In recent years, the rapid evolution of energy storage technologies has positioned lithium-ion batteries as a cornerstone for modern applications, from electric vehicles to portable electronics. The performance of a lithium-ion battery is intrinsically linked to the properties of its cathode materials, and among them, ternary layered oxides (often denoted as NCM or NCA) have garnered significant attention due to their high specific capacity and energy density. However, these materials face persistent challenges such as cation mixing, interfacial side reactions, and structural degradation during cycling, which limit their longevity and safety. In this comprehensive review, we delve into the recent advancements in modification strategies aimed at overcoming these hurdles, focusing on doping and coating techniques. We will systematically analyze how these approaches enhance electrochemical performance, employing tables and mathematical formulations to summarize key findings. The insights presented here are intended to guide future research and industrial applications in the realm of lithium-ion battery technology.

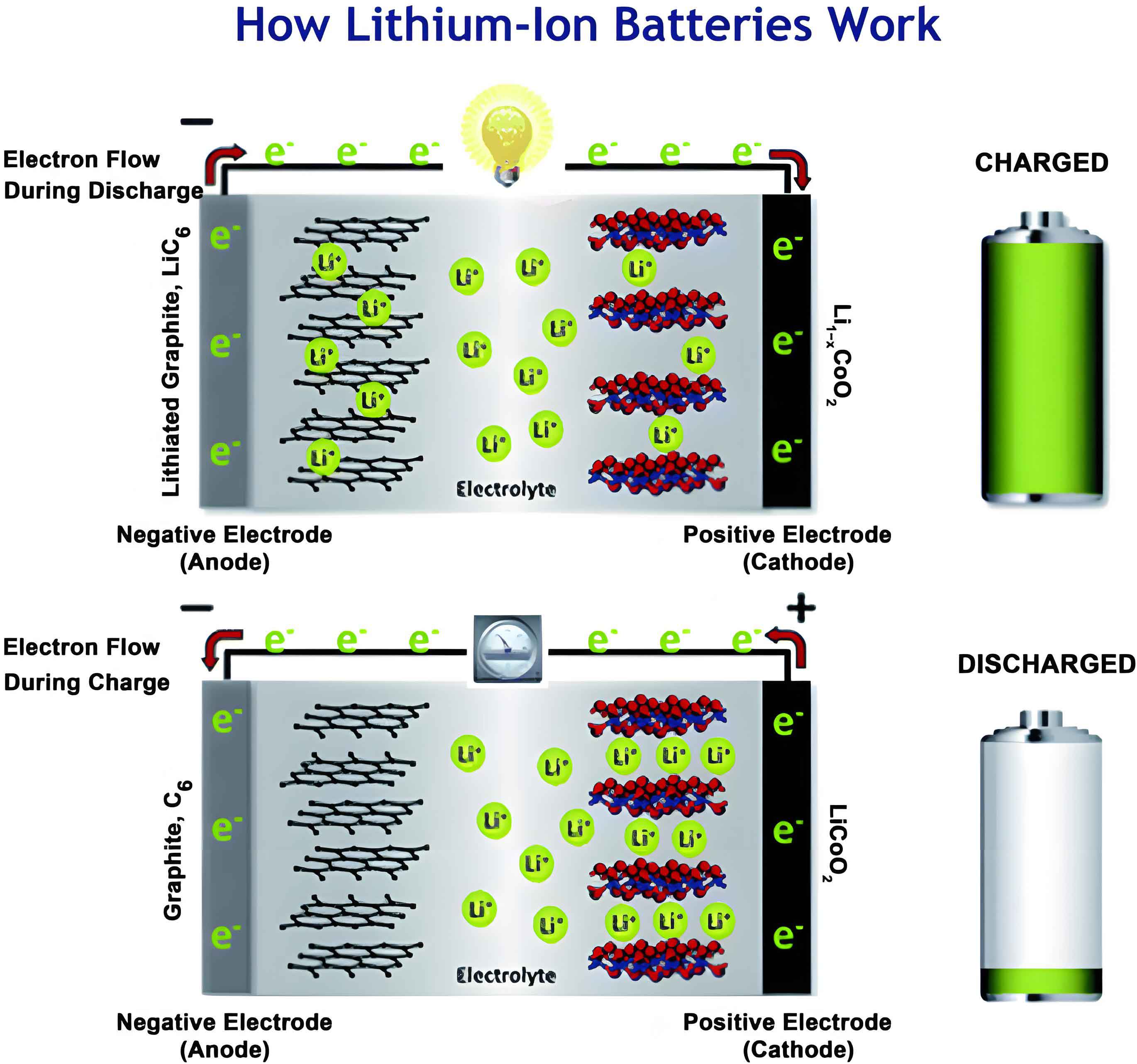

The fundamental operation of a lithium-ion battery relies on the reversible intercalation and deintercalation of lithium ions between the cathode and anode. For ternary cathode materials, the general formula is LiNixCoyMnzO2 (where x + y + z = 1), with each transition metal playing a distinct role. Nickel contributes to high capacity, cobalt enhances electronic conductivity and reduces cation disorder, and manganese stabilizes the structure. Despite these advantages, high-nickel content materials, in particular, suffer from rapid capacity fade due to phase transitions, oxygen release, and electrolyte decomposition at high voltages. To address these issues, researchers have developed various modification methods, which we explore in detail below. The ultimate goal is to achieve a lithium-ion battery with superior energy density, cycle life, and safety for widespread adoption.

One of the most effective ways to improve ternary cathode materials is through elemental doping. Doping involves introducing foreign atoms into the crystal lattice to stabilize the structure, enhance ionic conductivity, and suppress unwanted reactions. The choice of dopant is critical and often depends on factors such as ionic radius, valence state, and electronegativity. For instance, dopants with radii similar to Li+ (0.076 nm) can act as pillars in the lithium layer, preventing lattice collapse during cycling. The impact of doping can be quantified using parameters like the lithium-ion diffusion coefficient (DLi), which is crucial for rate performance. The diffusion coefficient can be approximated by the following equation derived from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy or galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT):

$$D_{Li^+} = \frac{4}{\pi \tau} \left( \frac{m_B V_M}{M_B A} \right)^2 \left( \frac{\Delta E_s}{\Delta E_t} \right)^2$$

where τ is the pulse time, mB is the active material mass, VM is the molar volume, MB is the molar mass, A is the electrode area, ΔEs is the steady-state voltage change, and ΔEt is the transient voltage change. This formula highlights how structural modifications can directly influence lithium-ion kinetics in a lithium-ion battery.

Single-ion doping has been extensively studied. Sodium (Na) doping, for example, can expand the interlayer spacing, facilitating lithium-ion diffusion. In one study, Na-doped Li1.2Na0.03[Ni0.2464Mn0.462Co0.0616]O2 showed an initial discharge capacity of 248.0 mAh/g at 0.1 C and retained 188.9 mAh/g after 110 cycles at 1 C. The improvement is attributed to reduced cation mixing and enhanced oxygen vacancy formation. Similarly, zirconium (Zr) doping at the lithium site in LiNi0.83Co0.12Mn0.05O2 led to a capacity retention of 94.6% after 200 cycles at 1 C, compared to 85.3% for the undoped material. Zirconium strengthens the TM-O bonds (where TM is transition metal), as described by the bond energy equation:

$$E_{bond} = k \cdot \frac{Z_+ Z_-}{r_+ + r_-}$$

where k is a constant, Z+ and Z– are the charges of the cation and anion, and r+ and r– are their radii. For Zr4+ with a high charge density, the bond energy with O2- is higher, stabilizing the lattice. Fluorine (F) doping is another promising approach, as it replaces oxygen to form strong Li-F bonds. In F-doped LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2, the initial coulombic efficiency increased to 90.74%, and capacity retention reached 88.1% after 150 cycles at 0.1 C. The enhancement can be modeled using the Nernst equation for the redox potential:

$$E = E^0 – \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q$$

where E is the cell potential, E0 is the standard potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday’s constant, and Q is the reaction quotient. F-doping shifts the potential, reducing side reactions. The table below summarizes key results from single-doping studies for lithium-ion battery cathodes.

| Dopant | Material Composition | Synthesis Method | Initial Discharge Capacity (mAh/g) | Capacity Retention (%) | Cycling Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na | Li1.2Na0.03[Ni0.2464Mn0.462Co0.0616]O2 | Solid-state reaction | 248.0 at 0.1 C | 188.9 after 110 cycles at 1 C | 2.0-4.8 V |

| Zr | LiNi0.83Co0.12Mn0.05O2 | Not specified | 173.9 at 1 C | 94.6 after 200 cycles at 1 C | 2.5-4.3 V |

| F | LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 | Co-precipitation | 171.8 at 0.1 C | 88.1 after 150 cycles at 0.1 C | 3.0-4.3 V |

| F | LiNi0.5Co0.2Mn0.3O1.99F0.01 | Co-precipitation | Not specified | 79.04 after 500 cycles at 10 C | 3.0-4.5 V |

| F | LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2 | Solid-state reaction | 201.0 at 0.1 C | 88.0 after 50 cycles at 1 C | 2.8-4.3 V |

Moving beyond single doping, co-doping strategies have emerged to harness synergistic effects. For instance, Sr and Zr co-doping in LiNi0.85Co0.10Mn0.05O2 resulted in a capacity retention of 99.4% after 200 cycles at 1 C. The larger Sr2+ ions act as pillars, expanding the O-Li-O layer spacing, while Zr4+ strengthens the framework. This dual approach mitigates microcrack formation and reduces interfacial impedance. The improvement in stability can be expressed through the Arrhenius equation for degradation kinetics:

$$k = A \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{RT}\right)$$

where k is the degradation rate constant, A is the pre-exponential factor, and Ea is the activation energy. Co-doping increases Ea for oxygen vacancy formation, slowing down capacity fade. Another example is Nb and Mg co-doping in LiMn0.5Fe0.5PO4, which enhanced the Mn2+/3+ redox kinetics and structural stability. The capacity retention reached 99% after 300 cycles at 0.5 C, demonstrating the effectiveness of co-doping in polyanion cathodes for lithium-ion batteries.

High-entropy doping represents a cutting-edge approach, where multiple elements are incorporated into the lattice to create configurational entropy-stabilized structures. In a high-entropy oxide fluoride, Lix(Co0.2Cu0.2Mg0.2Ni0.2Zn0.2)OxFx, the random distribution of cations and anions suppresses phase transitions and oxygen loss. This material exhibited a high initial capacity of 307 mAh/g at 20 mA/g and maintained over 170 mAh/g at 2 A/g. The stability can be attributed to the entropy effect, quantified by the Gibbs free energy equation:

$$\Delta G = \Delta H – T\Delta S$$

where ΔG is the change in Gibbs free energy, ΔH is enthalpy change, T is temperature, and ΔS is entropy change. High entropy (large ΔS) stabilizes the phase even with positive ΔH, making it resistant to degradation. For single-crystal NCM811 with high-entropy doping (e.g., Mg, Al, Zr, Nb), capacity retention improved to 80.79% after 300 cycles at 1 C. The enhanced oxygen electron density reduces lattice oxygen oxidation, a common failure mode in high-voltage lithium-ion battery operation.

Surface coating is another pivotal modification technique for ternary cathode materials. Coatings act as physical barriers, isolating the active material from the electrolyte to minimize parasitic reactions. Common coating materials include oxides, fluorides, and polymers. For example, polysiloxane-coated LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 showed a capacity retention of 91.5% after 120 cycles at 1 C, compared to 71.4% for the uncoated sample. The coating removes residual surface lithium compounds (e.g., LiOH, Li2CO3), which otherwise react with electrolytes to form HF and degrade performance. The protective effect can be modeled using Fick’s law of diffusion for electrolyte species:

$$J = -D \frac{\partial c}{\partial x}$$

where J is the flux, D is the diffusion coefficient, c is concentration, and x is distance. The coating reduces the flux of harmful species like HF toward the cathode surface. Similarly, LiF-coated LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 achieved 83.4% capacity retention after 100 cycles at 0.2 C, versus 65.9% for the bare material. The LiF layer also enhances lithium-ion transport due to its high ionic conductivity, as described by the equation for ionic conductivity (σ):

$$\sigma = n q \mu$$

where n is the charge carrier density, q is the charge, and μ is the mobility. The table below compares the performance of various coating materials in lithium-ion battery cathodes.

| Coating Material | Base Material | Synthesis Method | Initial Discharge Capacity (mAh/g) | Capacity Retention (%) | Cycling Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polysiloxane | LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 | Co-precipitation | 195.9 at 0.1 C | 88.7 after 100 cycles at 1 C | 3.0-4.3 V |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 | Co-precipitation | Not specified | 86.82 after 50 cycles at 1 C | 2.8-4.3 V |

| LiF | LiNi1/3Co1/3Mn1/3O2 | Co-precipitation | Not specified | 83.4 after 100 cycles at 0.2 C | 2.5-4.6 V |

| CeO2 | LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 | Co-precipitation | Not specified | 96.3 after 100 cycles at 1 C | 3.0-4.3 V |

To achieve even greater improvements, researchers have combined doping and coating into a synergistic modification strategy. For instance, Ce4+ doping coupled with CeO2 coating on LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 reduced cation mixing and expanded the (003) lattice spacing, leading to 96.3% capacity retention after 100 cycles at 1 C. The doping enhances bulk stability, while the coating protects the surface. Similarly, ZrO2 coating with Zr4+ doping suppressed the formation of surface lithium residues in air, addressing a key issue in large-scale production of lithium-ion battery materials. Another innovative approach involved in-situ formation of a Li2SO4 coating with sulfur doping on NCM, which minimized electrolyte decomposition and surface degradation. After 200 cycles, the modified material maintained significantly higher capacity than the pristine one. The synergy can be explained by the following general performance metric (P) for a lithium-ion battery cathode:

$$P = \alpha \cdot D_{Li^+} + \beta \cdot \sigma_{electronic} – \gamma \cdot R_{interface}$$

where α, β, and γ are weighting factors, DLi+ is lithium-ion diffusion coefficient, σelectronic is electronic conductivity, and Rinterface is interfacial resistance. Combined doping and coating optimize all three terms simultaneously.

In addition to experimental findings, theoretical models provide insights into modification mechanisms. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations often show that dopants like Zr and Al increase the formation energy of oxygen vacancies, thereby inhibiting oxygen release. The energy can be computed as:

$$E_{vac} = E_{defective} – E_{perfect} + \mu_O$$

where Evac is the oxygen vacancy formation energy, Edefective and Eperfect are the energies of the defective and perfect systems, and μO is the chemical potential of oxygen. For F-doping, the stronger Li-F bond energy (calculated using the Born-Landé equation) contributes to structural integrity:

$$E_{lattice} = \frac{N_A M Z^+ Z^- e^2}{4\pi \epsilon_0 r_0} \left(1 – \frac{1}{n}\right)$$

where NA is Avogadro’s number, M is the Madelung constant, Z+ and Z– are ion charges, e is electron charge, ε0 is vacuum permittivity, r0 is interionic distance, and n is the Born exponent. These equations underscore the atomic-level changes induced by modification.

Looking ahead, the future of ternary cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries lies in multi-faceted optimization. High-throughput screening and machine learning can accelerate the discovery of optimal dopant and coating combinations. Moreover, focusing on interface engineering—such as developing smart coatings that self-heal or adapt to voltage changes—will be crucial for long-cycle-life batteries. Sustainability aspects, like reducing cobalt content and using environmentally benign modifiers, are also gaining traction. For example, iron or titanium-based dopants could lower costs while maintaining performance. Another promising direction is the integration of modifications with advanced manufacturing techniques, such as dry electrode coating or 3D printing, to produce next-generation lithium-ion batteries with tailored properties.

In conclusion, the modification of ternary cathode materials through doping and coating has proven highly effective in enhancing the electrochemical performance of lithium-ion batteries. Single doping improves specific properties, co-doping offers synergistic stabilization, and high-entropy doping leverages configurational entropy for robustness. Surface coatings protect against interfacial degradation, while combined strategies address both bulk and surface issues. The continuous innovation in these areas, supported by theoretical modeling and advanced characterization, will drive the development of safer, longer-lasting, and higher-energy-density lithium-ion batteries. As demand for efficient energy storage grows, these modified ternary materials are poised to play a pivotal role in the global transition to renewable energy and electrified transportation.

To further illustrate the impact of modifications, we can consider the overall energy density (E) of a lithium-ion battery, which depends on the cathode capacity (C), voltage (V), and mass (m):

$$E = \frac{C \cdot V}{m}$$

Modifications that increase C and V while minimizing m (e.g., by reducing inactive components) directly boost E. For instance, F-doping can raise the operating voltage by stabilizing the lattice at high states of charge. Additionally, the cycle life (N) can be modeled as a function of degradation factors:

$$N = \frac{C_0 – C_{th}}{k \cdot t}$$

where C0 is initial capacity, Cth is threshold capacity, k is degradation rate, and t is time. Modifications that reduce k—such as coatings that suppress electrolyte decomposition—extend N significantly. These quantitative relationships highlight the importance of ongoing research in material modification for advancing lithium-ion battery technology.