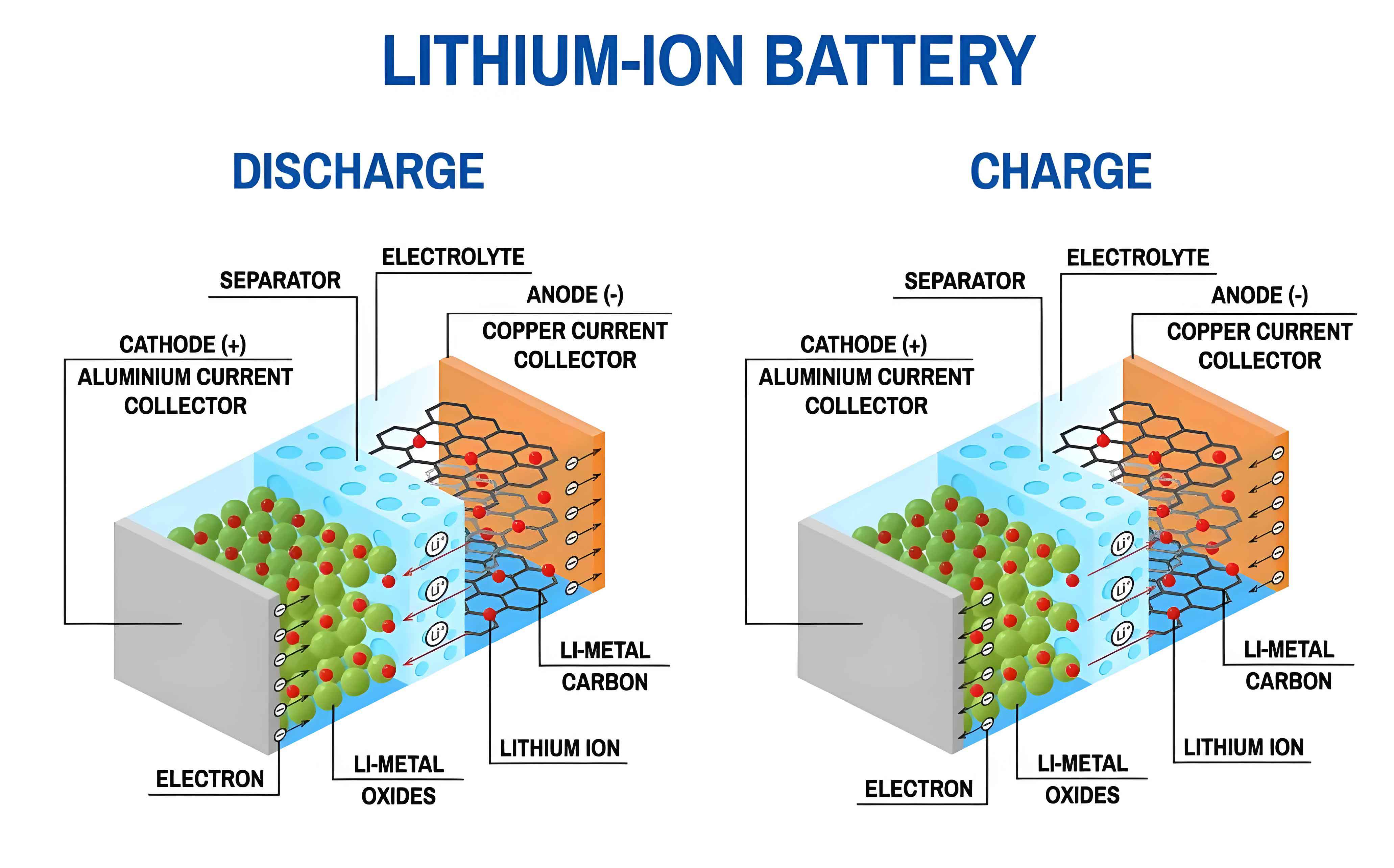

The pursuit of energy sustainability necessitates advanced energy storage solutions. Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have emerged as the cornerstone technology for portable electronics, electric vehicles, and grid storage due to their high energy density, long cycle life, and environmental friendliness compared to fossil-fuel-based systems. A critical yet often overlooked component within a lithium-ion battery is the polymeric binder. While constituting a small mass fraction, the binder is indispensable for maintaining the electrode’s structural and functional integrity. It creates a three-dimensional network that cohesively binds active material particles, conductive additives, and the current collector. The performance of the binder profoundly influences key electrochemical metrics of the lithium-ion battery, including cycle stability, capacity retention, coulombic efficiency, and aging rates.

The traditional benchmark, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), offers good adhesion and chemical stability but relies on toxic, flammable, and expensive organic solvents like N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP). This poses significant environmental, safety, and economic challenges for large-scale manufacturing. Consequently, developing high-performance, environmentally friendly, and cost-effective water-based binders is a pivotal strategy for the sustainable advancement of lithium-ion battery technology. This review systematically examines the major classes of aqueous binders, their modification strategies, application mechanisms, and future directions for industrialization.

1. Natural Polymer Binders

Derived from renewable resources like plants and marine life, natural polymer binders are inherently eco-friendly and biodegradable. Their molecular structures are rich in functional groups such as hydroxyl (-OH), carboxyl (-COOH), and amine (-NH2), which facilitate strong adhesion through hydrogen bonding and other polar interactions with electrode materials.

1.1 Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC)

CMC, a derivative of cellulose, is a linear, rigid polymer containing sodium carboxylate and hydroxyl groups. It is widely used as a thickener and binder, particularly in graphite anodes, due to its low cost and good dispersibility. A key challenge is its relatively low intrinsic adhesion strength. Common modification strategies include chemical grafting to introduce functional moieties. For instance, grafting dopamine onto CMC backbone enhances adhesion via catechol groups, significantly improving the cycling performance of silicon anodes. Other methods involve copolymerization with polyacrylic acid, plasma treatment, or pre-lithiation to boost ionic conductivity and stability.

1.2 Sodium Alginate (SA)

SA, extracted from brown algae, has a chemical structure similar to CMC but with a higher density of carboxylate groups. This provides stronger hydrogen bonding with materials like silicon, offering superior mechanical integrity and lower swelling in electrolytes. Cross-linking SA with agents like graphene oxide (GO) or calcium ions creates robust 3D networks, effectively buffering volume changes in high-capacity anodes and enhancing the longevity of the lithium-ion battery.

1.3 Chitosan (CS)

CS, obtained from chitin, contains abundant hydroxyl and amine groups. It demonstrates good adhesive properties and has gained attention for lithium-sulfur batteries due to its ability to adsorb polysulfides. Modification often focuses on improving its conductivity and mechanical flexibility, such as by grafting with catechol groups and compositing with carbon nanotubes to form an integrated conductive and adhesive network.

1.4 Other Natural Binders

Several other polysaccharides show promise:

- Guar Gum (GG): Higher hydroxyl content than SA, providing excellent mechanical properties and facilitating lithium-ion transport.

- Gum Arabic (GA): Acts as a dual-function binder and ion conductor, beneficial for electrodes with large volume expansion.

- Xanthan Gum (XG): Its unique double-helix structure with numerous side chains offers “millipede-like” strong electrostatic adhesion.

- β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD): Its conical cavity structure can host ions and molecules, useful for trapping polysulfides in Li-S batteries.

A general challenge for natural binders is batch-to-batch variability and sometimes insufficient performance for next-generation electrodes, necessitating chemical modifications that may increase cost.

| Binder | Source | Key Functional Groups | Main Advantages | Typical Modifications | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | Cellulose | -COO–Na+, -OH | Low cost, good dispersant, eco-friendly | Grafting (e.g., dopamine), copolymerization, pre-lithiation | Graphite anodes, Si anodes (with SBR) |

| Sodium Alginate (SA) | Brown Algae | -COO–Na+, -OH | High carboxyl density, strong adhesion, low swelling | Cross-linking with Ca2+, GO, or polymers | Si anodes, high-volume-change materials |

| Chitosan (CS) | Chitin | -NH2, -OH | Biodegradable, polysulfide adsorption | Sulfonation, grafting, composite with conductive materials | Li-S battery cathodes, Si anodes |

| Guar Gum (GG) | Guar Bean | -OH | High hydroxyl content, good ion transport | Cross-linking, blending | Si anodes, LTO anodes |

2. Synthetic Water-Based Polymer Binders

Synthetic binders offer precise control over molecular weight, architecture, and functionality through controlled polymerization. They can be tailored for specific electrode requirements, offering superior consistency and performance tunability compared to their natural counterparts.

2.1 Non-Conductive Synthetic Binders

2.1.1 Polyacrylic Acid (PAA) and Derivatives

PAA, with its high density of carboxylic acid groups, forms strong hydrogen bonds with active materials, providing excellent adhesion. However, its high rigidity and brittleness can be detrimental for electrodes undergoing large volume changes. Advanced modification strategies are crucial:

- Cross-linking & Dynamic Networks: Creating covalently or ionically cross-linked networks (e.g., with tannic acid or boronic esters) enhances mechanical strength and introduces self-healing properties, vital for silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries.

- Biomimetic & Energy-Dissipating Designs: Inspired by biological structures like titin, binders with gradient hydrogen bonding or sliding polyrotaxane units can efficiently dissipate stress during cycling, as described by the following relationship for energy dissipation (U):

$$ U = \int_{0}^{\epsilon} \sigma(\epsilon) \, d\epsilon $$

where $\sigma$ is stress and $\epsilon$ is strain. A binder with a high U value can absorb more mechanical energy from volume changes.

- Functionalization for Ion Transport: Copolymerizing AA with ionic monomers like 2-acrylamido-2-methylpropane sulfonic acid (AMPS) introduces sulfonate groups (-SO3–), creating pathways for rapid lithium-ion conduction, which lowers electrode impedance and improves rate capability.

2.1.2 Polyethylene Oxide (PEO)

PEO is renowned for its ability to solvate lithium salts, making it a prime candidate for solid polymer electrolytes. As a binder, its flexible chains and ether oxygens facilitate Li+ transport. Its high crystallinity, however, limits ionic conductivity at room temperature. This is often addressed by complexing with lithium salts (e.g., LiClO4) to reduce crystallinity, forming a gel-like conductive binder.

2.1.3 Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)

PVA, rich in hydroxyl groups, provides good adhesion but often lacks the mechanical robustness needed alone. High molecular weight PVA has shown superior adhesion to graphite compared to PVDF. It is frequently used in composite or cross-linked forms to enhance performance.

2.1.4 Polyimide (PI) and Polyurethane (PU)

PI offers exceptional thermal stability, mechanical strength, and electrochemical stability. Water-soluble PI precursors (polyamic acids) can be processed in aqueous slurry and later imidized. Ionic-conductive PI binders, incorporating sulfonimide lithium groups, enhance both adhesion and Li+ transport in cathodes.

Waterborne Polyurethane (WPU) is highly designable, with tunable soft and hard segments governing its elasticity and strength. Cross-linked WPU networks with ionic-conductive polyether segments can simultaneously provide robust mechanical support, inhibit polysulfide shuttling in Li-S batteries, and promote ion conduction, representing a multifunctional binder solution.

2.1.5 Styrene-Butadiene Rubber (SBR)

SBR latex provides excellent elasticity and adhesion but poor stability during high-shear mixing and weak bonding to current collectors. It is almost exclusively used in combination with CMC, where CMC acts as a thickener/dispersant and SBR provides the primary elastic bonding. Grafting PAA onto SBR (PAA-g-SBR) improves its compatibility with other polymeric binders and enhances the overall mechanical properties of the composite electrode in a lithium-ion battery.

| Binder | Key Features | Typical Challenge | Common Modification Strategies | Target Electrode |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyacrylic Acid (PAA) | High adhesion, rich -COOH groups | Brittle, poor stress dissipation | Cross-linking, copolymerization with ionic/elastic monomers, biomimetic designs | Si, SiOx, Sn anodes |

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | High Li+ solvation, flexible chain | High crystallinity at room T | Complexation with Li salts, copolymerization, cross-linking | Solid-state electrolytes, composite electrodes |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | High -OH content, good film formation | Moderate adhesion, water sensitivity | Use of high MW PVA, cross-linking, blending | Graphite anodes |

| Polyimide (PI) | Exceptional thermal/mechanical stability | Processing requires precursor (PAA) | Synthesis of ionic-conductive diamine monomers, aqueous processing | High-voltage cathodes, Si anodes |

| Waterborne PU (WPU) | Tunable elasticity/strength, good adhesion | Long-term electrochemical stability | Cross-linking, incorporating ionic/polar segments | Li-S cathodes, elastic electrodes |

| SBR | High elasticity, good particle binding | Shear instability, poor Cu adhesion | Grafting (e.g., PAA-g-SBR), use with CMC, cross-linking | Graphite anodes (with CMC) |

2.2 Conductive Synthetic Binders

These binders possess intrinsic electronic conductivity, potentially reducing or eliminating the need for separate conductive carbon additives, thereby increasing the energy density of the lithium-ion battery. The challenge lies in making them water-processable while maintaining good adhesion and mechanical properties.

2.2.1 PEDOT:PSS

Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):poly(styrene sulfonate) is a commercially available, water-dispersible conductive polymer complex. PSS acts as both a dopant and dispersant. While offering good conductivity, pristine PEDOT:PSS films can be brittle. Modifications include blending with elastic polymers like PEG or polyurethane to improve mechanical resilience and adhesion, or compositing with tannic acid to enhance stability in cathode applications.

2.2.2 Polyaniline (PANI), Polypyrrole (PPy), and Polyfluorene (PF)

These $\pi$-conjugated polymers require functionalization for water solubility and enhanced performance in lithium-ion battery electrodes.

- PANI: Often doped with protonic acids (e.g., camphorsulfonic acid) or sulfonated to become water-soluble. It can be grafted onto chitosan to combine conductivity with good adhesion for silicon anodes.

- PPy: Can be synthesized or composited in aqueous media using polyelectrolytes like PSS. Composites with phosphazene derivatives have shown promise as cathode binders.

- PF (n-type): Typically has lower conductivity than p-type polymers. Doping efficiency can be dramatically improved via coupled reaction mechanisms. Water solubility is achieved by grafting hydrophilic side chains (e.g., polyethylene glycol), though a balance with conductivity must be struck.

The electronic conductivity ($\sigma_e$) of these polymers is a key parameter, often following a power-law relationship with doping level:

$$ \sigma_e \propto (p – p_c)^t $$

where $p$ is the doping concentration, $p_c$ is the percolation threshold, and $t$ is a critical exponent.

3. Inorganic Binders

An emerging class, inorganic binders offer exceptional thermal stability, non-flammability, and high modulus. They are typically used in aqueous solutions or dispersions.

3.1 Silicate-Based Binders

Materials like lithium polysilicate (Li2Si5O11) or sodium metasilicate (Na2SiO3nH2O) form rigid, glass-like networks. Their structural similarity to silicon oxides promotes strong bonding with Si-based anodes. They can provide excellent mechanical support but may be too brittle. Strategies involve forming organic-inorganic hybrids, e.g., blending silicate solutions with PVA, to combine rigidity with some elasticity.

3.2 Phosphate-Based Binders

Polyphosphates like ammonium polyphosphate (APP) or aluminum polyphosphate are particularly attractive for lithium-sulfur batteries. The P-O bonds have strong affinity for lithium polysulfides, effectively anchoring them and suppressing the shuttle effect. Furthermore, they impart intrinsic flame retardancy to the electrode, enhancing the safety of the lithium-ion battery.

3.3 Borate-Based Binders

Borates (e.g., sodium tetraborate) can cross-link with hydroxyl-rich polymers like sodium alginate via esterification, forming a robust 3D network (Alg-SB). This significantly improves the mechanical strength and cycling stability of silicon anodes. Lithium borate (LiBO2) can also act as a pre-lithiation agent to compensate for initial irreversible capacity loss.

| Binder Class | Examples | Key Characteristics | Primary Function/Mechanism | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silicate | Li2Si5O11, Na2SiO3 | High rigidity, thermal stability, Si-O-Si network | Strong mechanical support, ion conduction channels | Si anodes, coated graphite anodes |

| Polyphosphate | (NH4PO3)n (APP), Al polyphosphate | Polysulfide affinity, flame retardancy | Chemisorption of LiPS, thermal barrier | Li-S battery cathodes |

| Borate | Na2B4O7, LiBO2 | Cross-linking agent, Lewis acid sites | Forms ester bonds with -OH polymers, enhances Li+ transport | Cross-linker for alginate/Si anodes, pre-lithiation |

4. Summary and Perspectives

The development of high-performance aqueous binders is central to the green manufacturing of lithium-ion batteries. Significant progress has been made across natural, synthetic, and inorganic binder families, each with distinct advantages and challenges. Future research and industrialization efforts should focus on the following directions:

1. Natural Polymers: The priority is to overcome batch variability and achieve performance consistency at scale. Green modification techniques (enzymatic, photocatalytic) and the exploration of abundant biopolymers like lignin are promising paths to low-cost, sustainable binders that align with carbon neutrality goals.

2. Synthetic Polymers (PAA focus): PAA remains a leading candidate due to its design flexibility. The future lies in bio-based acrylic acid production to enhance sustainability. Research should continue on advanced molecular designs integrating self-healing, high ionic conductivity, and optimal viscoelasticity to manage electrode stresses.

3. Conductive Polymers: The key is to lower production costs and improve water-based processing for robust, adhesive films. Hybrid strategies, combining small amounts of conductive polymers with low-cost primary binders, may offer a balanced solution for creating integrated conductive networks without sacrificing processability or cost.

4. Inorganic Binders: The most promising avenue is the development of inorganic-organic hybrid binders. These composites aim to harness the high modulus, thermal stability, and unique chemical functionalities (e.g., polysulfide trapping) of inorganic components while incorporating organic segments for elasticity and better interfacial adhesion, creating a new generation of multifunctional binders for the most demanding lithium-ion battery applications.

In conclusion, the transition to aqueous binders is not merely a solvent substitution but an opportunity for molecular-level innovation. Through strategic material design and cross-disciplinary collaboration, aqueous binders will play a pivotal role in enabling safer, more sustainable, and higher-performance energy storage systems.