In the contemporary landscape of the 21st century, energy storage stands as a paramount research focus. Among various technologies, the lithium-ion battery occupies a pivotal position, distinguished by its high energy density, low self-discharge rate, long cycle life, absence of memory effect, and relatively low environmental impact. Current research on lithium-ion battery technology is intensely concentrated on enhancing cost-effectiveness, energy density, cycle longevity, and, critically, safety. To address these challenges, thermal analysis methods have emerged as indispensable characterization tools, widely applied across the lithium-ion battery industry. These techniques enable profound investigation into the safety, thermal stability, and physicochemical properties of cathode materials, anode materials, electrolytes, separators, and binders. This article delves into the application of thermal analysis in advancing lithium-ion battery technology, providing a detailed examination of its principles and practical uses.

1. The Lithium-Ion Battery: Background and Fundamentals

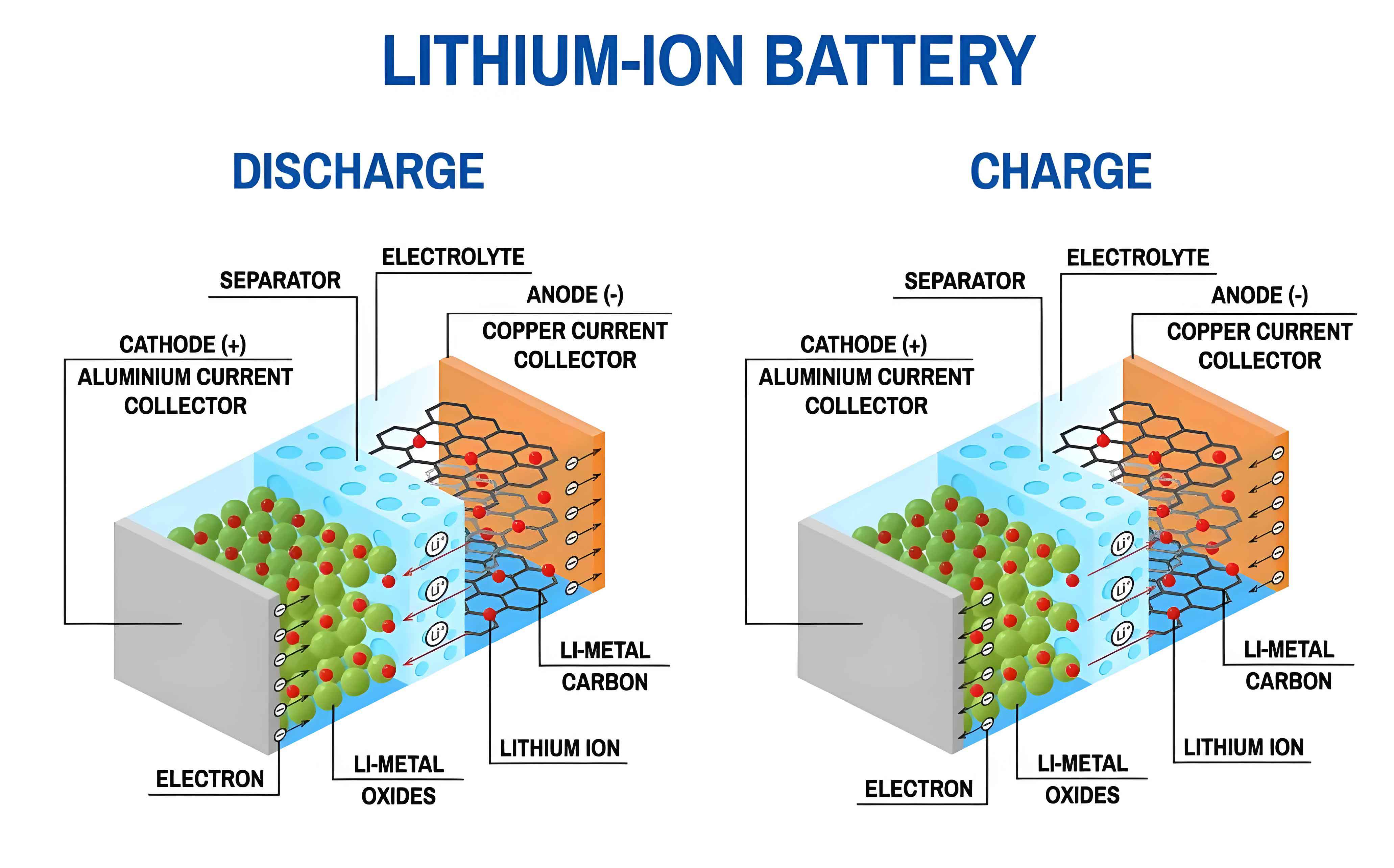

A lithium-ion battery is a rechargeable energy storage device where lithium ions move between the cathode and anode through an electrolyte during charge and discharge cycles. Its development, beginning in the 1980s, has revolutionized portable electronics and is now powering the transition to electric transportation and grid-scale energy storage.

1.1 Key Characteristics of Lithium-Ion Batteries

The widespread adoption of lithium-ion battery systems is driven by a suite of superior properties compared to other rechargeable battery technologies.

| Parameter | Lead-Acid | Ni-Cd | Ni-MH | Lithium-Ion Battery |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Voltage (V) | 2.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 3.6 – 4.2 |

| Specific Energy (Wh/kg) | 30-50 | 40-60 | 60-120 | 150-280+ |

| Energy Density (Wh/L) | 60-100 | 100-150 | 140-300 | 250-730 |

| Cycle Life (to 80% capacity) | 200-500 | 500-1000 | 300-800 | 1000-5000+ |

| Self-Discharge (%/month) | 3-5% | 15-20% | 20-35% | 2-8% |

| Memory Effect | Yes | Yes | Minimal | No |

| Environmental Impact | High (Pb) | High (Cd) | Low | Low-Moderate |

The high voltage of a single lithium-ion battery cell reduces the number of cells needed in series for a given application. Its high specific energy and energy density are crucial for portable electronics and electric vehicles, enabling longer runtime and driving range. The long cycle life translates to better economics and reduced waste, while the low self-discharge rate ensures the battery retains charge when not in use.

1.2 Working Principle and Core Components

The operation of a lithium-ion battery is based on the “rocking-chair” mechanism, where Li+ ions shuttle between the cathode and anode. During charging, Li+ ions are de-intercalated from the cathode material, travel through the electrolyte, and are intercalated into the anode material, while electrons flow through the external circuit to the anode. The discharge process reverses this motion.

For a common graphite | LiCoO2 lithium-ion battery, the electrochemical reactions are:

Cathode (during charge): $$ LiCoO_2 \rightarrow Li_{1-x}CoO_2 + xLi^+ + xe^- $$

Anode (during charge): $$ C_6 + xLi^+ + xe^- \rightarrow Li_xC_6 $$

The core components defining the performance of a lithium-ion battery are:

- Cathode: Typically a lithium metal oxide (e.g., LiCoO2, LiNixMnyCozO2 – NMC, LiFePO4 – LFP) or lithium-rich layered materials.

- Anode: Traditionally graphite (C6), with ongoing research into silicon-based composites, lithium titanate (LTO), and lithium metal.

- Electrolyte: A lithium salt (e.g., LiPF6) dissolved in organic carbonate solvents (EC, DMC, DEC, EMC). Solid-state electrolytes are a major research frontier.

- Separator: A porous polymeric membrane (usually PE or PP) that prevents electrical shorting while allowing ion transport.

- Binders & Conductive Additives: Polymers like PVDF or CMC/SBR hold the active material particles together and onto the current collector.

1.3 Current Research Hotspots and Challenges

Despite their success, lithium-ion battery systems face persistent challenges that drive modern research:

- Energy Density: Pushing beyond 300 Wh/kg for electric aviation and longer-range EVs.

- Fast Charging: Reducing charge times to minutes without compromising safety or cycle life.

- Safety: Mitigating thermal runaway risks stemming from internal short circuits, overcharge, or mechanical abuse.

- Cycle Life & Cost: Extending lifetime for grid storage and reducing $/kWh through material and manufacturing innovations.

- Low-Temperature Performance: Improving power and capacity retention in sub-zero conditions.

Addressing these challenges requires deep material characterization, where thermal analysis plays a critical role.

2. Thermal Analysis Techniques: Principles and Capabilities

Thermal analysis encompasses a group of techniques where the properties of a material are measured as a function of temperature or time under a controlled temperature program. For lithium-ion battery research, three techniques are paramount: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA), and Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA).

2.1 Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

DSC measures the heat flow difference between a sample and an inert reference as both are subjected to a controlled temperature program. It directly quantifies endothermic (heat absorbed) and exothermic (heat released) processes.

Principle: The sample and reference are housed in separate but identical furnaces (or positioned on a single thermoelectric disc). As the temperature changes, any thermal event in the sample (e.g., melting, crystallization, decomposition, solid-state reaction) creates a temperature differential relative to the reference. The instrument supplies or removes heat to maintain both at the same temperature, and this compensated heat flow is recorded.

$$ \Delta H = \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \frac{dH}{dt} dt = K \int_{t_1}^{t_2} \Delta T dt $$

Where \( \frac{dH}{dt} \) is the heat flow rate, \( \Delta T \) is the temperature difference, and \( K \) is a calibration constant.

Applications in Lithium-Ion Battery Research:

- Electrolyte Stability: Determining melting point, boiling point, and onset temperature of exothermic decomposition in sealed crucibles to simulate cell conditions.

- Material Phase Transitions: Identifying melting points of binders, crystallinity changes in separators, and phase transitions in cathode/anode materials.

- Safety Assessment: Measuring the heat released (\( \Delta H \)) from reactions between charged electrode materials and electrolyte, which is a key parameter for evaluating thermal runaway severity.

- Glass Transition (Tg): Characterizing the Tg of polymeric binders and separators, which affects mechanical properties and ion transport at different temperatures.

2.2 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA) and Synchronous TGA-DSC

TGA continuously measures the mass of a sample as it is heated, cooled, or held isothermally in a controlled atmosphere. When coupled with a DSC sensor (TGA/DSC), it simultaneously provides heat flow data.

Principle: The sample is placed on a high-precision balance inside a furnace. The mass change is recorded as a function of temperature or time. Mass losses indicate processes like solvent evaporation, dehydration, decomposition, or combustion. Mass gains can indicate oxidation.

$$ m(T) = m_0 – \sum \Delta m_i(T) $$

Where \( m(T) \) is the mass at temperature T, \( m_0 \) is the initial mass, and \( \Delta m_i \) are the discrete mass losses from various processes.

Applications in Lithium-Ion Battery Research:

- Thermal Stability & Decomposition: Determining the onset temperature and profile of thermal decomposition for cathode and anode materials. This is crucial for understanding at what temperature the active material structure collapses.

- Compositional Analysis: Quantifying the amount of active material, binder, conductive carbon, and residual impurities (e.g., Li2CO3) in an electrode composite. A typical analysis might show steps for binder pyrolysis and carbon black oxidation.

- Binder/Additive Content: Measuring the precise content of polymeric binder in a processed electrode.

- Evolved Gas Analysis (EGA): When TGA is coupled with Mass Spectrometry (MS) or Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR), the gases released during decomposition (e.g., O2 from cathodes, CO2 from electrolytes) can be identified, providing mechanistic insights into failure modes.

| Material | Mass Loss Step | Temperature Range | Probable Process | Information Gained |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiNiMnCoO2 (NMC) | Step 1 | 50-200°C | Loss of adsorbed H2O/solvent | Purity, handling conditions |

| Step 2 | 200-400°C | Decomposition of residual lithium salts (Li2CO3) | Quality of synthesis/surface treatment | |

| Step 3 | >600°C | Major oxygen loss, structural collapse | Intrinsic thermal stability | |

| Graphite Anode with PVDF binder | Step 1 | ~400-500°C (N2) | Pyrolysis of PVDF binder | Binder content (~2-5 wt%) |

| Step 2 | >600°C (Air) | Combustion of carbon (graphite) | Total carbon content |

2.3 Dynamic Mechanical Analysis (DMA)

DMA applies a small oscillating stress (or strain) to a material and measures the resulting strain (or stress) response. It characterizes viscoelastic properties—the balance between elastic (solid-like) and viscous (liquid-like) behavior.

Principle: The sample is subjected to a sinusoidal deformation at a fixed frequency. The stress and strain waveforms are compared. The phase lag (\( \delta \)) between them and their amplitudes are used to calculate:

- Storage Modulus (E’ or G’): The elastic component, representing energy stored and recovered per cycle.

- Loss Modulus (E” or G”): The viscous component, representing energy dissipated as heat per cycle.

- Loss Factor (tan δ): The ratio \( \tan\delta = E”/E’ \), indicating the material’s damping ability.

$$ \sigma(t) = \sigma_0 \sin(\omega t + \delta) $$

$$ \epsilon(t) = \epsilon_0 \sin(\omega t) $$

Where \( \sigma \) is stress, \( \epsilon \) is strain, \( \omega \) is angular frequency.

Applications in Lithium-Ion Battery Research:

- Separator Mechanical Properties: Measuring modulus, tensile strength, and creep/relaxation behavior as a function of temperature. The dramatic drop in storage modulus at the melting point indicates the “shutdown” temperature.

- Viscoelasticity of Binders & Electrodes: Studying how binder properties change with temperature and state-of-charge (due to lithiation/delithiation), which affects electrode integrity and cycle life.

- Solid Polymer Electrolytes: Characterizing the mechanical strength and ion transport (linked to segmental motion near Tg) of solid-state electrolyte films.

3. Comprehensive Applications in Lithium-Ion Battery Component Analysis

3.1 Cathode Materials: Stability Under Thermal Stress

The thermal stability of cathode materials is a primary safety concern, as oxygen release from unstable oxides at high temperatures can trigger violent exothermic reactions with the electrolyte.

Layered Oxides (e.g., LiCoO2, NMC): DSC/TGA studies on charged (delithiated) LiCoO2 show a major exothermic peak around 200-250°C, corresponding to structural decomposition and oxygen release. The onset temperature and total heat released are strongly dependent on the state-of-charge (SOC). NMC materials show a complex decomposition profile where the ratio of Ni:Mn:Co significantly influences stability; higher Ni content generally decreases thermal stability but increases capacity.

Spinel (LiMn2O4): Its degradation often involves Mn dissolution and Jahn-Teller distortion at elevated temperatures, which can be probed by combined thermal and structural analysis.

Polyanion-type (LiFePO4): LFP is renowned for its exceptional thermal and structural stability. DSC/TGA curves show minimal exothermic activity and no significant oxygen release up to very high temperatures (>300°C), making it one of the safest lithium-ion battery cathode chemistries.

| Cathode Material | Major Exothermic Decomp. Onset (DSC, in electrolyte) | Approx. Heat Release (J/g) | Key TGA Observation (in inert gas) | Safety Ranking (Relative) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiCoO2 | ~200-220°C | 450-700 | Major O2 loss ~220-300°C | Lower |

| NMC811 (LiNi0.8Mn0.1Co0.1O2) | ~180-210°C | 500-800 | Multi-step O2 loss starting ~180°C | Lower-Moderate |

| NMC532 | ~220-250°C | 350-600 | O2 loss at higher temperature | Moderate |

| LiMn2O4 | ~250-300°C | 200-400 | Mass loss related to O2 release & Mn reduction | Moderate |

| LiFePO4 | >300°C (very weak) | < 100 | Stable, no significant O2 loss below 400°C | High |

3.2 Anode Materials: From Graphite to Next-Generation

Graphite: The primary concern is the Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI). The initial SEI formation is exothermic. DSC of lithiated graphite (LiC6) with electrolyte reveals that the metastable SEI can decompose and re-form at elevated temperatures (~90-120°C), releasing heat. At higher temperatures (>200°C), the lithiated graphite itself reacts exothermically with the electrolyte.

Silicon-Based Anodes: Silicon offers much higher capacity but suffers from huge volume changes. TGA can monitor the composition of Si-C composites. More critically, the reaction between lithiated silicon (LixSi) and electrolyte is highly exothermic, and DSC is essential for quantifying this risk to guide electrolyte and cell design.

Lithium Titanate (LTO, Li4Ti5O12): Known for its extreme safety and cycle life, LTO has a high lithium insertion potential (1.55 V vs. Li/Li+), which avoids lithium plating and SEI formation. DSC studies show minimal exothermic activity with common electrolytes, making it a very safe choice for demanding applications.

3.3 Electrolyte and Critical Interface Reactions

The thermal behavior of the electrolyte itself and its reactions with electrodes are central to lithium-ion battery safety.

Pure Electrolyte Stability: DSC in high-pressure crucibles can determine the boiling point and the onset of thermal decomposition for LiPF6 salts in carbonate blends (e.g., EC:EMC). A typical LiPF6/carbonate electrolyte begins significant exothermic decomposition around 220-250°C.

Electrode-Electrolyte Reactions (ARC & DSC): The most valuable safety data comes from studying mixtures. For example, DSC of charged NMC cathode mixed with electrolyte shows a sequence of exotherms:

- A minor peak around 100-150°C from SEI breakdown on the cathode surface.

- A major, sharp peak around 200-250°C from the reaction of the highly oxidized cathode surface with the electrolyte, releasing oxygen and heat.

- Subsequent reactions of released gases or hot particles.

The total heat output from these reactions, often exceeding 1000 J/g of cathode material, is what can propel a single cell into thermal runaway.

The self-heating rate (\( dT/dt \)) from these reactions can be modeled using kinetics derived from DSC data, often following an Arrhenius relationship:

$$ \frac{dT}{dt} = \frac{A \Delta H}{C_p} e^{-E_a/(RT)} f(\alpha) $$

Where \( A \) is the pre-exponential factor, \( E_a \) is the activation energy, \( \Delta H \) is the reaction enthalpy, \( C_p \) is heat capacity, and \( f(\alpha) \) is a function of conversion extent \( \alpha \).

3.4 Separators and Binders

Separator Shutdown: A key safety feature of polyolefin separators (PE, PP) is their thermal shutdown. DMA and DSC are used to characterize the melting behavior. As temperature rises, the separator’s pores close (melt) around 130-140°C for PE and ~165°C for PP, increasing resistance and shutting down the cell. DMA precisely shows the associated sharp drop in storage modulus. The “melt integrity” or “breakdown” temperature, where the separator loses all mechanical strength, is also critical and can be determined by DMA or TMA (Thermomechanical Analysis).

Binder Characterization: The glass transition temperature (Tg) of binders like PVDF or SBR, measured by DSC or DMA, influences electrode processing (slurry rheology) and low-temperature performance. A binder below its Tg at operating temperature is brittle and may crack during cycling.

4. Future Perspectives: The Evolving Role of Thermal Analysis

As the lithium-ion battery industry strives for higher performance, lower cost, and absolute safety, the role of thermal analysis will only expand and become more sophisticated.

Advanced and Novel Materials: For next-generation batteries (solid-state, lithium-sulfur, lithium-air), thermal analysis will be fundamental. TGA-DSC will characterize the stability of solid electrolytes (sulfides, oxides, polymers), the melting and crystallization of lithium metal anodes, and the complex multi-step reactions in sulfur cathodes.

In-Operando and Multi-Scale Analysis: The future lies in coupling thermal analysis with other techniques to perform in-situ or in-operando measurements on working battery cells or components. Examples include:

- TGA-MS/FTIR-GC: For real-time identification of volatile decomposition products during cell abuse testing.

- DSC-XRD: Simultaneous thermal and structural analysis to link exothermic events directly to crystallographic phase changes.

- Micro/Nano-Thermal Analysis: Probing local thermal properties (conductivity, diffusivity) of individual electrode particles or interfaces, which is critical for modeling heat generation at the micro-scale.

Predictive Modeling and AI Integration: The vast datasets generated from systematic DSC, TGA, and DMA studies on material families will feed machine learning algorithms. These models can predict the thermal stability and safety of new material compositions before they are ever synthesized, accelerating the design cycle for safer lithium-ion battery chemistries.

Quality Control and Manufacturing: Beyond R&D, rapid thermal analysis techniques will become integrated into quality control workflows for raw material inspection (e.g., checking cathode precursor purity via TGA) and finished electrode characterization (e.g., verifying binder content consistency).

In conclusion, thermal analysis is not merely an auxiliary technique but a cornerstone of modern lithium-ion battery research and development. From fundamental material science to applied safety engineering, DSC, TGA, and DMA provide the critical data needed to understand, improve, and ultimately ensure the reliability of the energy storage systems that power our world. As the technology progresses towards ever more ambitious goals, the insights gleaned from these thermal probes will remain vital in navigating the path to safer, more powerful, and longer-lasting lithium-ion battery systems.