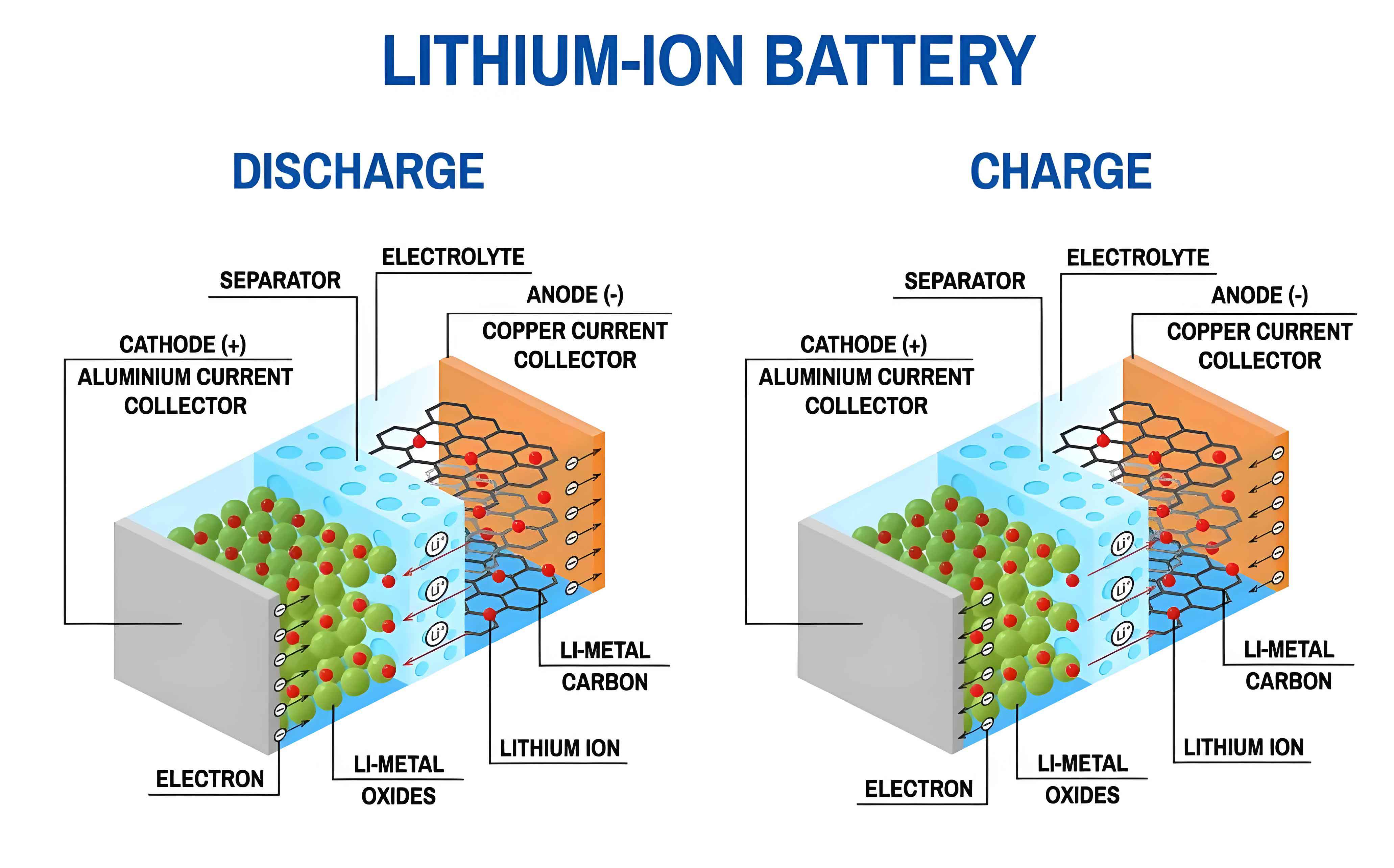

The relentless global shift towards electrification has cemented the lithium-ion battery as the cornerstone of modern energy storage technology. Its applications span from powering electric vehicles and portable electronics to stabilizing grids through large-scale energy storage systems. Within this electrochemical marvel, the cathode material is arguably the most critical component, dictating fundamental performance metrics such as energy density, cycle life, power capability, and safety. The intricate physical and chemical properties of these cathodes, coupled with the quality of their manufacturing processes, are primary determinants of the final battery’s efficacy and reliability. As demand surges and application scenarios become more severe—ranging from extreme fast-charging to operation in harsh climates—incidents of battery failure and performance degradation have become more frequent. A root cause analysis often reveals a critical gap: the lack of effective, holistic quality observation and dynamic management throughout the cathode material’s entire lifecycle. Traditional quality management systems, built on linear, siloed processes, are fundamentally ill-equipped to facilitate real-time data sharing across stages or enable proactive management of quality issues. In this context, Digital Twin technology emerges as a transformative paradigm. By creating a dynamic virtual representation of a physical object or process, a Digital Twin enables high-fidelity simulation, real-time monitoring, and intelligent prediction. This capability introduces a new dimension of “visibility, controllability, and traceability” to quality management. Therefore, constructing a full lifecycle quality management system for lithium-ion battery cathode materials, powered by Digital Twin technology, represents a pivotal step in evolving from reactive “post-mortem inspection” to proactive “whole-process optimization.” In this article, I will explore this objective, delineate its immense value, diagnose the prevailing challenges, and propose a systematic strategy for its implementation.

The imperative for such an advanced system stems from the complex, multi-stage journey of a cathode material. From precursor synthesis and calcination to coating, cell assembly, field operation, and eventual recycling, each phase generates vast amounts of data that are intrinsically linked to final performance. A failure in a vehicle’s battery pack might originate from a subtle inconsistency in the cathode’s precursor mixing months earlier—a connection nearly impossible to trace with conventional methods. The Digital Twin serves as the central nervous system to make these connections explicit and actionable.

1. The Imperative for a Paradigm Shift in Quality Management

The traditional approach to managing the quality of materials for the lithium-ion battery industry is predominantly focused on the manufacturing stage. Quality control checkpoints are established at the end of key production lines, such as after sintering or final sizing, relying on statistical sampling. This method suffers from significant latency; problems are identified only after a batch is produced, leading to costly scrap, rework, and potential supply chain disruptions. Moreover, it creates blind spots at the critical beginning (R&D and design) and end (field use and recycling) of the lifecycle. A cathode material’s performance is not defined solely in the factory; its electrochemical behavior is a function of its intrinsic design, the conditions of its use within a lithium-ion battery, and its interaction with other cell components over time. A holistic view is non-negotiable.

The Digital Twin paradigm addresses this by establishing a closed-loop, cyber-physical system. It is built upon several core technological pillars: the Internet of Things (IoT) for real-time data acquisition from equipment and sensors, high-fidelity multi-physics models that simulate material behavior, data analytics and machine learning for pattern recognition and prediction, and a unified data platform that serves as a “single source of truth.” This integrated framework allows for the continuous synchronization between the physical material flow and its digital shadow.

2. Value Proposition of a Digital Twin-Driven System

The implementation of a Digital Twin for managing the lifecycle quality of lithium-ion battery cathode materials delivers transformative value across multiple dimensions.

2.1 Enabling Transparent, Lifecycle-Wide Quality Information Flow

In conventional setups, data from R&D, production, testing, and field operation reside in isolated systems—LIMS, MES, ERP, and customer service databases. This fragmentation breaks the information continuum. A Digital Twin platform acts as a unified data integrator, creating a coherent digital thread that links every stage. For instance, the virtual model of a cathode material can encapsulate not just its final specification sheet, but its entire history: the lot numbers of its lithium carbonate and transition metal precursors, the time-temperature profile during its calcination, the particle size distribution (PSD) after milling, and its subsequent performance in half-cell and full-cell testing.

This transparency enables unprecedented traceability and collaborative improvement. When a cell manufacturer reports a higher-than-expected impedance increase in a specific batch of lithium-ion batteries, the Digital Twin can instantly trace back to the corresponding cathode material batch, review its synthesis parameters, and correlate them with the observed issue. Conversely, insights from field performance can be fed directly back into the R&D digital model to refine the next generation of material design. The value is summarized in the transition it enables:

| Traditional Siloed Approach | Digital Twin-Integrated Approach |

|---|---|

| Data locked in stage-specific systems (LIMS, MES). | Unified data fabric linking all lifecycle stages. |

| Problem identification is reactive and slow. | Proactive anomaly detection via model-data comparison. |

| Root cause analysis is manual and error-prone. | Automated, data-driven root cause tracing. |

| R&D iterations are slow and based on limited test data. | R&D is accelerated using field data and virtual DoE (Design of Experiments). |

2.2 Enhancing Process Control and Adaptive Response

The manufacturing of cathode materials like NMC (Lithium Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide) or LFP (Lithium Iron Phosphate) involves highly nonlinear processes sensitive to numerous parameters: precursor mixing homogeneity, sintering temperature and atmosphere, milling energy, etc. Minor deviations can lead to significant variations in critical properties like tap density, specific surface area, and cation ordering, ultimately affecting the consistency and performance of the lithium-ion battery.

A Digital Twin moves quality control from the lab table into the process itself. Real-time sensor data from production equipment (furnace temperatures, mixer torque, PSD analyzers) is continuously streamed into the virtual model. The model, calibrated with historical quality data, compares the actual process trajectory against the ideal “golden batch” profile. Using machine learning algorithms, it can predict the final material properties based on current process states and detect subtle deviations long before they result in out-of-spec material.

For example, consider the critical sintering process. The Digital Twin can monitor the temperature profile (\(T(t)\)) and atmosphere composition (\(O_2(t)\)) in real-time. The model can calculate a predicted crystallinity index (\(CI_{pred}\)) and compare it to the target. If a drift is detected, the system can either alert operators or, in a more advanced setup, automatically adjust the setpoints of the furnace controller to compensate. This creates a self-correcting, adaptive manufacturing line. The core feedback mechanism can be conceptually represented as:

$$ \Delta Q = f(P_{actual}, P_{target}, M, H) $$

Where:

- \(\Delta Q\) is the predicted quality deviation.

- \(P_{actual}\) is the vector of real-time process parameters.

- \(P_{target}\) is the vector of target process parameters.

- \(M\) is the material-specific digital twin model (e.g., linking temperature to grain growth).

- \(H\) is the historical data on parameter-quality correlations.

If \(|\Delta Q| > \epsilon\) (a predefined tolerance), a control action \(C_{action}\) is triggered.

2.3 Facilitating Proactive Failure Analysis and Liability Attribution

Failures in a lithium-ion battery often manifest after prolonged use, making root cause analysis exceedingly difficult. Was it a cathode impurity, an anode issue, electrolyte decomposition, or an operational abuse? The Digital Twin’s immutable record of the cathode’s lifecycle provides an invaluable forensic tool. Every action, parameter, and test result is timestamped and linked within the digital thread.

Suppose a fleet of electric vehicles exhibits abnormal capacity fade after 500 cycles. The OEM can query the Digital Twin platform of their cathode supplier, providing the specific material batch codes from the affected battery packs. The platform can instantly retrieve the complete manufacturing history of those batches and perform a comparative analysis against batches from batteries performing normally. It might reveal that the faulty batches shared a common anomaly: a slightly higher moisture content reading in the precursor feed, which the model can correlate with accelerated parasitic reactions at the cathode-electrolyte interface. This precise, data-backed attribution is far superior to traditional blame-shifting and enables targeted corrective actions.

| Failure Mode in Lithium-ion Battery | Potential Cathode-Related Root Cause | Digital Twin Traceability Data Point |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid Capacity Fade | Transition metal dissolution, structural degradation. | Sintering atmosphere log (oxygen partial pressure), precursor impurity analysis report. |

| High Internal Resistance | Poor particle conductivity, surface contamination. | Coating process parameters, post-coating washing log, specific surface area (SSA) trend data. |

| Voltage Plateau Shift | Lithium/nickel mixing in layered structures. | Precise sintering temperature profile data, cooling rate data from furnace controller logs. |

| Thermal Runaway Trigger | Cathode instability at high SOC/ temperature. | R&D simulation data on thermal stability, correlation with specific synthesis batch parameters. |

3. Prevailing Challenges in Current Practice

Despite the clear value proposition, the path to implementing a Digital Twin for lithium-ion battery cathode materials is fraught with significant obstacles rooted in legacy systems, organizational structures, and skill gaps.

3.1 Siloed Mindset and Fragmented Systems

The most pervasive challenge is the “silo effect.” Quality management is often a department, not a cross-functional philosophy. Data architecture mirrors this fragmentation. Laboratory Information Management Systems (LIMS) operate independently from Manufacturing Execution Systems (MES), which in turn are loosely coupled with Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) systems. Each system has its own data schema, often proprietary, making interoperability a major technical hurdle. This creates “data islands” where valuable information is trapped. For example, the correlation between a specific milling parameter in the MES and the resulting tap density measured in the LIMS requires manual export, reformatting, and analysis—a process too slow for real-time control. This fragmentation directly undermines the foundational requirement of a Digital Twin: a continuous, high-fidelity data stream.

3.2 Lack of Cross-Disciplinary Expertise

Building and maintaining an effective Digital Twin is a deeply interdisciplinary endeavor. It requires:

- Deep Materials Science Expertise: Understanding the electrochemistry and solid-state physics of cathode materials to build accurate models.

- Process Engineering Knowledge: Intimate knowledge of the actual manufacturing equipment and workflow to ensure the virtual model reflects reality.

- Data Science & Software Engineering Skills: Proficiency in data pipeline construction, machine learning algorithm development, and software architecture.

Currently, a glaring chasm exists between materials scientists/process engineers and data engineers/IT specialists. They speak different technical languages and have different priorities. A model built solely by data scientists may be mathematically elegant but physically nonsensical. Conversely, a concept described by a process engineer may be impossibly complex to codify. This talent gap is a critical bottleneck, leading to prolonged development cycles, poor model accuracy, and ultimately, project failure.

| Role/Discipline | Primary Focus | Common Gap in Digital Twin Context |

|---|---|---|

| Materials Scientist | Structure-property relationships, electrochemical mechanisms. | Limited understanding of data structures, algorithm limitations, and software development lifecycles. |

| Process Engineer | Equipment operation, throughput, yield, standard operating procedures (SOPs). | Unfamiliar with IoT sensor integration, real-time data streaming, and model predictive control concepts. |

| Data Scientist | Statistical analysis, machine learning model training, pattern recognition. | Lacks deep domain knowledge to interpret results meaningfully or to engineer relevant features from process data. |

| IT/Software Engineer | System infrastructure, database management, API development, cybersecurity. | Minimal understanding of the physical and chemical constraints of the manufacturing process being digitalized. |

3.3 Immaturity of Integrated Models and Feedback Loops

Many early Digital Twin initiatives focus on visualization and monitoring—creating a “digital dashboard.” While valuable, this is only the first step. The true power lies in the “closed loop”: the system’s ability to not just show data, but to analyze it, make a decision, and execute a corrective action autonomously or via a recommended action to a human operator. Developing the sophisticated multi-physics models that can accurately simulate complex processes like solid-state reaction kinetics during sintering, or the long-term degradation mechanisms of a cathode inside an operating lithium-ion battery, is a monumental scientific and engineering challenge. Furthermore, establishing robust, automated feedback channels from the field (e.g., from battery management system data in vehicles) back to the material design and production models remains an area of ongoing research and development.

4. A Strategic Framework for Implementation

To overcome these challenges and realize the full potential of a Digital Twin for cathode quality, a systematic, phased strategy is essential. The strategy must address technological, organizational, and human factors concurrently.

4.1 Architecting the Lifecycle System: From Linear to Circular

The first strategic shift is conceptual. The quality management system’s architecture must be redesigned from a linear pipeline into an integrated, circular lifecycle model. The Digital Twin is the platform that enables this circle. The key stages and their digital integrations are:

- Design & R&D: Use computational materials science and historical field data to simulate new cathode compositions. The performance predictions from these virtual prototypes become the initial “as-designed” digital twin.

$$ E_{cell}^{pred} = V_{cathode}(x, T) – V_{anode} – IR_{total}(S, \sigma_{eff}, …) $$

Where \(V_{cathode}\) is a function of lithium content \(x\) and temperature \(T\), modeled from first principles or empirical data. - Precursor & Synthesis: The digital model is instantiated with real batch IDs. IoT data from mixing, spray drying, and calcination continuously updates the twin, predicting final properties like crystallite size (\(L_{cryst}\)).

$$ L_{cryst} = k \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{RT}\right) \cdot t^{n} $$

Where \(k\), \(E_a\), \(n\) are model parameters fitted to historical data, \(R\) is the gas constant, \(T\) is sintering temperature, and \(t\) is time. - Cell Integration & Testing: The cathode twin is linked to the cell assembly process. Results from formation cycling and performance tests validate and refine the model.

- Field Operation: Data streams from Battery Management Systems (BMS) on state-of-health (SOH), resistance, and temperature feed back into the twin, creating a “living” model of degradation.

$$ Q_{loss}(t) = A \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{k_B T}\right) \cdot t^{0.5} + B \cdot (CRate) \cdot t $$

This empirical model for capacity loss \(Q_{loss}\) can be calibrated with field data. - Recycling & Feedback: Analysis of retired cathode material informs recyclability and provides direct feedback on failure modes, closing the loop to the R&D stage.

4.2 Building the Data Backbone: Integration and Standardization

A pragmatic, stepwise approach to data integration is necessary. A “big bang” replacement of all systems is rarely feasible. The strategy should center on:

- Establishing a Unified Data Platform (UDP): Implement a cloud-based or on-premise data lake/warehouse to act as the single repository for all lifecycle data.

- Developing Connectors & APIs: Create or procure standardized adapters for key systems (LIMS, MES, ERP, PLM, BMS cloud). Focus on pulling critical quality parameters (e.g., stoichiometry, impurity levels, PSD, density, electrochemical test results).

- Defining a Common Data Model: Enforce a standardized schema (e.g., based on ISA-95 or industry-specific ontologies) for representing materials, processes, and quality events. This is crucial for semantic interoperability.

- Prioritizing High-Value Data Streams: Start by integrating data from the most critical and variable processes, such as sintering and coating, to demonstrate quick wins.

4.3 Cultivating Cross-Functional Talent

Bridging the expertise gap is a long-term investment but a critical success factor. A multi-pronged approach is required:

| Initiative | Description | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Internal “T-shaped” Training | Train materials engineers in basic data literacy (Python, SQL) and data scientists in fundamental battery electrochemistry. | Creation of “translators” who can facilitate communication between domains. |

| Formation of Cross-Functional Pods | Organize project teams around specific Digital Twin modules (e.g., “Sintering Process Twin”). The team must include process experts, data scientists, and software developers co-located or in tight virtual collaboration. | Breaks down silos, ensures models are grounded in physical reality and are practically usable. |

| Strategic University Partnerships | Collaborate with universities to develop graduate programs in “Digital Materials Engineering” or “Battery Informatics,” combining core materials science with data engineering courses. | Builds a pipeline of future-ready talent with inherently interdisciplinary training. |

| Targeted Hiring & Upskilling | Actively recruit individuals with hybrid backgrounds and invest in upskilling current high-potential employees. | Accelerates the build-out of the core Digital Twin competency center. |

4.4 Evolving the Quality Feedback Mechanism

The final strategic pillar is to operationalize the intelligence of the Digital Twin. This means moving from monitoring to active quality control and continuous improvement.

- Real-Time Statistical Process Control (SPC) 2.0: Integrate the Digital Twin with control charts. Instead of just plotting a measured PSD, the system uses the twin’s model to predict the PSD based on upstream parameters. If the prediction and measurement diverge, it triggers an investigation into the cause (e.g., mill wear, precursor change) before spec limits are breached.

- Predictive Quality Analytics: Use machine learning on the integrated lifecycle data to build classifiers and regressors that predict final quality scores or failure probabilities early in the process. For instance:

$$ P(Fail) = \sigma\left(\beta_0 + \beta_1 \cdot \Delta T_{sinter} + \beta_2 \cdot [Li]/[TM] + \beta_3 \cdot SSA_{raw} + …\right) $$

Where \(\sigma\) is the logistic function, and \(\beta_i\) are coefficients learned from data. - Closed-Loop Adaptive Control: For well-understood process deviations, implement automatic adjustment rules. If the twin detects a rising trend in specific surface area linked to mill speed, it can automatically fine-tune the speed setpoint to bring the property back on target.

- Field-to-Factory Feedback Automation: Establish automated pipelines to ingest anonymized field performance data (from partnered OEMs). Use this data to retrain degradation models and update material design rules in the R&D Digital Twin, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement based on real-world lithium-ion battery performance.

5. Conclusion and Future Outlook

The journey towards ubiquitous, high-performance, and safe energy storage is intrinsically linked to the mastery of material quality. For the lithium-ion battery, this mastery hinges on the cathode. The complexity and extended lifecycle of these materials have rendered traditional, compartmentalized quality management systems inadequate. Digital Twin technology presents a paradigm-shifting solution, offering the framework to create a cohesive, intelligent, and proactive quality management ecosystem that spans from molecular design to end-of-life.

The construction of such a system is not merely an IT project; it is a strategic transformation that demands alignment across technology, process, and people. It requires dismantling data silos through integrated platforms, bridging disciplinary divides through targeted talent development, and shifting the quality philosophy from passive inspection to active, model-driven assurance. The rewards are substantial: dramatic reductions in scrap and rework, accelerated innovation cycles through virtual prototyping, unprecedented traceability for safety and liability, and ultimately, the production of more reliable, longer-lasting, and higher-performing lithium-ion batteries.

Looking ahead, the convergence of the Digital Twin with other Industry 4.0 technologies will amplify its impact. The integration of AI for autonomous model optimization, the use of blockchain for secure and immutable data logging across the supply chain, and advancements in multi-scale modeling from the atomic to the system level will make the Digital Twin even more powerful and precise. For any enterprise serious about leadership in the lithium-ion battery value chain, investing in the development of a full-lifecycle Digital Twin for cathode materials is no longer a futuristic concept—it is an urgent strategic imperative to secure quality, sustainability, and competitive advantage in the electrified age.