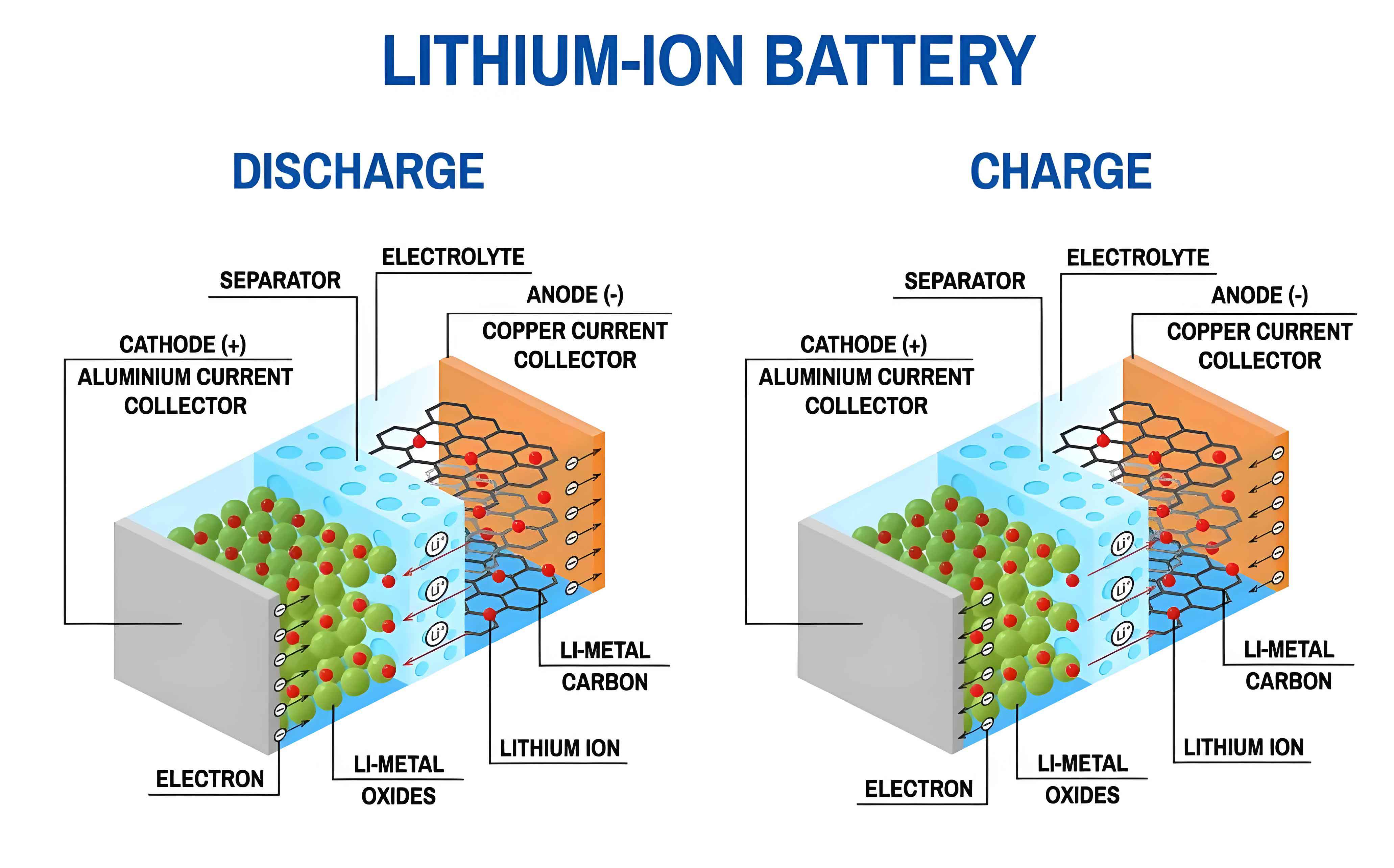

The relentless pursuit of sustainable energy solutions has positioned the lithium-ion battery as the cornerstone of modern electrochemical energy storage. Its dominance in applications ranging from portable electronics to electric vehicles and grid-scale storage is a testament to its high energy density, respectable cycle life, and continuous performance improvements. At the heart of this complex device lies the electrolyte, a critical and often vulnerable component. Functioning as the ionic conduit between the cathode and anode, the electrolyte’s composition and stability are paramount. Typically composed of lithium salts (e.g., LiPF6) dissolved in a blend of organic carbonate solvents (e.g., EC, DMC, EMC) and performance-enhancing additives, the electrolyte must maintain its integrity under a wide range of operational stresses. However, its inherent chemical reactivity and sensitivity to factors such as voltage, temperature, moisture, and material interactions make it a primary locus for degradation processes that lead to overall battery failure. These failure modes—manifesting as gas generation, thermal runaway, capacity fade, impedance growth, and electrolyte drying—not only degrade performance but also pose significant safety risks, including fire and explosion. Therefore, a deep and systematic understanding of electrolyte failure mechanisms, empowered by sophisticated characterization techniques, is essential for advancing the safety, longevity, and reliability of lithium-ion battery technology.

Electrolyte failure is rarely an isolated event; it is a consequence of intricate and often interconnected chemical and electrochemical reactions. The organic carbonate solvents, while excellent for ion transport, are thermodynamically metastable at the extreme potentials encountered at the electrode surfaces. On the anode, reduction reactions lead to the formation of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI), a passivating layer crucial for cycle life. An unstable or continually growing SEI, however, consumes active lithium and electrolyte, increasing impedance. Concurrently, oxidation reactions occur at the high-voltage cathode, leading to electrolyte decomposition, transition metal dissolution, and surface film formation. These processes are exacerbated by elevated temperatures, high states of charge, and the presence of impurities like trace water. Water hydrolyzes LiPF6, generating HF, which corrodes electrode materials and accelerates degradation. The collective outcome of these reactions is a transformed electrolyte: depleted in active components, enriched with decomposition products, and potentially generating significant gaseous species. Diagnosing this transformation requires a multi-faceted analytical approach, moving beyond simple performance metrics to probe the molecular-level changes occurring within the cell.

Fundamental physical properties of the electrolyte, namely ionic conductivity ($\sigma$) and viscosity ($\eta$), serve as primary indicators of its health and directly influence lithium-ion battery performance. Conductivity governs the cell’s internal resistance and power capability, while viscosity affects wetting, pore-filling, and ion transport kinetics. Their relationship is often approximated by the empirical Walden’s rule or more fundamentally linked through the Stokes-Einstein equation, considering the effective ionic radius ($r_i$):

$$

\sigma \propto \frac{1}{\eta} \quad \text{or} \quad D_i = \frac{k_B T}{6 \pi \eta r_i}

$$

where $D_i$ is the diffusion coefficient, $k_B$ is Boltzmann’s constant, and $T$ is temperature. Aging in a lithium-ion battery typically leads to solvent evaporation, salt decomposition, and polymeric product formation, increasing $\eta$ and decreasing $\sigma$. Accurate measurement of these properties in extracted electrolyte from failed cells, using calibrated viscometers and conductivity meters with correction for electrode polarization, provides the first tangible evidence of electrolyte degradation.

A more direct and critical manifestation of electrolyte failure is gas generation. Gassing can cause cell swelling, loss of electrical contact, accelerated degradation, and in severe cases, rupture. The gases originate from a multitude of reactions: reductive decomposition of solvents (e.g., EC to C2H4 and CO), oxidative decomposition at the cathode (producing CO2, CO), and reactions involving impurities. The table below summarizes common gas species and their associated formation pathways within a lithium-ion battery.

| Gas Species | Primary Formation Pathway | Typical Trigger/Condition |

|---|---|---|

| H2 | Reduction of trace H2O; Solvent/Additive reduction | Low anode potential; Presence of moisture |

| CO | Oxidative decomposition of carbonates; Incomplete reduction | High cathode potential (>4.3 V vs. Li/Li+) |

| CO2 | Oxidative decomposition of carbonates; Decarboxylation reactions; Reaction of Li2CO3 with HF | High voltage; High temperature; Surface impurities |

| C2H4 | Reductive ring-opening polymerization of EC | First cycle SEI formation on graphite |

| CH4, C2H6 | Further reduction of alkyl carbonates or ethers | Severe over-discharge or localized lithium plating |

Characterizing this gas evolution is crucial. Ex-situ analysis, primarily using Gas Chromatography (GC) coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) or selective detectors like Thermal Conductivity Detectors (TCD) and Flame Ionization Detectors (FID), provides quantitative composition data from failed cells. However, to capture the dynamic evolution of gases during operation, in-situ or operando techniques are indispensable. Online Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (OEMS) and Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (DEMS) allow for real-time monitoring of gaseous products as a function of voltage or time, directly linking specific electrochemical events (e.g., a voltage plateau) to the formation of a particular gas. This capability is vital for deconvoluting complex degradation pathways and evaluating the effectiveness of electrolyte additives designed to suppress gassing.

The most severe failure mode of a lithium-ion battery is thermal runaway, a positive feedback loop of heat generation leading to cell destruction. The electrolyte plays a central and dual role in this process: as a primary fuel and as a participant in exothermic reactions. The sequence often begins with the metastable SEI decomposing at temperatures around 80-120°C, exposing the anode to the electrolyte. This triggers violent exothermic reactions between the lithiated anode (e.g., LixC6) and the electrolyte solvents. The heat generated raises the temperature further, leading to separator meltdown (130-180°C), cathode decomposition releasing oxygen (>200°C), and finally, the combustion of the organic electrolyte itself in the presence of oxygen. The overall heat release ($Q_{total}$) can be modeled as the sum of reactions:

$$

Q_{total} = Q_{SEI} + Q_{Anode-El} + Q_{Sep} + Q_{Cathode} + Q_{Combustion}

$$

where $Q_{Anode-El}$ and $Q_{Combustion}$ are major contributors involving the electrolyte. Advanced calorimetric techniques are used to probe this behavior. Accelerating Rate Calorimetry (ARC) adiabatically tracks the self-heating of a cell to identify onset temperatures and measure total heat release. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) analyzes the reactivity of individual components (e.g., charged electrodes soaked in electrolyte) to quantify the enthalpy of specific reactions. Coupling ARC with gas analysis (e.g., ARC-MS) provides a holistic view, correlating the onset of gas venting (e.g., CO2, C2H4, PF3O from LiPF6 decomposition) with the rapid temperature rise characteristic of thermal runaway in a lithium-ion battery.

Beyond catastrophic events, the silent, cumulative degradation of the electrolyte composition—”aging”—is a primary cause of long-term capacity fade and impedance rise in lithium-ion batteries. This involves the depletion of the lithium salt (LiPF6), consumption of solvents and functional additives, and the accumulation of soluble and insoluble decomposition products. Analyzing this chemical evolution requires a suite of complementary techniques. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, particularly 1H, 19F, and 31P NMR, is powerful for identifying and quantifying organic and phosphorus-containing species. Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) is essential for detecting non-volatile, high-molecular-weight polymeric products that GC-MS cannot detect. Ion Chromatography (IC) is used to monitor anion concentrations (e.g., PF6–, F–, PO2F2–), while Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (ICP-OES/MS) tracks metal ions (Li+, Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+) dissolved from the cathode. A comprehensive aging analysis of a cycled lithium-ion battery electrolyte might reveal a decrease in EC and LiPF6 concentration, an increase in organophosphates and polycarbonates, and the presence of transition metals, all contributing to increased impedance and capacity loss.

The complexity of electrolyte failure necessitates moving beyond post-mortem analysis. Operando characterization techniques are revolutionizing our understanding by providing real-time, spatially resolved information under operating conditions. These methods allow us to observe degradation as it happens, establishing definitive cause-and-effect relationships.

- Operando Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (OEMS/DEMS): As mentioned, these techniques provide real-time gas analysis during cycling, critical for studying SEI formation, additive consumption, and high-voltage instability.

- Operando Pressure Measurements: Coupling a pressure sensor with a cell quantifies total gas evolution, complementing the compositional data from MS.

- Operando Spectroscopy: Techniques like Infrared (FTIR) and Raman spectroscopy can probe molecular structure changes in the electrolyte and at electrode interfaces. For example, operando FTIR can detect the formation of carbonyl-containing decomposition products like alkyl dicarbonates or the consumption of specific solvent molecules near the electrode surface.

- Operando Microscopy and Tomography: X-ray computed tomography (X-CT) and neutron imaging can visualize macroscopic changes like gas bubble formation, electrode deformation, and electrolyte wetting/drying in a working lithium-ion battery.

The synergy of multiple analytical techniques—a “multi-modal” approach—is often the key to unraveling complex failure mechanisms. For instance, correlating data from operando pressure measurements (total gas), OEMS (gas identity), post-mortem GC-MS (volatiles), NMR (non-volatiles), and ICP (metal dissolution) builds a complete picture of the degradation cascade. This approach can pinpoint whether capacity fade in a high-nickel lithium-ion battery is driven more by electrolyte oxidation at the cathode, salt depletion, or cross-talk from dissolved metals poisoning the anode.

The ultimate goal of failure analysis is not just diagnosis but prediction and prevention. This drives the development of advanced simulation and warning technologies. Physics-based and data-driven models can integrate the mechanistic understanding gained from the above techniques to predict cell lifetime and failure probability under various usage scenarios. Furthermore, early warning systems are being developed based on non-invasive signatures of incipient failure. These include:

- Detecting characteristic gas species (e.g., CO) using embedded micro-sensors before thermal runaway occurs.

- Monitoring changes in electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) signatures that indicate SEI overgrowth or contact loss.

- Analyzing the differential voltage ($dV/dQ$) or incremental capacity ($dQ/dV$) curves to detect subtle side reactions indicative of electrolyte degradation.

Implementing such diagnostics can enable fail-safe mechanisms or preventive maintenance, significantly enhancing the safety management of lithium-ion battery packs.

In conclusion, the electrolyte is both the lifeblood and a primary failure point of the lithium-ion battery. Its degradation through gassing, thermal decomposition, and chemical aging is a multi-step, interdependent process that dictates performance decay and safety hazards. Addressing these challenges requires a deep analytical toolbox. The future of lithium-ion battery electrolyte failure analysis lies in the sophisticated integration of operando and multi-modal characterization techniques, coupled with advanced simulation models. This integrated approach will accelerate the development of more robust, safer electrolytes and enable smart battery management systems capable of predicting and preventing failure, thereby unlocking the full potential of lithium-ion battery technology for a sustainable energy future.