Perovskite solar cells have emerged as a leading technology in third-generation photovoltaics, with power conversion efficiencies exceeding 26%. These cells are typically fabricated from polycrystalline perovskite films, which inherently contain numerous defects. These defects, such as vacancies, interstitials, and anti-site disorders, act as non-radiative recombination centers, impairing charge carrier transport and reducing device performance. Chemical passivation has proven to be an effective strategy to mitigate these issues by forming chemical bonds or interactions with defect sites, thereby enhancing both efficiency and stability. This article explores the classification of defects in perovskite films and recent advancements in chemical passivation techniques, with a focus on coordination bonding and ionic bonding approaches. The integration of tables and formulas will summarize key concepts, and the discussion will emphasize the role of chemical passivation in advancing perovskite solar cell technology.

The crystal structure of perovskite materials follows the general formula ABX3, where A is an organic or inorganic cation (e.g., MA+, FA+, Cs+), B is a metal cation (e.g., Pb2+, Sn2+), and X is a halide anion (e.g., I−, Br−, Cl−). The structure consists of a cubic arrangement with BX64− octahedra, where A-site cations occupy the cube vertices. Defects in these polycrystalline films are categorized into shallow-level and deep-level defects. Shallow-level defects, with energy levels near the band edges, are primarily caused by vacancies of I− or MA+ and have low formation energies. Deep-level defects, located farther from band edges, include uncoordinated ions, interstitial defects, and anti-site disorders, which trap charge carriers and lead to significant non-radiative recombination. The defect density can be quantified using the formula for defect concentration: $$N_d = N_0 \exp\left(-\frac{E_f}{k_B T}\right)$$ where \(N_d\) is the defect density, \(N_0\) is the density of lattice sites, \(E_f\) is the formation energy, \(k_B\) is Boltzmann’s constant, and \(T\) is temperature. Understanding these defects is crucial for developing effective passivation strategies in perovskite solar cells.

Chemical passivation involves the use of materials that form covalent bonds, ionic bonds, or van der Waals interactions with defect sites. Coordination bonding, utilizing Lewis acids and bases, is a prominent method. Lewis acids, such as fullerene derivatives, accept electron pairs to passivate electron-rich defects like undercoordinated halides. For instance, phenyl-C61-butyric acid methyl ester (PCBM) interacts with I− vacancies, reducing recombination and improving film morphology. The passivation effect can be described by the equilibrium constant for Lewis adduct formation: $$K_{eq} = \frac{[Adduct]}{[Lewis\ Acid][Defect]}$$ where a higher \(K_{eq}\) indicates stronger passivation. Conversely, Lewis bases, containing lone-pair electrons (e.g., pyridine, amines), donate electrons to passivate electron-deficient defects like uncoordinated Pb2+. The binding energy (\(\Delta E_b\)) between a Lewis base and a defect can be calculated as: $$\Delta E_b = E_{complex} – (E_{passivator} + E_{defect})$$ where more negative values denote stable passivation. Bifunctional molecules, integrating both acidic and basic groups, offer synergistic passivation for multiple defect types. Table 1 summarizes common Lewis acid and base passivators used in perovskite solar cells.

| Passivator Type | Examples | Target Defects | Mechanism | Efficiency Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lewis Acid | PCBM, IPFB, TPFP | Uncoordinated I−, Pb-I anti-site | Electron acceptance | Up to 21.7% |

| Lewis Base | Pyridine, PVP, Urea | Uncoordinated Pb2+, Pb clusters | Electron donation | Up to 23.2% |

| Bifunctional | Indigo derivatives, Amines with C=O | Multiple defects | Synergistic bonding | Up to 25.02% |

Ionic bonding passivation employs cations or anions to neutralize charged defects. Cationic passivators, such as alkali metal ions (e.g., K+, Na+), fill A-site vacancies and form ionic bonds with undercoordinated halides. The passivation efficiency can be modeled using the electrostatic potential energy: $$U = \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{q_1 q_2}{r}$$ where \(q_1\) and \(q_2\) are charges, \(r\) is the distance, and \(\epsilon_0\) is the permittivity of free space. For example, K+ incorporation reduces iodine Frenkel defect formation energy, suppressing ion migration. Divalent cations (e.g., Ni2+, Cd2+) may substitute Pb2+ in the lattice, enhancing structural stability. Ammonium salts (e.g., R-NH3+X−) are versatile cationic passivators that can also induce low-dimensional perovskite phases, improving moisture resistance. Anionic passivators, such as Cl− or carboxylate ions, fill X-site vacancies and bond with uncoordinated Pb2+. The substitution energy for Cl− replacing I− is given by: $$\Delta E_{sub} = E_{Perovskite(Cl)} – E_{Perovskite(I)}$$ where negative values favor substitution. Table 2 compares ionic passivators and their effects on perovskite solar cell performance.

| Passivator Type | Examples | Target Defects | Key Effects | Stability Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cationic | K+, Na+, NH4+ | A-site vacancies, Uncoordinated I− | Reduced non-radiative recombination | High in humid conditions |

| Anionic | Cl−, I−, Carboxylates | X-site vacancies, Uncoordinated Pb2+ | Bandgap tuning, Morphology control | Improved thermal stability |

| Ammonium Salts | PEAI, OAI, Guanidinium | Multiple surface defects | Low-dimensional phase formation | Enhanced operational lifetime |

The effectiveness of chemical passivation can be quantified using parameters like the defect density of states (DOS). The DOS for a passivated system is often reduced, as described by: $$DOS(E) = \sum_i \delta(E – E_i)$$ where \(E_i\) are the energy levels of defects. Experimental techniques, such as photoluminescence spectroscopy, measure the passivation quality through carrier lifetime (\(\tau\)) enhancements: $$\frac{1}{\tau} = \frac{1}{\tau_{rad}} + \frac{1}{\tau_{non-rad}}$$ where \(\tau_{non-rad}\) decreases with effective passivation. For instance, passivation with alkali metals has shown to increase \(\tau\) from nanoseconds to microseconds, directly correlating with higher open-circuit voltage (\(V_{oc}\)) in perovskite solar cells. The \(V_{oc}\) loss due to defects can be expressed as: $$\Delta V_{oc} = \frac{k_B T}{q} \ln\left(1 + \frac{N_d}{n_i}\right)$$ where \(n_i\) is the intrinsic carrier concentration. By minimizing \(N_d\), chemical passivation approaches the theoretical efficiency limits of perovskite solar cells.

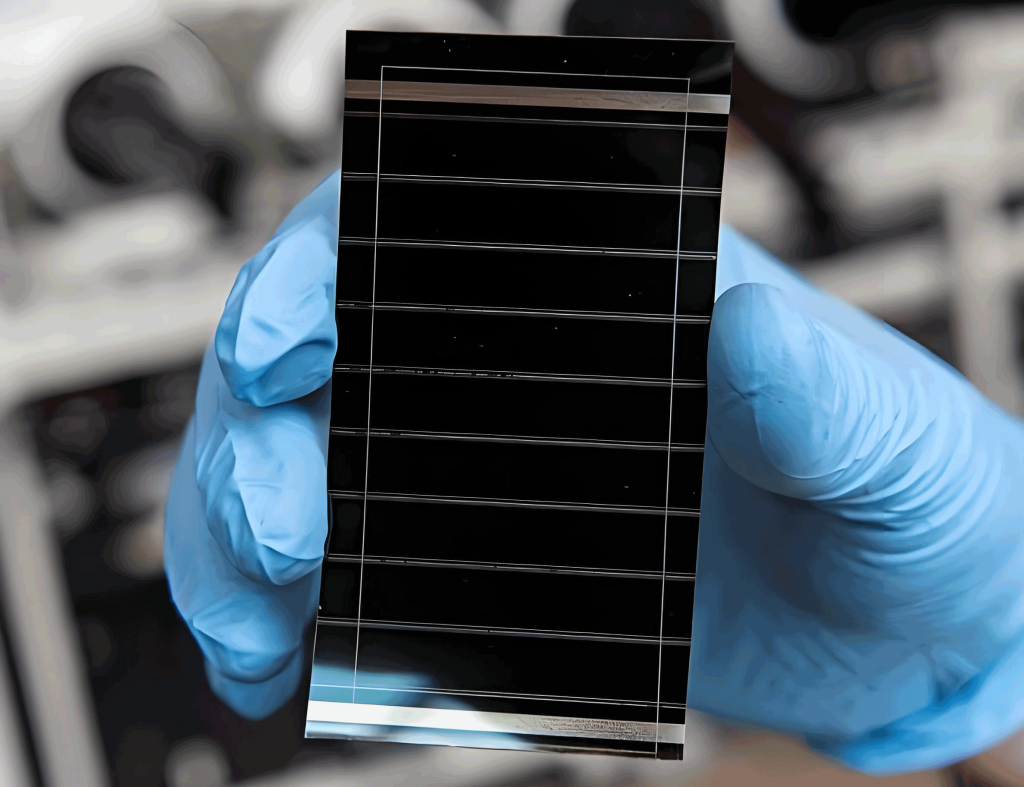

Future directions in chemical passivation for perovskite solar cells include the design of multifunctional passivators with optimized molecular configurations. Computational screening, using density functional theory (DFT), can predict binding energies and selectivity for specific defects. For example, the interaction energy between a passivator and a defect site can be computed as: $$E_{int} = E_{total} – E_{passivator} – E_{surface}$$ Additionally, the integration of passivation layers at both top and bottom interfaces of perovskite films is crucial, as defect densities are higher at interfaces. Scalable deposition methods, such as spray-coating or blade-coating, combined with in situ passivation, could enable large-scale production of high-efficiency perovskite solar cells. Stability under operational conditions, including light, heat, and humidity, remains a key challenge, and advanced passivators with hydrophobic moieties may further improve durability. In conclusion, chemical passivation is a vital strategy for achieving commercial viability of perovskite solar cells, and ongoing research promises to unlock new materials and mechanisms for superior performance.

In summary, chemical passivation addresses the intrinsic defects in perovskite solar cells through coordinated efforts involving Lewis acids/bases and ionic compounds. The continuous innovation in passivator design, coupled with a deeper understanding of defect chemistry, will drive the development of more efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. As the field progresses, the synergy between experimental findings and theoretical models will be essential for optimizing passivation protocols and achieving the full potential of perovskite-based photovoltaics.