In my research, I focus on the mechanical safety of lithium-ion batteries, which are critical for electric vehicles. The increasing demand for high-energy-density lithium-ion batteries necessitates rigorous safety assessments, particularly under mechanical abuse scenarios such as crushing, impact, and collision. This study aims to experimentally determine the safety limits of a specific prismatic lithium-ion battery under different indentation conditions, considering factors like indenter diameter and state of charge (SOC). The findings provide essential insights for battery pack design and safety simulation validation.

The safety of lithium-ion batteries is paramount, as mechanical deformation can lead to internal short circuits, thermal runaway, and catastrophic failure. My investigation involves systematic crushing tests on three orthogonal faces of a lithium-ion battery cell, employing indenters of different diameters and varying SOC levels. I meticulously analyze the force-voltage-temperature interplay during crushing to elucidate failure mechanisms and establish safety thresholds. This comprehensive approach helps in understanding how loading conditions affect the integrity of a lithium-ion battery.

1. Introduction and Background

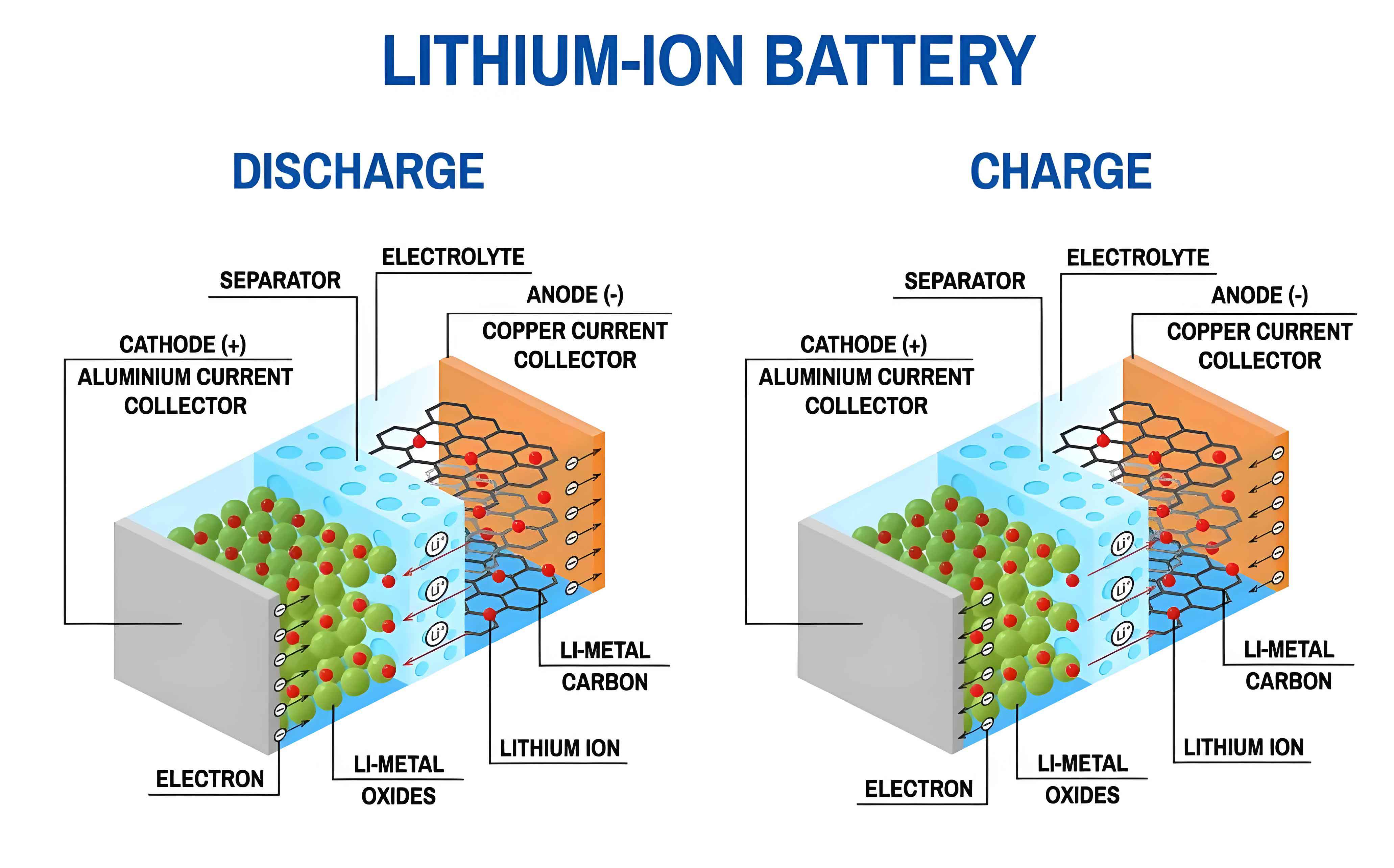

The rapid adoption of electric vehicles has escalated the need for reliable and safe lithium-ion batteries. Mechanical integrity is a crucial aspect, as real-world incidents like collisions, road debris impacts, and crushing can compromise the battery system. A lithium-ion battery’s response to mechanical stress is complex, involving multi-physics interactions between its components: the casing, electrodes, separator, and electrolyte. When a lithium-ion battery is subjected to indentation, the mechanical load can cause casing rupture, separator damage, and internal short circuits, potentially triggering thermal runaway. Therefore, quantifying the safety limits of a lithium-ion battery under various crushing conditions is vital for engineering robust battery packs.

Previous studies have explored mechanical abuse of lithium-ion batteries, but gaps remain in understanding the precise effects of indenter geometry and SOC on failure thresholds for prismatic cells. My work addresses this by conducting a cross-factorial experiment, examining the large face, side face, and bottom face of a lithium-ion battery cell. I employ two indenter diameters (25 mm and 50 mm) and three SOC levels (2%, 50%, and 100%) to simulate different impact scenarios. The primary objective is to determine the maximum displacement before failure for each configuration, thereby defining the safety limit. This knowledge directly informs the design of protective structures in battery packs and aids in calibrating computational models for crash safety.

The core of my methodology is the simultaneous measurement of crushing force, cell voltage, and surface temperature during indentation. This triad of data reveals the dynamic failure process of a lithium-ion battery. I hypothesize that indenter diameter significantly influences the safety limit due to stress distribution, while SOC may affect the severity of failure but not necessarily the initial mechanical threshold. Through detailed post-mortem analysis, I correlate external observations with internal damage to identify failure sequences. The ultimate goal is to establish a reliable database for the safety performance of this lithium-ion battery type under mechanical loading.

2. Experimental Methodology

I selected a commercial prismatic lithium-ion battery cell with a nickel-cobalt-manganese (NCM622) cathode and graphite anode. The nominal voltage is 3.7 V, with a full-charge voltage of 4.22 V. The cell dimensions are standardized, and for consistency, I ensured thickness variations in the crushing direction were within ±0.3 mm. The lithium-ion battery cell’s internal structure consists of stacked electrodes and separators, oriented differently relative to each face.

The crushing apparatus is a precision indentation machine capable of controlled displacement at a constant speed of 6 mm/min. It is equipped with a load cell (range: 0.05–300 kN), voltage probes (accuracy: 0.001 V), and thermocouples (accuracy: 0.1 °C). I defined three crushing faces: the large face (perpendicular to the x-axis, corresponding to the broad side of the electrode stack), the side face (perpendicular to the y-axis, the narrow side), and the bottom face (perpendicular to the z-axis, the end of the stack). For side and bottom face tests, I used fixtures to simulate constrained conditions akin to a battery module.

Each lithium-ion battery cell was prepared at the target SOC (2%, 50%, or 100%) using a standard charger-discharger. Voltage leads were attached to the terminals, and a thermocouple was secured with insulation tape near the indentation point. The indenter was aligned with the geometric center of the chosen face. Testing proceeded until a failure criterion was met: voltage drop, casing rupture, leakage, temperature rise, fire, or explosion. I adopted an iterative approach to pinpoint the safety limit. For instance, if a lithium-ion battery cell showed casing rupture at 10 mm displacement, the next test on a similar cell would stop at 8–9 mm to find the threshold where no failure occurs. Each test condition was repeated at least three times to ensure statistical reliability.

The data acquisition system recorded force, voltage, and temperature in real-time. I initiated crushing remotely, monitoring the responses until termination. Post-test, I visually inspected the lithium-ion battery cell and, for select samples, performed disassembly to examine internal damage. This holistic methodology allows me to capture the nuanced behavior of a lithium-ion battery under mechanical stress.

3. Theoretical Considerations and Formulations

To contextualize the experimental results, I consider basic mechanical and thermal models. The crushing process involves complex material deformation, but simplified models can offer insights. The force-displacement relationship for a lithium-ion battery cell under indentation can be approximated using energy principles. The work done by the indenter is absorbed by the plastic deformation of the casing and the internal components.

For a spherical indenter, the contact force \(F\) can be related to displacement \(\delta\) using Hertzian contact theory for initial elastic deformation, but for large plastic deformation, empirical models are more suitable. I express the mean crushing pressure \(P_m\) as:

$$ P_m = \frac{F}{A_c} $$

where \(A_c\) is the contact area. For a spherical indenter of diameter \(D\), the contact area increases with displacement. The safety limit, defined as critical displacement \(\delta_c\), may correlate with the energy absorption capacity \(E_a\) of the lithium-ion battery:

$$ E_a = \int_0^{\delta_c} F \, d\delta $$

This energy absorption until failure is a key metric for comparing different conditions.

Regarding thermal aspects, if a lithium-ion battery experiences an internal short circuit, the heat generation rate \(\dot{Q}\) can be modeled using Joule heating and electrochemical reactions. A simplified heat balance for the lithium-ion battery is:

$$ m C_p \frac{dT}{dt} = \dot{Q} – h A_s (T – T_{\infty}) $$

where \(m\) is mass, \(C_p\) is specific heat, \(T\) is temperature, \(h\) is heat transfer coefficient, \(A_s\) is surface area, and \(T_{\infty}\) is ambient temperature. The heat generation \(\dot{Q}\) may spike due to short circuit resistance \(R_{sc}\):

$$ \dot{Q} = I_{sc}^2 R_{sc} $$

where \(I_{sc}\) is the short-circuit current. This model explains the rapid temperature rise observed during thermal runaway in a lithium-ion battery.

Furthermore, the voltage drop during failure relates to the internal resistance increase. The open-circuit voltage \(V_{oc}\) of a lithium-ion battery drops when electrodes short. The instantaneous voltage \(V(t)\) under load can be expressed as:

$$ V(t) = V_{oc} – I(t) R_{int}(t) $$

where \(R_{int}(t)\) increases as damage propagates. Monitoring \(V(t)\) and \(T(t)\) simultaneously provides clues about the failure mode of the lithium-ion battery.

4. Results and Data Analysis

4.1 Observed Failure Modes

During my experiments, the lithium-ion battery exhibited distinct failure modes. For the large face indentation, failures often involved casing rupture followed by fire or explosion, especially at high SOC. For the side and bottom faces, casing rupture with electrolyte leakage was more common, with occasional fires. I categorize the failure modes as:

- Casing Rupture and Leakage: The aluminum housing fractures, causing electrolyte leakage without significant thermal event.

- Internal Short Circuit with Thermal Runaway: Separator damage leads to electrode contact, causing voltage drop, temperature spike, and sometimes fire or explosion.

- Combined Failure: Casing rupture precedes or accompanies thermal runaway, with flames ejecting from the breach.

Post-mortem dissection revealed that for the large face, the separator directly under the indenter often melted or tore, indicating severe internal shorting. For side and bottom faces, the separator tended to remain intact despite casing deformation, explaining the lower incidence of fire. This underscores how the orientation of the lithium-ion battery’s internal layers influences failure propagation.

4.2 Force-Voltage-Temperature Profiles

I captured synchronized force, voltage, and temperature curves for each test. Representative plots for near-threshold failures are synthesized below. The force typically rises monotonically until a peak, then may drop sharply if casing fails or gradually if deformation stabilizes. Voltage remains stable until internal shorting occurs, then plummets. Temperature lags slightly behind voltage drop due to thermal inertia, then rises rapidly during thermal runaway.

For a lithium-ion battery crushed on the large face with a 25 mm indenter at 100% SOC, failure occurred at 11 mm displacement. The force reached approximately 25 kN before a sharp drop. Voltage began declining at 10.5 mm, falling to near zero within seconds. Temperature started rising from 25°C to over 400°C in about 30 seconds. In contrast, for the same lithium-ion battery at 2% SOC, the force profile was similar, but voltage drop was less abrupt, and temperature peaked around 200°C. This suggests SOC affects the severity of thermal response but not the initial mechanical failure point.

For side face indentation with a 50 mm indenter, the lithium-ion battery showed casing rupture at 10 mm without voltage drop or temperature rise. The force curve exhibited small fluctuations due to buckling instabilities, not necessarily failure. These observations highlight that voltage and temperature changes are reliable indicators of internal shorting in a lithium-ion battery, whereas force anomalies alone may not signify catastrophic failure.

4.3 Safety Limit Determination

I define the safety limit as the maximum indentation displacement before any failure criterion is met. Through iterative testing, I established the thresholds for each face, indenter diameter, and SOC. The results are consolidated in Table 1.

| Crushing Face | Indenter Diameter (mm) | State of Charge (SOC) | Safety Limit (mm) | Primary Failure Mode at Limit+1 mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Face | 25 | 2% | 10 | Casing rupture, leakage |

| 50% | 10 | Fire/explosion | ||

| 100% | 10 | Fire/explosion | ||

| 50 | 2% | 13 | Casing rupture, leakage | |

| 50% | 13 | Fire/explosion | ||

| 100% | 13 | Fire/explosion | ||

| Side Face | 25 | 2% | 7 | Casing rupture, leakage |

| 50% | 7 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| 100% | 7 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| 50 | 2% | 8-9 | Casing rupture, leakage | |

| 50% | 8-9 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| 100% | 8-9 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| Bottom Face | 25 | 2% | 19 | Casing rupture, leakage |

| 50% | 19 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| 100% | 19 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| 50 | 2% | 20 | Casing rupture, leakage | |

| 50% | 20 | Casing rupture, leakage | ||

| 100% | 20 | Fire/explosion |

The data shows that for a given face and indenter diameter, the safety limit is consistent across SOC levels. For example, the large face safety limit is 10 mm for 25 mm indenter and 13 mm for 50 mm indenter, regardless of SOC. This indicates that the mechanical integrity of the lithium-ion battery, defined by casing and internal structure strength, is independent of charge state at the point of initial failure.

However, the failure mode severity is SOC-dependent. At high SOC (50% and 100%), a lithium-ion battery is more prone to thermal runaway after casing breach, leading to fire or explosion. At low SOC (2%), the same mechanical damage often results only in leakage. This is because the energy stored in the lithium-ion battery is lower, reducing the intensity of electrochemical reactions during short circuit.

Comparing faces, the bottom face has the highest safety limit (19-20 mm), followed by the large face (10-13 mm), and then the side face (7-9 mm). This ranking correlates with the structural geometry and layer orientation. The bottom face, being the stack end, allows more compressive deformation without critical damage, whereas the side face, with thinner cross-section, fails earlier. This has direct implications for battery pack design: protecting the side faces of a lithium-ion battery is crucial.

4.4 Quantitative Analysis of Force-Displacement Behavior

To further analyze, I compute the energy absorption until the safety limit for each configuration. Using trapezoidal numerical integration of the force-displacement curves, I derive the energy \(E_a\). Table 2 summarizes these values for representative conditions.

| Crushing Face | Indenter Diameter (mm) | SOC | Safety Limit \(\delta_c\) (mm) | \(E_a\) (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Large Face | 25 | 100% | 10 | 185 ± 15 |

| Large Face | 50 | 100% | 13 | 320 ± 20 |

| Side Face | 25 | 100% | 7 | 95 ± 10 |

| Side Face | 50 | 100% | 8.5 | 150 ± 12 |

| Bottom Face | 25 | 100% | 19 | 480 ± 25 |

| Bottom Face | 50 | 100% | 20 | 520 ± 30 |

The energy absorption is higher for larger indenter diameters, confirming that distributed loading enhances the lithium-ion battery’s ability to withstand deformation. The bottom face absorbs the most energy, aligning with its higher displacement threshold. I propose a simple empirical relation for the safety limit \(\delta_c\) as a function of indenter diameter \(D\) and face constant \(k_f\):

$$ \delta_c \approx k_f \cdot D^{\alpha} $$

where \(\alpha\) is an exponent derived from data fitting. For the large face, \(k_f \approx 0.4\) and \(\alpha \approx 0.3\) when \(D\) is in mm. This rough model underscores the positive correlation between indenter size and safety limit for a lithium-ion battery.

5. Discussion

My experimental findings reveal several key insights about the safety of lithium-ion batteries under mechanical crushing. First, the indenter diameter significantly affects the safety limit. A larger indenter (50 mm) distributes force over a broader area, reducing stress concentration and allowing greater deformation before failure. This is consistent with contact mechanics principles: mean pressure decreases as contact area increases, delaying casing yield. Therefore, in real-world impacts, blunt objects pose less immediate threat to a lithium-ion battery’s mechanical integrity than sharp ones.

Second, SOC does not alter the mechanical failure threshold but influences the post-failure behavior. A fully charged lithium-ion battery contains more electrochemical energy, so if an internal short occurs, the heat release is greater, leading to more violent thermal runaway. This dichotomy is critical for safety management: while the initial damage point is SOC-independent, the consequences are not. Thus, battery management systems should prioritize preventing short circuits in high-SOC conditions.

The force-voltage-temperature profiles provide a diagnostic tool for failure detection. A simultaneous voltage drop and temperature rise is a definitive signature of internal shorting in a lithium-ion battery. In contrast, force fluctuations or drops alone may indicate structural buckling without immediate danger. This tri-modal monitoring can be integrated into battery pack sensors for early warning.

My results also highlight the anisotropic nature of the lithium-ion battery. The safety limits vary by face due to internal construction. The bottom face, corresponding to the stacked layers’ ends, is most robust, while the side face is most vulnerable. This anisotropy must be accounted for in battery pack layout and protection structures. For instance, placing thicker armor on the side faces of a lithium-ion battery module could enhance overall safety.

Furthermore, the failure modes observed align with separator integrity. When the separator is compromised, internal short circuit initiates, leading to thermal runaway. The separator in a lithium-ion battery is a critical safety component; its mechanical properties under compression warrant further study. Improving separator toughness could raise the safety limit of the lithium-ion battery.

Comparing with literature, my findings agree that mechanical abuse of lithium-ion batteries can lead to cascading failures. However, my systematic variation of indenter diameter and SOC provides novel quantitative thresholds for prismatic cells. These data fill a gap in standard safety testing, which often uses fixed indenters.

6. Implications for Battery Pack Design and Simulation

The safety limits derived here offer practical guidelines for designing lithium-ion battery packs. For crashworthiness simulations, engineers can use the critical displacements as failure criteria. For example, if a simulation predicts indentation exceeding 10 mm on a large face with a 25 mm object, the lithium-ion battery is likely to fail. Similarly, side face intrusions beyond 7 mm indicate danger.

I recommend incorporating these thresholds into finite element models of battery modules. The force-displacement curves can be used to define material models for the lithium-ion battery cell under crushing. Additionally, the energy absorption values inform the design of energy-absorbing structures around the battery.

Moreover, the SOC-independent mechanical limits simplify simulation calibration, as the same displacement threshold can be applied regardless of charge state. However, thermal runaway models must account for SOC-dependent energy release. A multi-stage simulation approach: first, mechanical deformation until safety limit; second, if limit is exceeded, trigger a thermal runaway model based on SOC.

For regulatory standards, my results suggest that crushing tests should consider indenter geometry. Current standards may use a single indenter size; incorporating multiple sizes could better represent real-world scenarios. The lithium-ion battery industry could benefit from such refinements.

7. Conclusions

In this comprehensive experimental study, I have investigated the safety limits of a prismatic lithium-ion battery under various crushing conditions. Through methodical testing, I established critical indentation displacements for three faces, two indenter diameters, and three SOC levels. The key conclusions are:

- The safety limit of a lithium-ion battery is strongly influenced by indenter diameter. Larger diameters (50 mm) yield higher critical displacements compared to smaller ones (25 mm), indicating a positive correlation between contact area and mechanical resilience.

- The state of charge does not significantly affect the mechanical safety limit; however, it drastically alters the failure mode. High-SOC lithium-ion batteries are more susceptible to thermal runaway and fire after mechanical failure, whereas low-SOC batteries tend to exhibit casing rupture and leakage without severe thermal events.

- The lithium-ion battery exhibits anisotropic safety performance: the bottom face is most robust (safety limit 19-20 mm), followed by the large face (10-13 mm), and the side face is most vulnerable (7-9 mm). This anisotropy stems from internal layer orientation and structural geometry.

- Force-voltage-temperature monitoring is effective for diagnosing failure modes. A simultaneous voltage drop and temperature rise reliably indicate internal shorting in a lithium-ion battery, whereas force anomalies alone may not signify imminent hazard.

- The energy absorption capacity until failure is quantifiable and higher for larger indenters and the bottom face, providing metrics for crash energy management design.

These findings advance the understanding of lithium-ion battery safety under mechanical abuse. They provide empirical data for validating simulation models and inform the design of safer battery packs. Future work could extend to other lithium-ion battery formats, dynamic loading conditions, and coupled thermal-mechanical modeling. Ultimately, enhancing the mechanical integrity of lithium-ion batteries is crucial for the sustainable adoption of electric vehicles.

In summary, this research underscores the importance of considering loading geometry and battery orientation in safety assessments. The lithium-ion battery, as a core component of modern energy storage, must withstand diverse mechanical insults, and my work contributes to defining its limits under controlled crushing scenarios.