The modern era of portable electronics, electric mobility, and grid-scale renewable energy integration has been fundamentally enabled by the lithium-ion battery. Since their commercialization in the early 1990s, lithium-ion batteries have become the dominant rechargeable energy storage technology due to their superior energy density, long cycle life, and relatively low self-discharge rate. Their role in decarbonizing transportation and enabling a resilient power grid is pivotal. However, the performance and safety of a lithium-ion battery are not perpetual. During long-term operation, these batteries undergo complex electrochemical and mechanical degradation processes, leading to capacity fade, power loss, and ultimately, failure. In severe cases, these processes can culminate in thermal runaway, posing significant safety hazards. Therefore, a deep and systematic understanding of the failure mechanisms of lithium-ion batteries, particularly in demanding energy storage applications, is crucial for advancing their design, prolonging their service life, and ensuring safe operation. This article provides a comprehensive, first-person review of the primary failure modes and their underlying mechanisms, followed by a discussion on strategies for performance optimization.

Fundamental Structure and Operation of the Lithium-Ion Battery

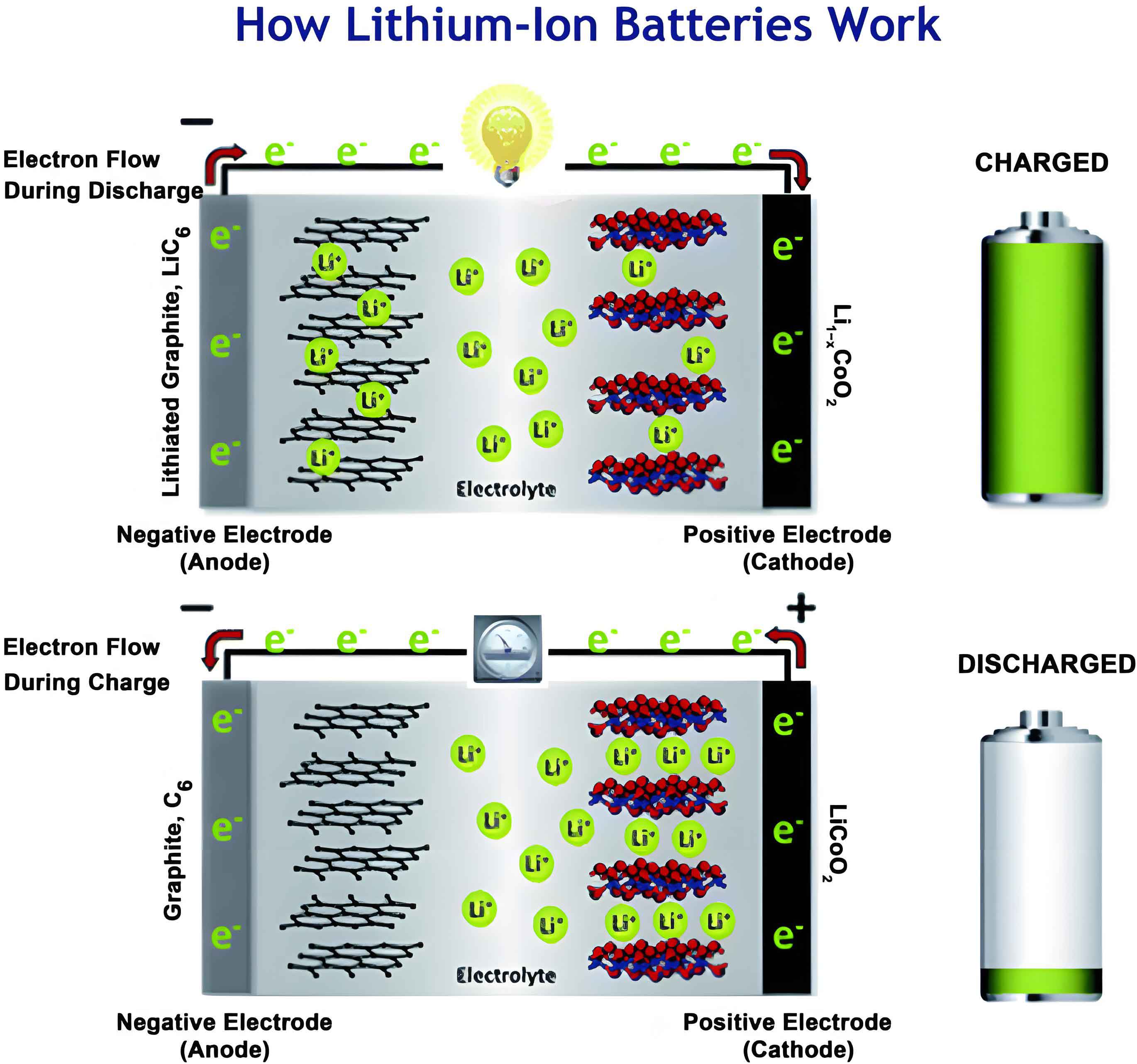

At its core, a lithium-ion battery is an electrochemical cell that stores energy in chemical form and releases it as electrical energy. Its operation hinges on the reversible shuttling of lithium ions between two electrodes. The standard architecture comprises four primary components: the cathode (positive electrode), the anode (negative electrode), the electrolyte, and the separator.

The cathode typically consists of a lithium-containing transition metal oxide (e.g., LiCoO2, LiNixMnyCozO2 – NMC, LiFePO4) coated onto an aluminum current collector. The anode is commonly graphite coated on a copper current collector. During charging, an external power source applies a voltage, driving lithium ions from the cathode lattice, through the ionically conductive but electronically insulating electrolyte, and into the layered structure of the graphite anode. This process is known as intercalation. Simultaneously, electrons flow through the external circuit from the cathode to the anode. The discharge process reverses this: lithium ions de-intercalate from the graphite, travel back through the electrolyte, and re-insert into the cathode material, while electrons flow through the external load, providing useful work. The porous polymer separator physically prevents contact between the anode and cathode while allowing free ionic passage.

The fundamental reactions can be generalized. For a graphite anode:

$$ \text{C}_6 + x\text{Li}^+ + x\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Li}_x\text{C}_6 $$

For a layered oxide cathode (e.g., LiCoO2):

$$ \text{LiCoO}_2 \rightleftharpoons \text{Li}_{1-x}\text{CoO}_2 + x\text{Li}^+ + x\text{e}^- $$

The overall cell reaction is:

$$ \text{LiCoO}_2 + \text{C}_6 \rightleftharpoons \text{Li}_{1-x}\text{CoO}_2 + \text{Li}_x\text{C}_6 $$

The seamless functioning of this “rocking-chair” mechanism is degraded over time by various interrelated failure mechanisms.

Failure Modes and Underlying Mechanisms of the Lithium-Ion Battery

The degradation of a lithium-ion battery is a multifaceted phenomenon, often categorized into structural damage, electrolyte degradation, and thermal runaway. These modes are not isolated but frequently interact, accelerating overall failure.

1. Structural and Mechanical Degradation

Repeated lithium insertion and extraction induces significant mechanical stress within the electrode materials, leading to microstructural evolution and macroscopic damage.

a) Microstructural Evolution and Particle Fracture: Most electrode materials undergo lattice expansion and contraction during cycling. For instance, graphite anisotropically expands by ~10% upon full lithiation. High-capacity materials like silicon can swell by over 300%. This cyclic volumetric change generates internal stress. When the stress exceeds the fracture strength of the active material or the binder holding particles together, micro-cracks form. These cracks propagate with each cycle, fracturing particles. This fracture has several detrimental effects: it creates new, unstable surfaces that consume electrolyte to form fresh Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI), electrically isolates active material fragments, and increases the tortuosity for lithium-ion diffusion. The stress (σ) generated can be related to the strain (ε) and material properties via Hooke’s law for linear elastic materials:

$$ \sigma = E \cdot \varepsilon $$

where \(E\) is Young’s modulus. For a spherical particle undergoing isotropic strain due to lithium concentration change, the strain can be approximated as:

$$ \varepsilon = \frac{\Delta V}{3V} = \beta \cdot \Delta c $$

where \(\beta\) is the partial molar volume of lithium in the host and \(\Delta c\) is the change in lithium concentration.

b) Electrode Delamination and Loss of Electrical Contact: The stress from particle volume change is also transmitted to the interface between the active material coating and the current collector. Repeated cycling can weaken the adhesive bonds, causing the electrode coating to delaminate or peel off. This directly reduces the electrochemically active area and increases the internal resistance. Furthermore, fractured particles may lose electronic contact with the conductive carbon network, rendering them “dead” and inactive. This process is a primary contributor to irreversible capacity loss.

The degradation of mechanical integrity is strongly influenced by operating conditions. Table 1 summarizes the relationship between stress-inducing factors and their consequences.

| Stress-Inducing Factor | Consequence on Lithium-Ion Battery Structure | Primary Degradation Mode |

|---|---|---|

| High Charge/Discharge Rate (C-rate) | Large concentration gradients, inducing severe local stress. | Particle cracking, current collector delamination. |

| Deep Discharge / Overcharge | Extreme lattice expansion/contraction beyond design limits. | Structural phase transitions, particle pulverization. |

| Low Temperature Operation | Increased lithium plating stress, reduced material ductility. | Anode fracture, SEI cracking. |

| Extended Cycle Life | Cumulative fatigue damage from repetitive strain. | Progressive crack propagation, binder degradation. |

2. Electrolyte Degradation and Interphase Evolution

The organic electrolyte, typically a mixture of lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) salt in carbonate solvents, is thermodynamically unstable at the low potentials of the charged anode and the high potentials of the charged cathode. This instability drives continuous side reactions.

a) Formation, Growth, and Reformation of the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI): The most critical and complex degradation process occurs at the anode. During the first charge cycle, the electrolyte reduces at the graphite surface (~0.1 V vs. Li/Li+), forming a protective passivation layer called the SEI. An ideal SEI is ionically conductive for Li+ but electronically insulating, preventing further electrolyte reduction. However, the SEI is dynamic. During cycling, the volume change of the graphite anode cracks the brittle SEI. Fresh, catalytically active graphite surface is exposed, consuming more electrolyte and lithium ions to reform the SEI. This continuous breakdown and reformation leads to a gradual, irreversible consumption of cyclable lithium ions and electrolyte, manifesting as capacity fade. The growth of a thick, resistive SEI layer also increases impedance, reducing power.

The growth of SEI thickness (\(L_{SEI}\)) over time (\(t\)) is often described by parabolic growth kinetics, indicative of diffusion-limited growth:

$$ L_{SEI} = \sqrt{k_p \cdot t} $$

where \(k_p\) is the parabolic rate constant, which depends on temperature and electrolyte composition.

b) Lithium Salt Depletion and Hydrolytic Decomposition: The conductive salt LiPF6 is prone to thermal and hydrolytic decomposition:

$$ \text{LiPF}_6 \rightleftharpoons \text{LiF}_{(s)} + \text{PF}_{5(g)} $$

The Lewis acid PF5 is highly reactive and accelerates solvent decomposition. Furthermore, trace water (even at ppm levels) in the cell triggers a harmful chain reaction:

$$ \text{LiPF}_6 + \text{H}_2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{LiF} + \text{POF}_3 + 2\text{HF} $$

The generated hydrofluoric acid (HF) is particularly damaging. It corrodes transition metals (like Mn, Co, Ni) from the cathode, dissolving them into the electrolyte. These metal ions can then migrate to the anode, get reduced, and catalyze further SEI decomposition and electrolyte reduction in a process known as “cross-talk.” This not only depletes the lithium salt but also poisons the anode surface.

c) Cathode Electrolyte Interphase (CEI) and Transition Metal Dissolution: At the high operating potentials of modern cathodes (>4.3 V), the electrolyte oxidizes, forming a Cathode Electrolyte Interphase (CEI). While less studied than the SEI, CEI growth also consumes lithium and increases impedance. More critically, the structural instability of certain cathode materials (especially layered oxides under high voltage or in presence of HF) leads to dissolution of transition metal ions into the electrolyte. The loss of these ions from the cathode lattice degrades its capacity and structure, while their migration to the anode causes the damaging cross-talk mentioned above. This interplay is a major failure mechanism in lithium-ion batteries using high-nickel NMC or lithium-rich cathodes.

Table 2 provides a summary of key electrolyte degradation pathways and their impact on lithium-ion battery performance.

| Degradation Pathway | Chemical Reaction / Process | Primary Consequence for Lithium-Ion Battery |

|---|---|---|

| Anodic SEI Growth | Reduction of EC, DEC, etc., at anode. Cracking/reformation during cycling. | Irreversible loss of Li+ and electrolyte. Increase in anode impedance. |

| LiPF6 Decomposition | Thermal dissociation: LiPF6 → LiF + PF5 | Loss of conductivity, generation of reactive PF5. |

| Hydrolysis | LiPF6 + H2O → LiF + POF3 + 2HF | Generation of corrosive HF, chain reaction of decomposition. |

| Cathodic Oxidation & CEI | Oxidation of solvent/salt at high voltage cathode surface. | Loss of active Li+, increase in cathode impedance, gas generation. |

| Transition Metal Dissolution | e.g., Mn2+ from LiMn2O4 or Ni from NMC in presence of HF. | Cathode structural decay, anode SEI poisoning via cross-talk. |

3. Thermal Runaway: The Ultimate Safety Failure

Thermal runaway is a catastrophic, self-accelerating failure of the lithium-ion battery where heat generation within the cell outpaces its ability to dissipate heat, leading to a rapid temperature rise, cell rupture, fire, or explosion. It is typically triggered by an initiating event that leads to exothermic reactions.

a) Triggering Mechanisms: Common triggers include:

External Short Circuit: Low-resistance connection between terminals causes massive joule heating.

Internal Short Circuit: Caused by lithium dendrite penetration of the separator, metallic particle contamination, or separator collapse due to crushing or overheating.

Overcharge: Forces excess lithium into the anode (causing plating and dendrites) and over-delithiates the cathode, making it unstable and releasing oxygen.

Overheat: External fire or failure of thermal management system.

b) Stages of Thermal Runaway: The process follows a sequence of exothermic reactions as temperature rises:

Stage 1 (80°C – 120°C): SEI decomposition. The metastable SEI components begin to break down, a mildly exothermic reaction that releases heat and exposes the reactive anode.

$$ \text{SEI} \xrightarrow{\Delta} \text{Gases} + \text{Heat} $$

Stage 2 (120°C – 250°C): Reaction of exposed anode with electrolyte. The lithiated graphite (LixC6) reacts violently with the organic electrolyte in an exothermic reaction.

$$ \text{Li}_x\text{C}_6 + \text{Electrolyte} \rightarrow \text{Gases, Products} + \text{Substantial Heat} $$

Stage 3 (~180°C+): Separator meltdown. The polyolefin separator melts (~130-160°C), causing a massive internal short circuit.

Stage 4 (200°C+): Cathode decomposition and oxygen release. The delithiated, thermally unstable cathode (e.g., LixNiO2) decomposes, releasing oxygen.

$$ \text{Li}_{1-x}\text{NiO}_2 \rightarrow \text{NiO} + \frac{1}{2}\text{O}_2 + \text{Heat} $$

Stage 5 (>250°C): Combustion of electrolyte and other components with the released oxygen, leading to fire and explosion.

The overall heat generation rate (\( \dot{Q}_{gen} \)) follows an Arrhenius relationship and must be compared against the heat dissipation rate (\( \dot{Q}_{diss} \)) governed by Newton’s law of cooling:

$$ \dot{Q}_{gen} = A \cdot \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{RT}\right) $$

$$ \dot{Q}_{diss} = h \cdot A_s \cdot (T – T_{\infty}) $$

where \(A\) is a pre-exponential factor, \(E_a\) is the activation energy, \(R\) is the gas constant, \(T\) is cell temperature, \(h\) is the heat transfer coefficient, \(A_s\) is surface area, and \(T_{\infty}\) is ambient temperature. Thermal runaway occurs when \( \dot{Q}_{gen} > \dot{Q}_{diss} \) and the positive feedback loop is established.

Strategies for Mitigating Failure and Extending Lithium-Ion Battery Life

Addressing the failure mechanisms requires a multi-pronged approach spanning materials innovation, cell engineering, and intelligent operation.

1. Advanced Materials Design

a) Cathode Materials: Developing cobalt-free or low-cobalt, high-stability cathodes (e.g., LiFePO4, high-Mn NMC, disordered rock salts) to reduce cost and improve thermal stability. Surface coating (e.g., with Al2O3, ZrO2) can suppress transition metal dissolution and side reactions with the electrolyte.

b) Anode Materials: Exploring silicon-graphite composites or pre-lithiated silicon anodes with engineered nanostructures (e.g., porous, nanowire) to accommodate volume change. Using lithium metal anotes requires robust solid-state electrolytes or interlayers to suppress dendrites.

c) Electrolytes and Additives: Formulating novel electrolytes: high-concentration “solvent-in-salt” electrolytes, non-flammable fluorinated solvents, or solid-state electrolytes (polymers, sulfides, oxides). Strategic additives (e.g., vinylene carbonate, fluoroethylene carbonate) are crucial for forming a stable, flexible SEI and CEI.

2. Cell Engineering and Design Optimization

Designing electrodes with optimized porosity, graded architectures, and advanced binders (e.g., conductive polymer binders) to better accommodate mechanical strain. Improving separator technology with ceramic coatings for enhanced thermal shutdown and mechanical strength. Implementing robust current collectors and tab designs to minimize localized heating.

3. Intelligent Battery Management and Operational Protocols

The Battery Management System (BMS) is critical for longevity and safety. Key functions include:

Voltage/Temperature Monitoring: Strictly preventing operation outside safe voltage windows (e.g., 2.5V-4.2V for many cells) and temperature ranges (e.g., 15°C-35°C optimal).

Current Limiting: Implementing dynamic charge/discharge rate limits based on cell state and temperature to prevent lithium plating and excessive stress.

State Estimation: Accurately estimating State-of-Charge (SOC) and State-of-Health (SOH) to guide usage and predict end-of-life.

Thermal Management: Active cooling/heating systems to maintain cell temperature homogeneity.

Balancing: Equalizing the charge across cells in a pack to prevent overcharge/over-discharge of individual cells.

Furthermore, operational strategies like partial-state-of-charge cycling (avoiding 100% and 0% SOC) and implementing calendar-life based rest periods can significantly reduce degradation rates.

Conclusion and Future Perspectives

The failure of a lithium-ion battery is a complex, interconnected cascade of electrochemical and mechanical processes. Structural damage from cyclic strain, continuous electrolyte and active lithium consumption via interphase reactions, and the ever-present risk of thermal runaway represent the primary challenges. These mechanisms are influenced by every aspect of the cell: the intrinsic properties of the active materials, the formulation of the electrolyte, the architectural design of the electrodes, and the conditions under which the battery is operated and managed.

Future advancements hinge on developing a more holistic understanding through multi-scale modeling (from quantum chemistry to pack-level thermal models) coupled with advanced in-situ and operando characterization techniques. The integration of artificial intelligence for real-time failure prediction and adaptive management is a promising frontier. The ultimate goal is to design a lithium-ion battery that is not only higher in energy density but is also inherently safe, long-lasting, and sustainably sourced—a key enabler for a fully electrified and renewable energy future. Continued research and development focused on these failure mechanisms will be indispensable in realizing the full potential of lithium-ion battery technology for global energy storage needs.