The relentless pursuit of higher energy density, longer cycle life, and faster charging capabilities has positioned the lithium-ion battery at the forefront of modern energy storage technology. Its application spans from powering portable electronics to enabling the widespread adoption of electric vehicles and grid-scale storage solutions. At the heart of this technology’s evolution lies the continuous innovation in electrode materials, particularly the anode. While graphite has served as the workhorse anode for decades, its limited theoretical capacity (approximately 372 mAh/g) has become a bottleneck for next-generation energy demands. This has spurred intensive research into alternative materials with higher lithium storage capabilities.

Among the candidates, silicon has garnered significant attention due to its exceptionally high theoretical capacity (up to 4200 mAh/g). However, its practical application is severely hampered by a colossal volume expansion exceeding 320% during lithiation, which leads to rapid mechanical degradation and capacity fade. Similarly, tin-based anodes, though offering a respectable capacity (~994 mAh/g), suffer from analogous volume change issues and unstable solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation. Within this landscape, germanium (Ge), a group IVA element like carbon, silicon, and tin, has emerged as a highly promising anode material for lithium-ion batteries. Germanium strikes a compelling balance between high capacity, good conductivity, and more manageable volume changes compared to silicon, making it a critical subject of contemporary research.

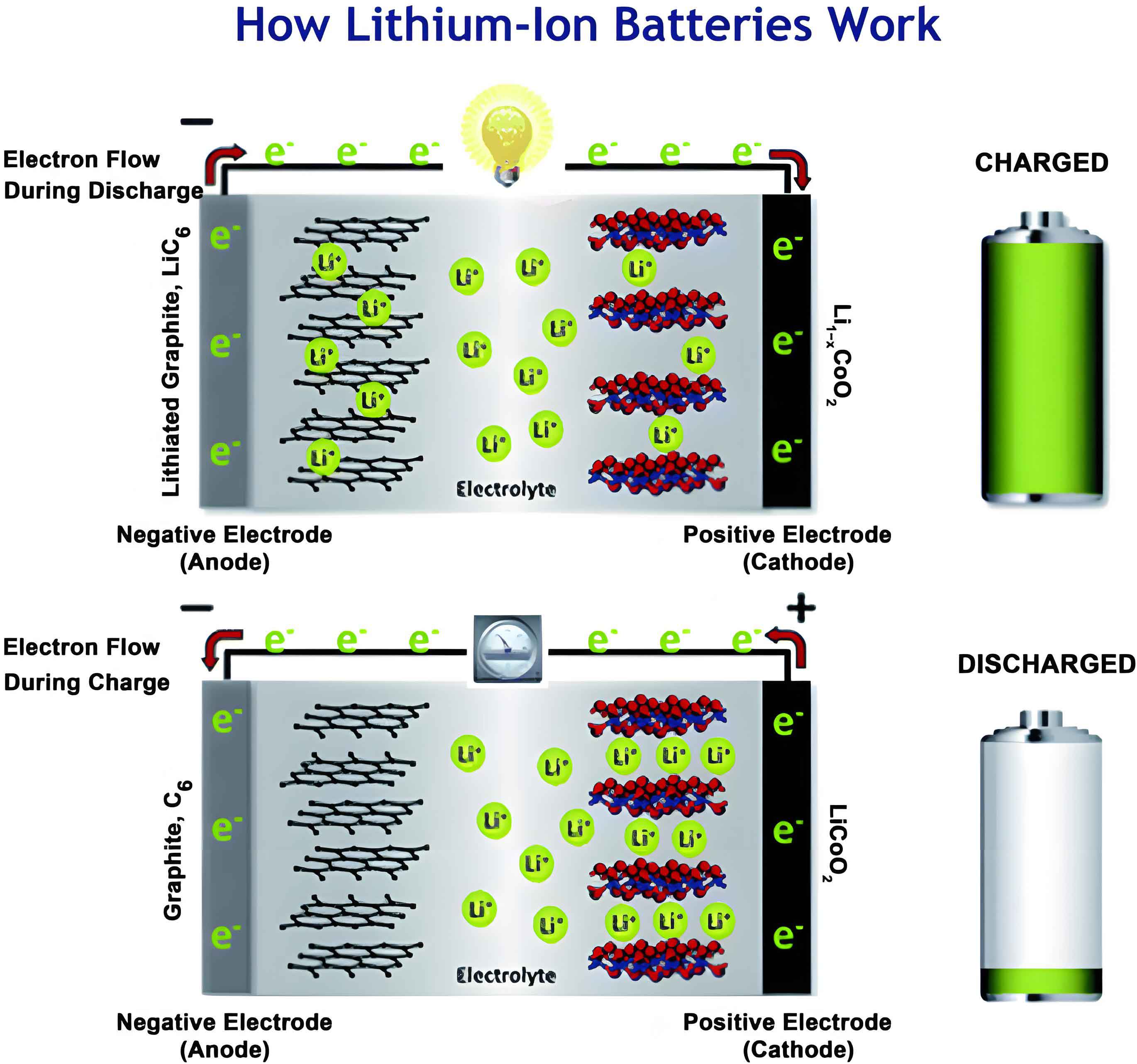

The fundamental operation of a lithium-ion battery is based on the “rocking-chair” mechanism. During charging, lithium ions de-intercalate from the cathode (e.g., LiCoO2), traverse the electrolyte, and intercalate or alloy into the anode material. Concurrently, electrons flow through the external circuit. The discharge process reverses this. The overall cell reaction can be summarized for a typical system:

$$ \text{Cathode: LiCoO}_2 \rightleftharpoons \text{Li}_{1-x}\text{CoO}_2 + x\text{Li}^+ + x\text{e}^- $$

$$ \text{Anode: C}_6 + x\text{Li}^+ + x\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Li}_x\text{C}_6 $$

The performance of this system is intrinsically linked to the anode’s ability to host lithium ions efficiently and reversibly.

Intrinsic Properties of Germanium as an Anode Material

Germanium possesses a unique set of physical and chemical properties that underpin its potential as a high-performance anode in lithium-ion batteries.

Crystal Structure and Lithiation Behavior

Germanium crystallizes in a diamond-cubic structure, similar to silicon but with a larger lattice constant (5.658 Å vs. 5.431 Å for Si). A key advantage of germanium over silicon is its more isotropic lithiation behavior. Studies using in-situ transmission electron microscopy have revealed that silicon nanoparticles often undergo anisotropic strain during lithium insertion, leading to cracking and fracture, especially for larger particles. In contrast, germanium nanoparticles exhibit isotropic swelling during the first lithiation, which distributes stress more uniformly and contributes to better mechanical integrity and electrochemical cycling stability in a lithium-ion battery.

Reaction Mechanism with Lithium

Germanium operates primarily via an alloying mechanism with lithium, offering a high theoretical capacity. The reaction proceeds as:

$$ \text{Ge} + x\text{Li}^+ + x\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Li}_x\text{Ge} $$

The final, fully lithiated phase is generally accepted to be Li22Ge5, which corresponds to a theoretical specific capacity of 1,624 mAh/g. The lithiation pathway involves the formation of several intermediate crystalline phases (e.g., LiGe, Li9Ge4, Li7Ge2, Li15Ge4) that can coexist over a range of potentials, unlike the sharper phase transitions sometimes observed in other alloying anodes.

Superior Lithium-Ion Diffusion and Electronic Conductivity

Two of germanium’s most significant advantages are its high lithium-ion diffusivity and electronic conductivity. Germanium has a relatively narrow band gap (~0.6 eV) compared to silicon (~1.2 eV). This results in an intrinsic electronic conductivity that is about four orders of magnitude higher than that of silicon. Furthermore, the diffusion coefficient of lithium ions in germanium is approximately 400 times greater than in silicon at room temperature. These properties translate directly to excellent rate capability, allowing the lithium-ion battery to be charged and discharged at high currents with less polarization. The high conductivity also facilitates direct growth of active material on current collectors, potentially eliminating the need for conductive additives and binders in electrode fabrication.

Despite these outstanding properties, the practical deployment of germanium anodes in commercial lithium-ion batteries faces two primary challenges:

- Substantial Volume Change: Upon full lithiation to Li22Ge5, germanium undergoes a volume expansion of approximately 230%. While lower than silicon’s >320%, this expansion is still significant enough to induce pulverization of active material, loss of electrical contact, and continuous reformation of the SEI layer.

- High Cost and Resource Scarcity: Germanium is less abundant and more expensive than silicon or graphite, which poses an economic barrier for mass-market applications.

To overcome these hurdles, particularly the volume change issue, researchers have developed sophisticated material design and modification strategies.

Modification Strategies for Germanium-Based Anodes

The overarching goal of modifying germanium-based anodes is to mitigate the detrimental effects of volume expansion while leveraging its high capacity and fast kinetics. The principal strategies can be categorized into four interconnected approaches: Dimensional Nanostructuring, Three-Dimensional Heterostructure Engineering, Carbon Compositing, and Alloying.

Strategy 1: Dimensional Nanostructuring

Reducing the material dimensions to the nanoscale is a fundamental strategy to enhance the performance of electrodes in a lithium-ion battery. Nanostructures provide shorter diffusion paths for lithium ions, larger electrode-electrolyte contact area, and, crucially, a better ability to accommodate mechanical strain. For germanium, various nano-architectures have been explored.

- Nanoparticles (NPs): Synthesizing Ge into nanoparticles significantly reduces the absolute volume change per particle and shortens the Li+ diffusion distance. For instance, Ge NPs synthesized via a magnesium thermal reduction of GeO2 demonstrated a reversible capacity of 909 mAh/g after 250 cycles at a high current density of 3.2 A/g.

- Nanowires (NWs) and Nanotubes (NTs): One-dimensional structures like nanowires grown directly on current collectors offer excellent electronic pathways and ample space to expand radially. Ge nanowire arrays have shown remarkable stability, retaining about 900 mAh/g after 1,100 cycles at high rates. Nanotubes provide both an internal void and a thin wall to accommodate expansion. Porous Ge nanotube arrays have delivered capacities over 1,000 mAh/g at ultra-high rates (40C).

- Nanofilms and Thin Films: Depositing thin films of Ge on conductive substrates creates electrodes with very short diffusion lengths and good adhesion. Performance can be further enhanced by using porous 3D substrates like nickel foam or by coating with elastic polymers like cyclized polyacrylonitrile (c-PAN) to constrain volume expansion. A Ge/c-PAN composite on Ni foam maintained 98% capacity retention after 100 cycles at 1C.

Table 1 summarizes the electrochemical performance of various low-dimensional germanium nanostructures.

| Material Morphology | Capacity After Cycling (mAh/g) | Current Rate / Density | Cycle Number | Capacity Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ge Nanoparticles | 909 | 3.2 A/g | 250 | 98.5% |

| Ge Nanowires (CVD grown) | 894 | 0.2C | 250 | 81.2% |

| Ge Nanofilm on Ni Foam | 676 | 1C | 100 | 98% |

| Ge Nanotube Array | >1,000 | 40C | 400 | 98% |

| Amorphous Ge/TiN Film | 757.85 | 1 A/g | 100 | 58.05% |

Strategy 2: Three-Dimensional Heterostructure Engineering

Building on simple nanostructures, constructing three-dimensional (3D) hierarchical or porous architectures provides additional benefits. These structures offer large surface areas, abundant pores for electrolyte infiltration, and robust frameworks that can buffer volume changes more effectively. The pores act as “expansion reservoirs,” preventing densification and crack propagation within the electrode.

- Porous Micro/Nanostructures: Methods like template-assisted synthesis or thermally induced phase separation can create 3D porous Ge particles. For example, porous Ge particles created via zincothermic reduction exhibited an initial Coulombic efficiency of 88% and over 99.5% capacity retention after 300 cycles at 0.5C.

- Hollow Spheres and Microcubes: Hollow structures provide internal void space to accommodate expansion. Hierarchical Ge microcubes synthesized on Ti foil delivered a high discharge capacity of 1,399 mAh/g at 0.1C. The comparison between solid (A-Ge) and hollow (Z-Ge) microspheres synthesized via a molten salt method clearly showed the advantage of the hollow structure, with Z-Ge maintaining 91.9% capacity after 400 cycles at 0.8C, compared to 76.7% for A-Ge.

- Composite Microspheres with Carbon: Integrating Ge with a carbonaceous matrix in a spherical morphology is highly effective. Spray-dried hierarchical porous Ge/reduced graphene oxide (Ge/rGO) microspheres combine the buffering effect of pores with the conductive, flexible graphene network. This composite retained over 80% capacity after 1,000 long-term cycles at 1C, showcasing exceptional stability for a lithium-ion battery anode.

The performance of various 3D structured Ge-based materials is consolidated in Table 2.

| 3D Material Architecture | Capacity After Cycling (mAh/g) | Current Rate / Density | Cycle Number | Capacity Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D Porous Ge Nanoparticles | 1,415 | 1C | 100 | 95% |

| Hierarchical Ge Microcubes | 1,250 | 0.1C | 200 | 91.8% |

| Porous Ge Particles (Zn reduction) | 1,178 | 0.5C | 100 | 99.9% |

| Ge@Hollow Carbon Spheres | >900 | 0.4C | 100 | >67% |

| Hierarchical Porous Ge/rGO Microspheres | 811 | 1C | 1,000 | >80% |

| Hollow Ge Microspheres (Z-Ge) | 1,217 | 0.8C | 400 | 91.9% |

Strategy 3: Carbon Compositing

Combining germanium with carbon materials is arguably the most prevalent and successful modification strategy for lithium-ion battery anodes. Carbon matrices (graphene, carbon nanotubes, amorphous carbon, etc.) serve multiple critical functions:

- Conductive Network: They enhance the overall electronic conductivity of the electrode.

- Mechanical Buffer: The flexible and resilient carbon can absorb the strain from Ge expansion/contraction, maintaining structural integrity.

- SEI Stabilizer: Carbon can help form a more stable and uniform SEI layer.

- Agglomeration Inhibitor: They physically separate Ge nanoparticles, preventing their aggregation during cycling.

Various composite geometries have been designed:

- Core-Shell Structures: Coating Ge nanoparticles with a uniform carbon shell (Ge@C) is highly effective. The carbon shell constrains the volume change of the Ge core and provides direct electron transfer. Ge@C core-shell nanostructures showed a stable capacity of 985 mAh/g over 50 cycles.

- Embedded Structures: Encapsulating Ge NPs within a porous carbon matrix or graphene sheets ensures good electrical contact and confinement. A composite of Ge NPs embedded in graphite nanosheets via ball-milling (GeGrNPs) delivered 822 mAh/g after 200 cycles at 0.1C.

- Hybrids with Advanced Carbons: Complex hybrids like Ge nanoparticles anchored on vertically aligned graphene networks (Ge@VAGN) or wrapped in reduced graphene oxide (Ge@C/rGO) synergize the properties of different carbon allotropes. A Ge@C/rGO hybrid exhibited an outstanding capacity retention of 96.5% after 600 cycles at a high rate of 2C.

Table 3 presents a selection of high-performing Ge-C composites.

| Composite Material | Capacity After Cycling (mAh/g) | Current Rate / Density | Cycle Number | Capacity Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrodeposited Ge/C Composite | 1,095 | 0.1C | 50 | 89.5% |

| C-Ge Nanowires (Supercritical Synthesis) | >1,200 | 0.2C | 500 | ~89% |

| Ge@Graphite Nanosheet Composite | 822 | 0.1C | 200 | 84% |

| Ge-Graphene Composite Anode | 795 | 0.4 A/g | 400 | 84.9% |

| Ge@C/rGO Hybrid | 1,074.4 | 2C | 600 | 96.5% |

Strategy 4: Alloying

Alloying germanium with other metallic or semi-metallic elements aims to create new phases with improved mechanical, electrical, or electrochemical properties. The secondary element can act as an inactive or active matrix to buffer volume change, enhance conductivity, or even contribute additional capacity.

- Ge-Sn Alloys: Tin is a low-cost, high-capacity element. Alloying Ge with Sn can reduce overall material cost while potentially improving ductility and conductivity. Colloidal SnGe nanorods and Ge1-xSnx alloy nanowires have demonstrated excellent rate performance and stable cycling, with the latter retaining 93.4% capacity after 100 cycles.

- Ge-Si Alloys: Combining the high capacity of Si with the superior kinetics of Ge is an attractive concept. Si1-xGex nanowires and layered structures have been explored, showing capacities exceeding 1,200 mAh/g and improved rate performance compared to pure Si, benefiting from Ge’s faster lithium diffusion.

- Ge-Transition Metal Alloys/Compounds: Alloying with electrochemically inactive but conductive metals like Cu (forming Cu3Ge phases) can create a robust conductive matrix. Ge-Cu composite porous microspheres showed stable cycling over 200 cycles. Furthermore, polyanion-type compounds like Li2FeGeO4 have been investigated as novel anode materials, offering a different lithium storage mechanism based on conversion and alloying reactions.

- Other Alloys: Compounds like GeSe combine alloying (with Ge) and conversion (with Se) reactions, potentially offering high capacity. GeSe nano-comb structures demonstrated 89% capacity retention after 1,000 cycles at 1C.

A summary of key alloyed germanium anodes is provided in Table 4.

| Alloy / Compound Material | Capacity After Cycling (mAh/g) | Current Rate / Density | Cycle Number | Capacity Retention |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu-Ge Core-Shell Nanowire Array | 1,419 | 0.5C | 40 | 80.1% |

| GeSe Nano-Comb | 726 | 1C | 1,000 | 89% |

| Ge(1-x)Snx Alloy Nanowires | ~921 | 0.2C | 100 | 93.4% |

| Fe2GeO4/RGO Nanocomposite | 980 | 0.4 A/g | 175 | >98% |

| Li2FeGeO4 | 669.7 | 0.5 A/g | 200 | 84% |

| Si(1-x)Gex Nanowires | >1,217 | 5C | 100 | 68-75% |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The research on germanium-based anodes for lithium-ion batteries has evolved from studying its fundamental properties to engineering sophisticated nanostructured and composite materials. The synergistic combination of strategies—such as creating carbon-coated, porous Ge nanoparticles or graphene-wrapped Ge-Si alloy nanowires—represents the most promising path forward. These designs successfully address the volume change issue, leading to dramatically improved cyclic stability and rate capability, making a compelling case for their use in high-performance lithium-ion batteries.

However, for widespread commercial adoption in lithium-ion batteries, several challenges must be prioritized:

- Cost Reduction: The high cost of germanium remains a significant barrier. Future work must focus on using minimal amounts of Ge in highly efficient composites, exploring Ge-rich secondary sources, and developing ultra-low-cost synthesis methods (e.g., from waste or via scalable solution processes).

- Material and Electrode Engineering: Further optimization of multifunctional architectures is needed. This includes precise control over porosity, shell thickness in core-shell structures, and the integration with advanced electrolytes and binders to form ultra-stable interfaces.

- Understanding Degradation Mechanisms: Deeper insights into the long-term evolution of the SEI, the mechanical failure modes of complex heterostructures, and the interplay between Ge and its composite matrix during extended cycling are crucial for designing ever-more durable anodes.

- Exploration in New Battery Chemistries: The properties of germanium may prove valuable beyond conventional lithium-ion batteries. Its potential in next-generation systems like solid-state batteries (where volume change is a critical issue) or lithium-sulfur batteries (as a host or catalyst) warrants investigation.

In conclusion, germanium stands as a formidable candidate to push the boundaries of lithium-ion battery technology. Through meticulous nanoscale engineering, clever compositing with carbon, and strategic alloying, the intrinsic limitations of germanium can be effectively mitigated, unlocking its high capacity and ultra-fast kinetics. While economic factors necessitate ongoing innovation, the remarkable progress in Ge-based anode design provides a powerful blueprint for developing next-generation high-energy-density storage systems. The future of the lithium-ion battery may well be shaped by our ability to harness the unique properties of elements like germanium through advanced material science.