The ever-growing global demand for energy has catalyzed significant advancements in green technologies and energy storage devices. Among these, the lithium-ion battery stands as the preferred technology for secondary energy storage in applications ranging from portable electronics to electric vehicles and grid systems, owing to its high power density, long service life, and compact size. The market for lithium-ion batteries is substantial and continues to expand rapidly. However, the energy density of current commercial lithium-ion batteries often falls short of meeting the escalating demands, particularly for extended-range electric vehicles. Therefore, the development of lithium-ion batteries with higher energy densities is paramount.

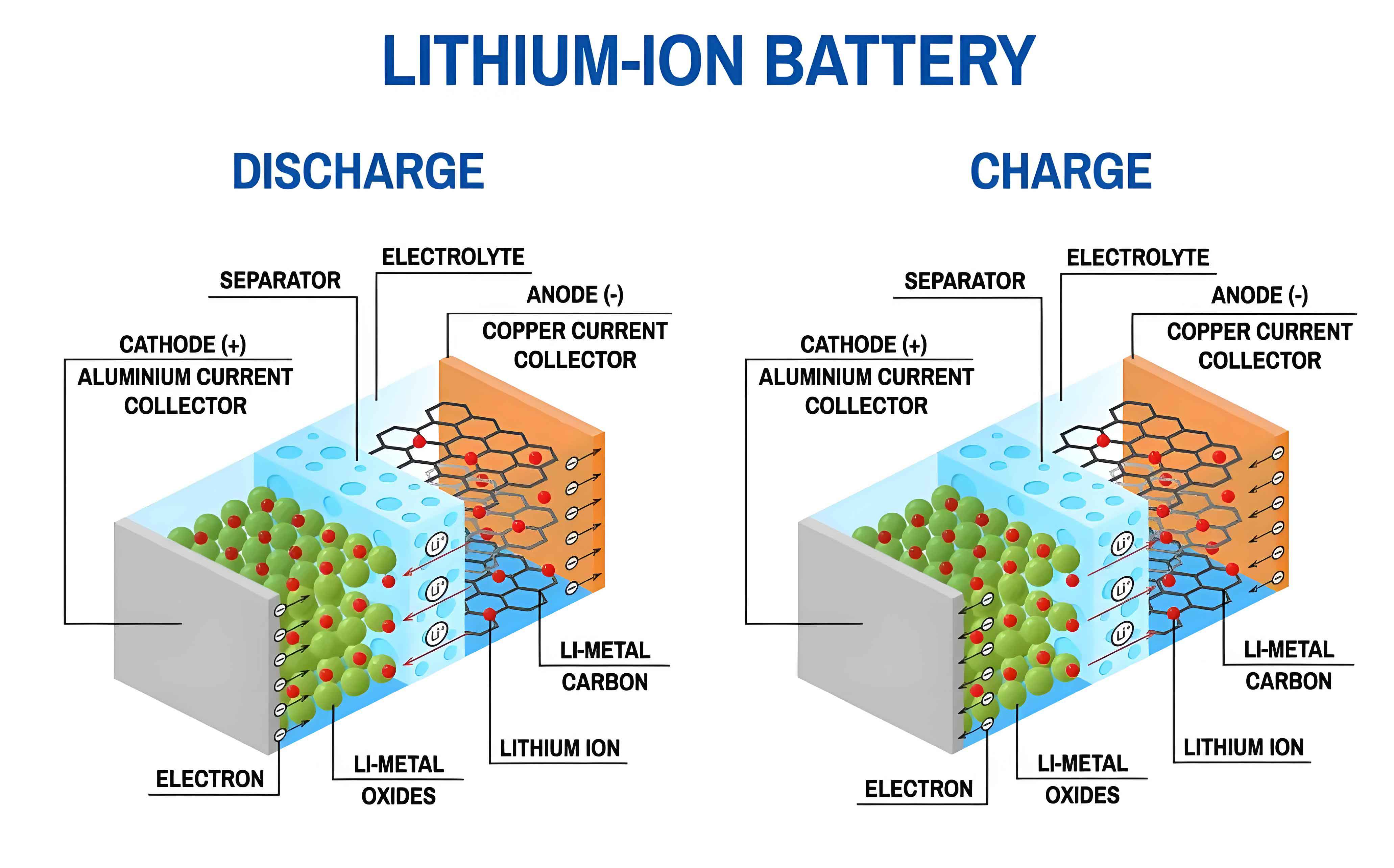

The core components of a lithium-ion battery include the cathode, anode, electrolyte, and separator. The anode active material plays a critical role in energy storage. Silicon has emerged as one of the most promising next-generation anode materials for lithium-ion batteries due to its exceptionally high theoretical specific capacity (approximately 4200 mA h g⁻¹), natural abundance, low cost, and environmental friendliness. Its lithium insertion potential of about 0.4 V versus Li/Li⁺ helps increase the overall output voltage of the cell while effectively suppressing lithium dendrite formation. Despite these compelling advantages, the practical application of silicon anodes in lithium-ion batteries has been severely hampered by several intrinsic challenges.

The primary failure mechanisms of silicon-based anodes in a lithium-ion battery can be categorized into mechanical instability and chemical instability. Mechanical instability arises from the massive volume change (up to 300-400%) during the alloying/dealloying reaction with lithium, described by:

$$Si + xLi^+ + xe^- \leftrightarrow Li_xSi$$

The final lithiated phase at room temperature is Li₁₅Si₄, corresponding to a theoretical capacity of 3579 mA h g⁻¹. This severe, anisotropic expansion and contraction generate immense mechanical stress, leading to particle cracking, pulverization, and loss of electrical contact within the electrode. Chemical instability stems from the continuous fracture and reformation of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) layer on the constantly changing silicon surface. This process irreversibly consumes lithium ions and electrolyte, thickens the electrically insulating layer, increases impedance, and ultimately causes rapid capacity fading in the lithium-ion battery.

Nanostructuring has proven to be a fundamental and effective strategy to mitigate these issues. By reducing the particle size to the nanoscale, the absolute volume change per particle is diminished, and stress can be dissipated more readily, preventing catastrophic fracture. Furthermore, nanostructures offer shortened diffusion pathways for lithium ions, increased surface area for electrolyte contact, and enhanced reaction kinetics. The evolution of silicon nanostructures across different dimensions—from zero-dimensional (0D) particles to three-dimensional (3D) porous frameworks—provides a versatile toolkit for synergistically optimizing volume accommodation, conductivity, and structural integrity in lithium-ion battery anodes.

Zero-Dimensional (0D) Silicon Nanostructures

Zero-dimensional silicon nanomaterials, primarily silicon nanoparticles (SiNPs) and silicon quantum dots (SiQDs), are characterized by their small size (typically 1-100 nm). Their advantages for lithium-ion battery anodes are twofold: first, the small dimensions inherently shorten the lithium-ion diffusion distance and reduce polarization; second, the reduced absolute volume expansion per particle helps alleviate mechanical stress during cycling. However, bare SiNPs tend to suffer from severe aggregation, leading to non-uniform electrochemical reactions and fast capacity decay.

Advanced designs focus on encapsulating SiNPs within protective and conductive matrices. A prominent approach involves constructing porous, heteroatom-doped carbon layers. For instance, nitrogen/sulfur co-doped carbon frameworks uniformly encapsulating silicon have been developed. This design effectively passivates the electrode/electrolyte interface, mitigates volume expansion, and significantly enhances electronic/ionic conductivity. The composite demonstrated a reversible capacity of 1110.8 mA h g⁻¹ after 1000 cycles at 4 A g⁻¹ in a lithium-ion battery.

Another innovative design involves creating core-shell heterostructures, such as Si@V₃O₄@C. Theoretical simulations indicated that the in-situ formed V₃O₄ interlayer facilitates rapid Li⁺ diffusion, while the amorphous carbon shell improves electronic conductivity and structural stability. This material delivered a capacity of 1061.1 mA h g⁻¹ after 700 cycles at 0.5 A g⁻¹. Furthermore, utilizing industrial silicon waste, researchers have fabricated nanocrystalline silicon anodes with defects (stacking faults, nanotwins) that “pin” the grains, imparting high mechanical stability. Electrodes with 80 wt.% of this reinforced silicon retained a capacity of 2180.9 mA h g⁻¹ after 200 cycles, showcasing the potential of advanced 0D material engineering for durable lithium-ion batteries.

The integration of SiNPs with carbon spheres is also a successful strategy. Using a one-pot hydrothermal method, meso-macroporous carbon spheres containing a high loading (40 wt.%) of etched SiNPs were synthesized. This Si/C composite exhibited a high initial capacity of 1300 mA h g⁻¹ and maintained 90% capacity retention after 200 cycles, supporting fast charging within 12 minutes. A more intricate design involves dispersing ultra-small amorphous silicon nanodots (SiNDs, ~0.7 nm) within carbon nanospheres, which are then welded onto the walls of a macroporous carbon framework (MPCF) via vertical graphene (VG). This MPCF@VG@SiNDs/C architecture provides abundant lithium storage sites, fast Li⁺ transport paths, and exceptional stability, achieving 1301.4 mA h g⁻¹ after 1000 cycles at 1 A g⁻¹ with no obvious decay.

The performance of selected 0D silicon-based anodes is summarized below:

| Material | Key Feature | Cycle Performance (mA h g⁻¹) / Cycles / Current | Reference Concept |

|---|---|---|---|

| Si-CBPOD | N/S-doped carbon framework | 1110.8 / 1000 / 4 A g⁻¹ | Stable interface, enhanced conductivity |

| Si@V₃O₄@C | Core-shell heterostructure | 1061.1 / 700 / 0.5 A g⁻¹ | Fast Li⁺ diffusion interlayer |

| MPCF@VG@SiNDs/C | Ultra-small SiNDs in 3D carbon | 1301.4 / 1000 / 1 A g⁻¹ | Dispersion, vertical graphene conduction |

| Si/C Composite Spheres | Mesoporous carbon sphere host | 1170 (90% retention) / 200 / N/A | Stress buffering, fast kinetics |

In summary, 0D silicon anodes benefit from shortened ion paths and reduced stress gradients. Their primary challenge lies in controlling aggregation and ensuring a stable interface, which is effectively addressed through sophisticated carbon composite engineering for high-performance lithium-ion batteries.

One-Dimensional (1D) Silicon Nanostructures

One-dimensional silicon nanostructures, such as silicon nanowires (SiNWs) and silicon nanotubes (SiNTs), offer unique advantages for lithium-ion battery anodes. Their elongated morphology allows for efficient strain relief along the radial direction during volume changes, preventing pulverization. The 1D structure also facilitates direct electron transport along the axis and provides a large surface-to-volume ratio. Common synthesis methods include metal-assisted chemical etching (MACE), chemical vapor deposition (CVD), and template-based approaches.

The template method is widely used for its simplicity. For example, using a silicon-magnesium alloy as a template and polydopamine as a carbon/nitrogen precursor, a 1D tubular Si@N-doped carbon composite was fabricated. The tubular structure and carbon confinement effectively alleviated volume expansion, yielding a stable capacity of 583.6 mA h g⁻¹ after 200 cycles. Another innovative template utilizes cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs). By leveraging their self-assembly properties, silicon nanoquills (SiNQs) with a porous tubular morphology were created. The presence of a native SiOx layer on the SiNQ surface was crucial for stable cycling. When blended with graphite, these water-dispersible SiNQs could significantly boost the capacity of conventional graphite anodes in a lithium-ion battery.

Integrating 1D silicon with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) is a powerful strategy to enhance conductivity. An in-situ pyrolysis strategy was used to encapsulate Si@SiOx particles into boron and nitrogen co-doped carbon nanotubes (BNCNTs), forming Si@SiOx@BNCNT. Finite element analysis confirmed the high mechanical strength of BNCNTs, which, combined with the SiOx layer, provided dual constraints against silicon expansion. This electrode delivered a high reversible capacity of 1700 mA h g⁻¹ at 200 mA g⁻¹ and stable cycling for over 700 cycles. In another design, a flexible and robust array was constructed by weaving ordered SiNWs with a “carbon chain” consisting of short carbon nanofibers (CNFs) and long CNTs. This SiNW/CNF/CNT array electrode, with a high Si loading (6.92 mg cm⁻²), maintained a capacity of 1602 mA h g⁻¹ after 1000 cycles at 2 A g⁻¹ and showed excellent flexibility, with less than 1% capacity decay after 100 bending cycles—a promising feature for flexible lithium-ion batteries.

CVD enables the precise construction of complex 1D architectures. A sandwich-structured CNT/SiNPs/SiC anode was fabricated, where Si nanoparticles are sandwiched between an inner CNT matrix and an outer SiC rigid layer. The SiC layer suppresses stress, while the CNTs buffer stress and conduct electrons. This synergistic structure, along with a stabilized SEI, enabled the anode to retain 85.5% capacity after 1000 cycles at 4 A g⁻¹. The development of 1D structures represents a revolutionary step in anode design for lithium-ion batteries, effectively tackling expansion and conductivity issues, though scalability and cost remain considerations.

Two-Dimensional (2D) Silicon Nanostructures

Two-dimensional silicon nanomaterials, like silicon nanosheets (SiNSs) and silicene, feature ultra-thin layered geometries (thickness < 10 nm). This structure offers high flexibility, a large surface area exposing abundant active sites, and anisotropic lithium-ion diffusion (fast in-plane, limited cross-plane). These characteristics help mitigate mechanical degradation and improve reaction kinetics in lithium-ion battery anodes. Synthesis methods include chemical vapor deposition, magnesiothermic reduction of layered precursors, and chemical/electrochemical exfoliation.

Coating 2D silicon with carbon is essential for enhancing conductivity and stability. A 2D mesoporous silicon nanosheet/carbon (pSi@C) composite was synthesized using a sol-gel and magnesiothermic reduction process with a CTAB-EDTA template. The 2D nanosheet shortens the Li⁺ diffusion distance vertically, while the carbon coating limits volume expansion. This pSi@C composite delivered 2236 mA h g⁻¹ after 150 cycles at 1 A g⁻¹. A simple, scalable magnesiothermic reduction of cheap silicon powder was also employed to produce SiNSs. After carbon coating, the Si-NSs@C material exhibited a high initial capacity of 2770 mA h g⁻¹ at 0.1C and stable cycling.

Electrochemical and chemical exfoliation methods offer alternative routes. A one-step molten salt-induced exfoliation and reduction process converted natural clay into high-quality, porous Si nanosheets (5 nm thick). The carbon-coated Si nanosheet anode demonstrated an impressive 92.3% capacity retention after 1500 cycles at 1 A g⁻¹. Another approach used a selective etching-reduction process to fabricate ultra-thin SiNSs (<2 nm). After hybridization with reduced graphene oxide (rGO), the Si-NSs@rGO composite showed exceptional rate performance (1727.3 mA h g⁻¹ at 10 A g⁻¹) and cycling stability, with a negligible average decay rate of 0.05% per cycle over 1000 cycles at 2 A g⁻¹. The ultra-thin nature of SiNSs is key to their high lithium utilization and reversibility in lithium-ion batteries.

Green synthesis routes are also emerging. For instance, a rapid CO₂ exfoliation of Zintl phase CaSi₂, followed by mild ultrasonication, produced ultrathin Si/SiOx nanosheets. Coated with a thin carbon layer, the Si/SiOx/C nanosheet electrode retained a capacity of 1400 mA h g⁻¹ after 200 cycles at 0.1 A g⁻¹. While 2D silicon structures offer excellent strain accommodation and kinetics, challenges include nanosheet restacking and complex synthesis, particularly for silicene. The performance of selected 2D anodes is compared below:

| Material | Synthesis Method | Key Performance (Capacity / Cycles / Current) | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| pSi@C Nanosheets | Sol-gel & Magnesiothermic | 2236 mA h g⁻¹ / 150 / 1 A g⁻¹ | Short vertical Li⁺ path, mesoporous |

| Si-NSs@C | Magnesiothermic Reduction | ~2400 mA h g⁻¹ (0.1C) / 100 / 0.5C | Scalable, high initial capacity |

| Si Nanosheets@C (from clay) | Molten Salt Exfoliation | 865 mA h g⁻¹ / 1500 / 1 A g⁻¹ | Exceptional long-term cyclability |

| Si-NSs@rGO | Etching-Reduction | 1727.3 mA h g⁻¹ (10 A g⁻¹) / 1000 / 2 A g⁻¹ | Ultra-thin, ultra-high rate |

Three-Dimensional (3D) Silicon Nanostructures

Three-dimensional silicon nanostructures, such as porous silicon and silicon nanosponges, represent a holistic approach to anode design. Their interconnected porous network provides internal void space to accommodate volume expansion, a continuous pathway for electron conduction, and large pores for rapid liquid-phase lithium-ion transport, minimizing polarization in the lithium-ion battery.

Magnesiothermic reduction is a common technique for creating 3D porous silicon. By reducing silica templates, 3D macroporous Si with an interconnected structure was synthesized. After carbon coating, the 3D Si@C electrode exhibited excellent cycling stability, retaining 1058 mA h g⁻¹ after 800 cycles (91% retention). Another design involved embedding Si nanoparticles into a 3D honeycomb-like carbon framework (Si@PVPC) constructed via sol-gel, carbonization, and acid washing. The stable carbon framework offered fast ion diffusion and charge transfer, while its ample channels accommodated Si expansion. The Si@PVPC anode delivered 1294.3 mA h g⁻¹ after 1400 cycles at 2 A g⁻¹, demonstrating outstanding longevity.

Combining freeze-drying with magnesiothermic reduction, a 3D graphene-wrapped porous nano-silicon composite (P-Si@rGO) was prepared. The highly dispersed and individually wrapped Si particles, along with a porous structure and strong Si–O–C interaction, endowed the composite with robust kinetics and buffer space. It maintained 1123 mA h g⁻¹ after 500 cycles at 1 A g⁻¹. Surface functionalization strategies also yield advanced 3D structures. For example, CNTs and SiNPs were encapsulated within carbon derived from a zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-67). The multi-dimensional interconnected CNTs enhanced stability and charge transfer, while the ZIF-derived carbon shell buffered volume change, resulting in stable cycling performance.

A sophisticated 3D design involves creating a freestanding, binder-free electrode paper where Si nanoparticles are uniformly distributed and connected via a 3D network of nitrogen-doped vertical graphene nanosheets (VGs) on porous carbon fibers (PCFs). This VGs@Si@PCFs structure effectively addressed mechanical and chemical stability issues. It exhibited a high reversible capacity of 2205 mA h g⁻¹ at 0.1 A g⁻¹ and remarkable cycling stability, retaining 83.5% capacity after 3000 cycles at 1.0 A g⁻¹. Mechanical modeling confirmed that the porous structure significantly reduces overall strain, minimizing fatigue. The 3D architecture is currently among the most promising for balancing performance and practical manufacturability in lithium-ion batteries.

Other Silicon-Based Material Systems and Structural Modifications

Beyond nanostructured pure silicon, other material systems and structural designs are crucial for the practical deployment of silicon-based anodes in lithium-ion batteries.

Micron-Sized Silicon Structures

Micron-sized silicon (μSi) offers higher tap density, lower surface area (reducing side reactions), and potentially higher volumetric energy density than nanomaterials. However, it suffers more acutely from particle fracture and long ion diffusion paths. The primary solution is compositing μSi with carbon matrices. One approach assembles nano-Si particles into micron-sized agglomerates coated with conductive carbon (mSi-C). This structure provides good conductivity and a stable SEI, delivering 2084 mA h g⁻¹ at 0.4 A g⁻¹ with 96% retention after 50 cycles and a high tap density. Another strategy directly uses μSi particles. A 3D flexible freestanding anode was fabricated by embedding μSi in a high-conductivity skeleton of carboxylated single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNT-COOH) strengthened by a PVA-PAA cross-linked polymer. This electrode achieved an ultra-high conductivity of 12406 S m⁻¹, a tensile strength of 46.95 MPa, and a stable capacity of 2868.5 mA h g⁻¹ at 0.2C.

Silicon Oxide (SiOx) Anodes

Silicon monoxide and its suboxides (SiOx, 0 < x < 2) are attractive anode materials with a high theoretical capacity (up to ~2000 mA h g⁻¹) and better cycling stability than pure Si. During the first lithiation, irreversible lithium silicate (Li4SiO4) and lithium oxide (Li2O) are formed, which act as a buffering matrix to mitigate the volume change of the active silicon. However, this irreversible reaction leads to low initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE). A low-temperature disproportionation strategy using MnO as a promoter was developed to construct Mn2SiO4-Si-SiOx@C (MSS@C). This approach reduced irreversible lithium consumption, achieving a high ICE of 79.51% and 90.4% capacity retention after 350 cycles. Another method used a “molecular assembly and controlled pyrolysis” approach with APTES as the silicon source to prepare N-doped, in-situ carbon-coated SiOx/C/CNTs composites. After prelithiation, the electrode achieved an ICE of 91.6% and a capacity of 622 mA h g⁻¹ after 400 cycles at 1 A g⁻¹, highlighting progress in making SiOx viable for lithium-ion batteries.

Silicon/Carbon (Si/C) Composite Anodes

Silicon/carbon composites represent the most commercially promising path, combining silicon’s high capacity with carbon’s conductivity and mechanical resilience. The performance is highly dependent on the silicon content, its distribution, and the carbon matrix morphology (graphite, CNTs, graphene, amorphous carbon). For instance, a graphite@silicon@carbon (Gr@Si@C) micron-scale spherical composite (30:40:30 mass ratio) was prepared by mechanical fusion. When blended with commercial graphite to achieve a practical Si content of ~16% in the electrode, the full cell achieved a high energy density of 820 Wh L⁻¹. This underscores the importance of designing composites for balanced performance in commercial lithium-ion batteries.

The following table compares the key characteristics of major silicon-based anode systems for lithium-ion batteries:

| Material Type | Theoretical Capacity (mA h g⁻¹) | Volume Expansion (%) | Typical Cycle Life* | Initial CE (%) | Commercial Viability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure Si (Nano) | ~3579-4200 | ~300 | < 100 (bare) | < 80 | Low; requires extensive engineering |

| SiOx | 1500-2000 | 160-200 | ~500 | 65-80 | Medium; used in high-end applications |

| Si/C Composite | 500-1500 (Si-dependent) | 100-150 | > 1000 | 85-90 | High; leading commercial path (e.g., 4680 cells) |

| μSi/C Composite | 1000-2500 | 150-200 | 100-500+ | 80-88 | Medium-High; focus on high-loading electrodes |

* Cycle life is highly dependent on specific design, Si content, and testing conditions.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The journey to realize high-performance silicon anodes for next-generation lithium-ion batteries is centered on sophisticated nanostructure design. By engineering materials across 0D, 1D, 2D, and 3D dimensions, researchers have made significant strides in mitigating the crippling effects of volume expansion and unstable SEI formation. From encapsulated nanoparticles and stress-relieving nanowires to ultra-thin nanosheets and buffering porous networks, each architectural innovation contributes to enhanced mechanical integrity, faster kinetics, and improved cycling stability in the lithium-ion battery.

Looking forward, several key pathways warrant focused exploration to accelerate the commercialization of silicon-based lithium-ion batteries:

- Innovative Synthesis and Scalable Manufacturing: Future efforts must bridge the gap between elegant lab-scale nanostructures and cost-effective, scalable production. Developing simpler, greener, and more controllable synthesis methods (e.g., advanced templating, scalable vapor deposition) that yield consistent and high-quality materials is essential for industrial adoption.

- Fundamental Mechanistic Understanding and Advanced Characterization: A deeper atomic- and molecular-level understanding of degradation mechanisms, SEI evolution, and stress dynamics is crucial. Leveraging in situ/operando characterization techniques (such as in situ TEM, XRD, XPS, and FTIR) coupled with computational modeling will provide invaluable insights to guide the rational design of more robust anode structures for lithium-ion batteries.

- Synergistic Multi-faceted Modification: The ultimate high-performance silicon anode will likely result from the synergistic combination of multiple strategies: optimal nanostructuring (e.g., yolk-shell, porous), intelligent compositing with conductive/elastic matrices (carbon, metals, polymers), strategic elemental doping, and sophisticated surface engineering (artificial SEI, functional coatings). Pre-lithiation techniques must also be advanced to compensate for initial lithium loss.

- Holistic Battery System Integration: The success of a silicon anode depends on its compatibility with other cell components. Future work must concurrently develop compatible electrolytes (e.g., with fluorinated solvents, new salts), advanced binders (elastic, self-healing), stable high-capacity cathodes, and suitable cell engineering to fully exploit the potential of silicon-based lithium-ion batteries.

In conclusion, multi-dimensional nanostructure design stands as a cornerstone in the evolution of silicon anodes. By continuing to innovate at the intersection of materials science, electrochemistry, and engineering, the vision of a high-energy-density, long-lasting, and commercially viable lithium-ion battery powered by silicon is steadily becoming a tangible reality.