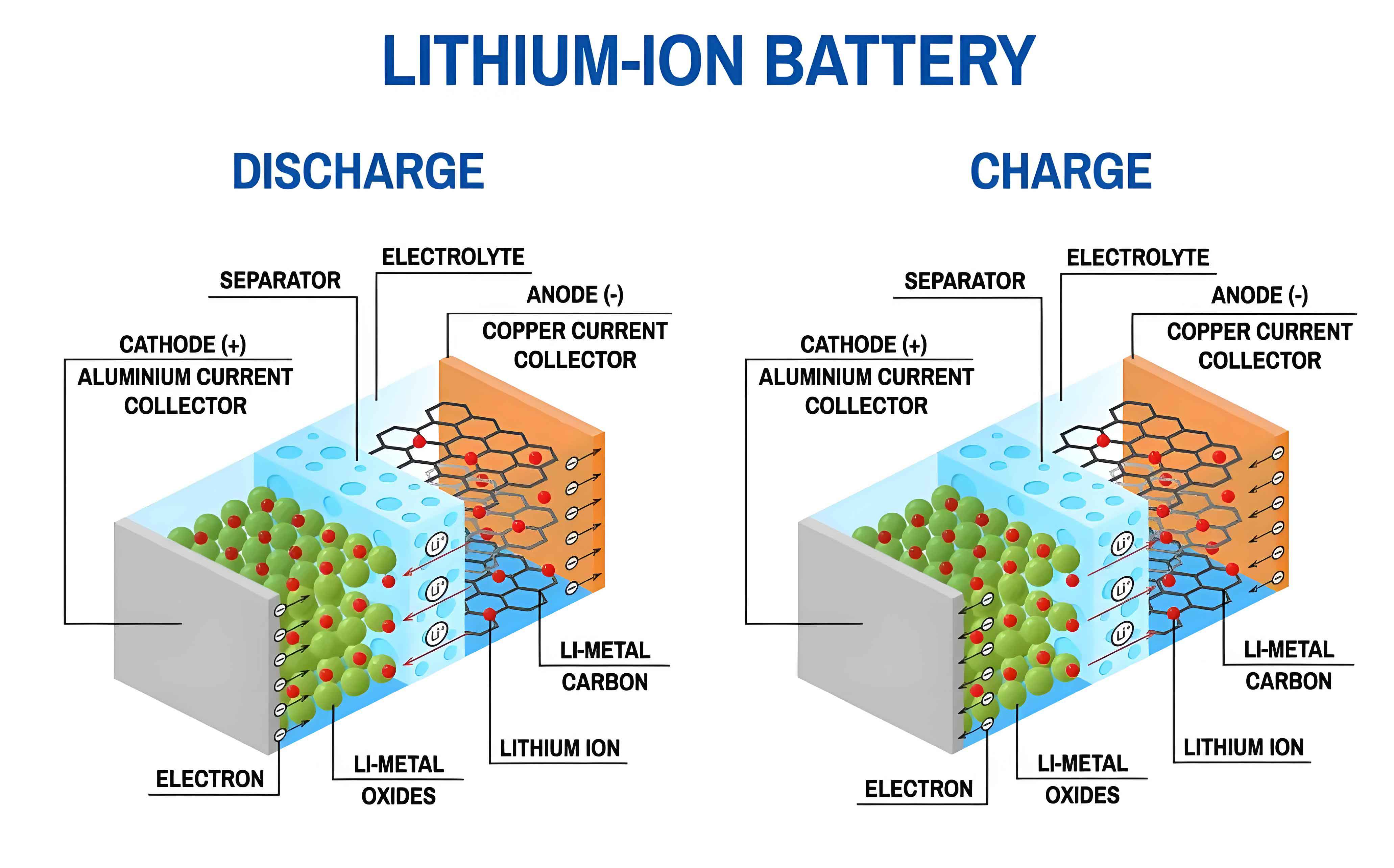

The rapid integration of renewable energy sources into the global power grid necessitates advanced, large-scale energy storage solutions. Among these, electrochemical energy storage, particularly utilizing lithium-ion batteries, has emerged as a cornerstone technology for modern power systems due to its high energy density, long cycle life, and superior power characteristics. Energy storage systems are pivotal for mitigating the intermittency and stochastic nature of renewables like solar and wind, ensuring grid stability, and facilitating the transition towards carbon neutrality. The role of the lithium-ion battery in this paradigm is indispensable, forming the fundamental building block of grid-scale battery energy storage systems (BESS).

However, the widespread deployment of high-capacity lithium-ion battery packs introduces significant safety challenges. Under extreme electrical, thermal, or mechanical abuse conditions, a single cell can undergo thermal runaway—a catastrophic, self-sustaining exothermic reaction. This process can propagate to neighboring cells, potentially leading to large-scale fires or explosions within an energy storage facility. The consequences of such failures extend beyond economic loss, posing severe risks to personnel safety, grid infrastructure, and public confidence in the technology. Therefore, developing robust, early, and reliable safety warning systems is a critical research frontier for the sustainable growth of the energy storage industry.

Traditional safety monitoring for lithium-ion battery systems primarily relies on parameters such as terminal voltage, cell temperature, internal resistance, and gas composition. Each has its merits and limitations. Voltage monitoring is direct but often provides a late-stage warning during thermal abuse. Temperature sensing is common but suffers from a time lag due to the thermal inertia of the cell and the location of sensors relative to the internal heat source. Internal resistance can be indicative of internal short circuits or material degradation but is challenging to measure in real-time within an operational pack. Gas detection, while highly specific to certain failure modes, requires specialized sampling systems and can be complicated by pack ventilation. Consequently, there is a compelling need to explore supplementary or novel parameters that can provide earlier, more definitive warnings of impending cell failure.

This article investigates the potential of surface deformation monitoring as a novel prognostic parameter for lithium-ion battery safety. The underlying hypothesis is that the complex chain of internal reactions during the onset of thermal runaway invariably leads to gas generation. This gas production increases the internal pressure of a sealed cell long before the cell’s temperature rises precipitously, causing measurable mechanical deformation of the cell casing. By detecting this deformation early, it may be possible to trigger safety interventions well ahead of the point of no return. We constructed a multi-parameter testing platform to analyze the surface deformation characteristics of a commercial prismatic Lithium Iron Phosphate (LFP) lithium-ion battery under overcharge abuse conditions, correlating deformation signals with concurrent voltage and temperature data. The factors influencing the deformation profile, including sensor location and mechanical constraints, are analyzed in detail.

Theoretical Background: From Overcharge to Deformation

To understand the genesis of surface deformation, one must first comprehend the sequence of events during the overcharge of a lithium-ion battery. Overcharge pushes the cell beyond its designed upper voltage limit, forcing excessive lithium extraction from the cathode and plating on the anode.

The staged internal reactions can be summarized as follows, leading to gas generation:

- Lithium Plating and Initial Reactions: As the anode potential drops below 0 V vs. Li/Li+, metallic lithium plates onto the anode surface, forming lithium dendrites. These dendrites can react with the electrolyte at relatively low temperatures, producing gases like hydrogen (H₂).

$$ \text{2Li} + 2\text{EC/DMC} \rightarrow \text{H}_2 \uparrow + \text{other organics} $$ - Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) Decomposition and Reformation: The plated lithium and elevated potential can destabilize the existing SEI layer. Its decomposition and subsequent reformation consume electrolyte and generate gases such as carbon dioxide (CO₂), carbon monoxide (CO), and light hydrocarbons (C₂H₄, C₂H₆).

$$ (\text{ROCO}_2\text{Li})_2 \rightarrow \text{Li}_2\text{CO}_3 + \text{C}_2\text{H}_4 \uparrow + \text{CO}_2 \uparrow + \text{etc.} $$ - Electrolyte Decomposition: At higher voltages and temperatures, the organic carbonate-based electrolyte solvents and salt (e.g., LiPF₆) undergo severe decomposition.

$$ \text{LiPF}_6 \rightarrow \text{LiF} + \text{PF}_5 $$

$$ \text{PF}_5 + \text{H}_2\text{O} \rightarrow \text{POF}_3 + 2\text{HF} $$

$$ \text{EC/DMC} \xrightarrow{\text{Heat, Voltage}} \text{CO} \uparrow + \text{CO}_2 \uparrow + \text{Hydrocarbons} $$ - Catastrophic Reactions: Eventually, separator meltdown causes a large internal short circuit, leading to rapid joule heating. This can trigger cathode material decomposition (releasing O₂) and the violent reaction of anode materials, culminating in thermal runaway and, if the safety vent opens, ejection of gases and materials.

The cumulative gas production from these reactions increases the internal pressure (P) of the cell. For a sealed or partially sealed prismatic cell, this pressure exerts a force on the cell casing, primarily the large-area faces which have less structural support compared to the edges. The resulting strain (ε) or deformation is a function of the pressure increase, the material properties of the casing (Young’s modulus E, Poisson’s ratio ν), and the geometry. A simplified relation for the bulge of a thin plate under uniform pressure can be used to conceptualize this:

$$ \Delta P \propto \frac{E \cdot t^3 \cdot \delta}{a^4} $$

Where ΔP is the pressure difference, E is Young’s modulus, t is casing thickness, δ is the center deflection (deformation), and a is a characteristic plate dimension. This indicates that measurable deformation (δ) occurs as internal pressure (ΔP) rises.

The key advantage is that gas generation and the consequent pressure build-up commence during the early, less severe stages of abuse (stages 1 & 2 above), which often occur at lower temperatures. In contrast, significant temperature rise is typically a consequence of the later, more exothermic reactions (stages 3 & 4). Therefore, deformation monitoring has the potential to detect the onset of failure earlier than temperature-based methods.

Experimental Methodology

1. Test Sample: The experiment utilized a commercially available prismatic LFP lithium-ion battery cell, representative of those used in stationary energy storage. Key specifications are provided in Table 1.

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Nominal Capacity | 314 | Ah |

| Nominal Voltage | 3.2 | V |

| Charge Cut-off Voltage | 3.65 | V |

| Discharge Cut-off Voltage | 2.5 | V |

| Dimensions (L x W x H) | 174.26 x 71.65 x 207.01 | mm |

For clarity in discussion, the cell’s two widest faces are termed the “large faces,” and the narrower sides are termed the “side faces.”

2. Instrumentation and Setup: A multi-sensor monitoring platform was established. Strain gauges (BE120-3AA) were affixed at six critical locations to measure surface deformation (strain): the upper, middle, and lower sections of one large face and one adjacent side face. Type-K thermocouples were co-located with strain gauges to measure surface temperature. The cell was initialized to 100% State of Charge (SOC) following standard procedures. To simulate the constrained condition within a typical battery module, the cell was firmly secured in a custom metal fixture with a controlled clamping force applied at the corners (3 N·m torque).

3. Test Protocol: The fully charged cell was subjected to a constant-current overcharge test at 50 A (approximately 0.16C) using a battery cycler. The test continued until the cell entered definitive thermal runaway, defined as a temperature rise rate exceeding 3 °C/s. Voltage, temperature from all points, and deformation (microstrain, με) from all strain gauges were recorded synchronously at a high sampling rate using a data acquisition system.

Results and Discussion: Deformation Characteristics and Early Warning Capability

The overcharge test successfully induced thermal runaway. The synchronized data reveals the temporal evolution of voltage, temperature, and deformation, providing insights into the failure progression.

1. Spatial Analysis of Deformation: The deformation profiles from all six monitoring locations are pivotal for understanding how a lithium-ion battery casing responds to internal pressure. Figure X (conceptual plot) shows the strain versus time for all points. Two critical observations emerge:

- Large Face vs. Side Face Initiation: The strain gauges on the large face consistently registered the initial detectable change in deformation rate earlier than those on the side face. This is mechanically intuitive: the large face, akin to a thin plate, has a lower bending stiffness and is more susceptible to bulging under uniform internal pressure compared to the more rigid, structurally reinforced side faces and edges.

- Upper Section Sensitivity: On both the large face and the side face, the strain gauge positioned on the upper section of the cell detected deformation changes first and exhibited the greatest magnitude of total deformation. This can be attributed to two factors. First, gas bubbles generated during the initial reactions tend to accumulate in the upper volume of the cell due to buoyancy, creating a locally higher pressure zone near the top. Second, the upper section of the casing, particularly near the weld seam of the fill port and vent, may have slightly different mechanical properties or constraints than the solid lower section, making it more prone to initial yielding or flexing.

2. Effect of Mechanical Constraint (Fixture): The experimental use of a fixture significantly influenced the final deformation pattern. While the large face initiated deformation earlier, the final recorded strain amplitude on the large face was lower than that on the side face. This is a direct consequence of the external constraint. The fixture physically restricted the outward bulge of the large face. As internal pressure continued to rise, this constraint caused stress to be redistributed, potentially leading to increased strain on the less-restrained areas of the side faces or causing a more pronounced deformation at the edges. This finding is crucial for real-world applications, as cell deformation within a tightly packed module will be heavily influenced by neighboring cells and module housings.

3. Early Warning Potential: Deformation vs. Temperature: The most significant finding pertains to the early warning capability. Figure Y presents a detailed timeline focusing on the signals from the most sensitive location: the upper section of the large face.

The voltage curve shows the characteristic signature of LFP overcharge: a steep rise as lithium is plated, followed by a plateau and eventual drop due to severe electrolyte decomposition and internal shorts. The temperature curve shows a gradual increase followed by a sharp thermal runaway spike coinciding with vent opening and flaming.

The deformation (strain) curve, however, tells a different story. A distinct and sustained increase in the strain rate is observed approximately 100 seconds before a similarly distinct change in the temperature rise rate is detected. This critical interval is highlighted in the detailed view (Figure Y, inset).

This 100-second lead time can be explained thermodynamically and kinetically. The early-stage gas-producing reactions (lithium-electrolyte reactions, SEI evolution) have lower activation energies and can proceed at moderate temperatures, generating pressure immediately. This pressure acts nearly instantaneously on the cell casing, causing deformation. In contrast, the significant temperature rise is driven by the cumulative heat from these reactions plus the more exothermic later-stage reactions (major electrolyte decomposition, internal shorting). Heat transfer through the cell’s internals (active materials, separators, electrolyte) to the surface sensor involves a significant time delay governed by the cell’s thermal mass and conductivity. This delay manifests as the lag between the deformation signal and the temperature signal.

The quantitative relationship between early gas production and the resultant strain can be modeled. The internal gas generation rate $\dot{n}_{gas}$ is linked to the reaction kinetics. The ideal gas law gives the pressure rise:

$$ P \cdot V = n_{gas} \cdot R \cdot T $$

Differentiating with respect to time and assuming the volume $V$ changes slowly initially, the pressure change rate is:

$$ \frac{dP}{dt} \approx \frac{RT}{V} \frac{dn_{gas}}{dt} + \frac{n_{gas}R}{V} \frac{dT}{dt} $$

The initial pressure rise ($\frac{dP}{dt}$) is primarily driven by the gas generation term ($\frac{dn_{gas}}{dt}$), not the temperature change term. This pressure directly drives deformation ($\delta$ or ε).

Table 2 summarizes the comparative early warning potential of different parameters during the overcharge abuse of this LFP lithium-ion battery.

| Monitoring Parameter | Time of Clear Anomaly (Relative) | Advantage | Limitation in This Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltage | Earliest (During normal charge limit violation) | Fast, direct electrical measurement | Cannot distinguish between normal end-of-charge and early abuse; BMS typically stops charge at voltage limit. |

| Surface Deformation (Strain) | ~100 s before temperature | Directly sensitive to early internal failure mechanisms (gas); Provides lead time. | Signal requires interpretation; Affected by external mechanical constraints. |

| Surface Temperature | Latest | Well-established, intuitive. | Significant thermal lag; Warning may be too late for effective intervention. |

Implications for Safety Warning Systems in Energy Storage

The integration of surface deformation monitoring into BESS safety protocols offers a promising complementary approach. The lead time of ~100 seconds, as observed in this controlled test, is operationally significant. It provides a crucial window for the Battery Management System (BMS) or a dedicated safety controller to execute preventive measures. Potential responses could include:

- Initiation of Aggressive Cooling: Triggering dedicated cooling circuits to suppress the temperature rise of the affected cell and its neighbors.

- Selective and Rapid Discharge: Isolating the affected module or string and safely dissipating its stored energy through a dedicated dump load.

- Alert and Containment: Raising the alarm level for operators and activating internal fire suppression or containment systems pre-emptively.

- Prevention of Propagation: By identifying a failing cell early, measures can be taken to physically or thermally isolate it, breaking the chain reaction that leads to module- or rack-level thermal runaway.

An effective warning system would employ sensor fusion, combining data from voltage, temperature, and deformation sensors. A simple multi-parameter alarm logic could be:

$$ \text{Warning Level} = f(V_{abnormal}, \frac{d\varepsilon}{dt} > \theta_{\varepsilon}, \frac{dT}{dt} > \theta_{T}) $$

Where $\frac{d\varepsilon}{dt}$ is the strain rate, and $\theta_{\varepsilon}$ and $\theta_{T}$ are empirically determined thresholds for strain rate and temperature rate, respectively. An alarm triggered by a combination of an abnormal strain rate and a rising temperature rate would have high confidence and low false-positive rate.

The economic and safety rationale is clear. Preventing a single thermal runaway event from escalating protects high-value capital assets (the entire BESS), ensures grid reliability, and safeguards human life. The cost of integrating strain gauge networks or other deformation sensors (e.g., fiber Bragg gratings, piezoelectric films) is likely marginal compared to the potential loss from a catastrophic fire.

Challenges and Future Research Directions

While the results are promising, several challenges must be addressed for practical engineering application of deformation monitoring in lithium-ion battery systems:

1. Sensor Integration and Durability: Strain gauges must be reliably attached to cell casings and must survive the harsh environment inside a battery pack, including exposure to coolant, potential electrolyte leakage, vibration, and wide temperature cycles (-20°C to 50°C). Newer sensing techniques like embedded fiber optic sensors or pressure-sensitive films warrant investigation.

2. Signal Interpretation and Standardization: Deformation signals are inherently analog and influenced by numerous factors: cell format (prismatic, cylindrical, pouch), casing material and thickness, state of charge, state of health, ambient temperature, and most importantly, the mechanical constraints imposed by the module design. A baseline “healthy” deformation profile during normal cycling (due to mild swelling/contraction) must be established and distinguished from “abusive” deformation. This requires extensive characterization and likely machine learning algorithms for pattern recognition.

3. Multi-Stressor Abuse Conditions: This study focused on overcharge. Deformation characteristics under other abuse conditions (external heating, internal short circuit, mechanical crush) or during aging-induced failures must be studied. The deformation signature may differ based on the failure initiator.

4. System-Level Implementation: Research must scale from single-cell tests to module- and rack-level tests. The interaction between constrained cells, the effect of busbar connections, and the optimal placement of a limited number of deformation sensors in a large array need to be determined.

Future work will involve constructing a comprehensive database of deformation signatures for various lithium-ion battery chemistries (LFP, NMC, LTO) under different abuse scenarios. Coupling this experimental data with multi-physics modeling—integrating electrochemical, thermal, and mechanical models—will be essential. A coupled model can be represented conceptually by:

$$ \text{Electrochemical Model} \rightarrow \dot{n}_{gas}, \dot{q}_{gen} $$

$$ \text{Gas & Pressure Model: } \frac{dP}{dt} = f(\dot{n}_{gas}, T, V) $$

$$ \text{Mechanical Model: } \nabla \cdot \sigma + F = 0 \text{ (with } \sigma \text{ related to } \epsilon \text{ and } P) $$

$$ \text{Thermal Model: } \rho c_p \frac{\partial T}{\partial t} = \nabla \cdot (k \nabla T) + \dot{q}_{gen} $$

Where $\sigma$ is stress, $F$ is body force, $\rho$ is density, $c_p$ is heat capacity, and $k$ is thermal conductivity. Solving such a coupled system will allow for the prediction of deformation profiles and the optimization of sensor placement and alarm thresholds.

Conclusion

This investigation demonstrates that monitoring the surface deformation of a prismatic LFP lithium-ion battery provides a viable and early indicator of incipient failure under overcharge abuse conditions. The deformation is driven by internal gas pressure generated from electrochemical side reactions, which commence before severe temperature escalation. Key findings include:

- The large face of the cell is more sensitive to initial deformation than the side face.

- The upper section of the cell casing shows the earliest and most pronounced deformation, likely due to gas accumulation and structural factors.

- External mechanical constraints significantly alter the final deformation pattern, a critical consideration for module design.

- Most importantly, a measurable change in deformation rate was detected approximately 100 seconds earlier than a corresponding definitive change in surface temperature rate.

This lead time is a substantial advantage for proactive safety management in energy storage systems. It enables earlier detection, which in turn allows for more time to execute mitigation strategies, potentially preventing a single cell failure from cascading into a catastrophic thermal runaway event. While challenges in sensor implementation, signal interpretation, and system integration remain, surface deformation monitoring stands as a promising complementary parameter to traditional voltage and temperature monitoring. By adding this mechanical dimension to the BMS diagnostic suite, the safety and reliability of grid-scale lithium-ion battery energy storage can be significantly enhanced, supporting the secure and sustainable growth of this critical technology in the global energy infrastructure.