Perovskite solar cells have emerged as a promising photovoltaic technology due to their high absorption coefficients, tunable bandgaps, and excellent charge carrier transport properties. In recent years, the power conversion efficiency of perovskite solar cells has surged from 3.8% to over 26%, approaching the Shockley-Queisser limit for single-junction devices. Wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells, with bandgaps ranging from 1.6 to 1.8 eV, are critical components in perovskite-silicon tandem solar cells, which have the potential to exceed this limit. However, the development of wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells is hindered by issues such as high defect density, severe non-radiative recombination, and phase separation under illumination. These challenges necessitate strategies to improve the crystallinity and reduce defects in perovskite films. Additive engineering has been widely adopted as a simple and effective approach to modulate crystallization kinetics and passivate defects in perovskite layers. In this study, we introduce 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium methanesulfonate (BMM) as a multifunctional additive into the perovskite precursor solution. We systematically investigate the effects of BMM concentration on the morphology, crystal structure, optical properties, and photovoltaic performance of perovskite solar cells. Our findings demonstrate that optimized BMM addition enhances film quality, reduces non-radiative recombination, and improves device stability, leading to high-performance perovskite solar cells.

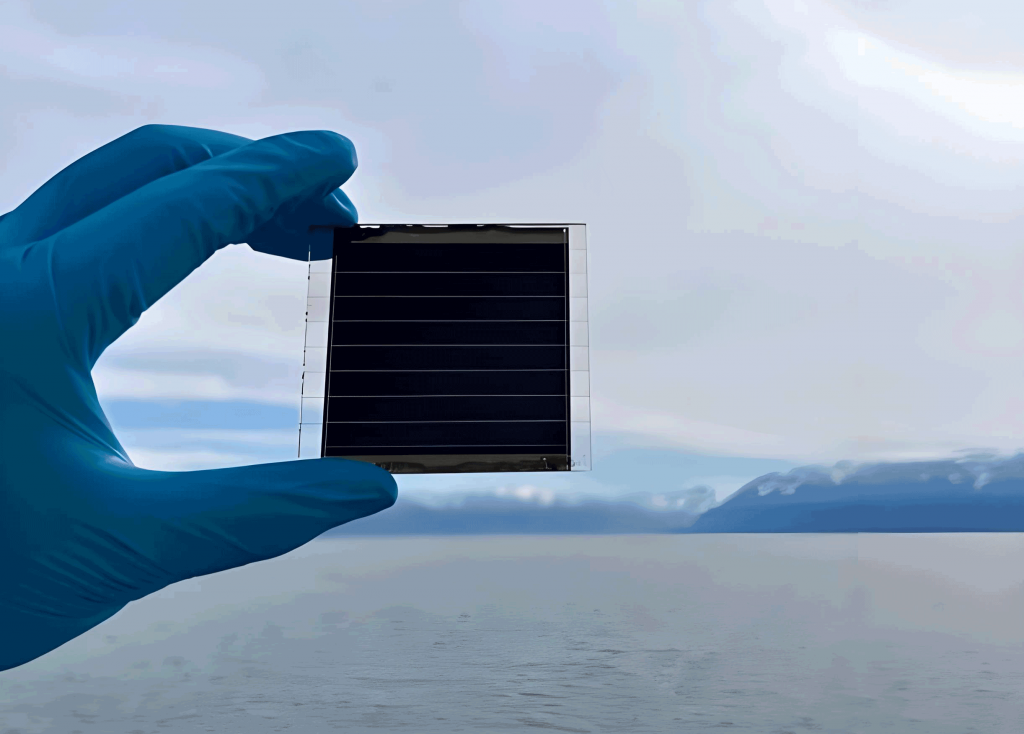

The perovskite solar cells were fabricated with an inverted structure: FTO glass/NiOx/MeO-2PACz/perovskite/PCBM/BCP/Ag. The perovskite composition was FA0.8MA0.15Cs0.05Pb(I0.76Br0.24)3, corresponding to a bandgap of approximately 1.68 eV. The precursor solution was prepared by dissolving FAI, MABr, PbI2, PbBr2, and CsI in a mixture of DMF and DMSO. BMM was added at concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mg/mL to study its impact. The films were deposited via spin-coating with antisolvent engineering using ethyl acetate, followed by annealing. Characterization techniques included scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (UV-Vis), photoluminescence (PL), transient photoluminescence (TRPL), contact angle measurements, and current density-voltage (J-V) profiling. The electronic properties were evaluated using capacitance-voltage (C-V) measurements to determine the built-in potential. Stability tests were conducted under ambient conditions with 10-40% relative humidity.

The morphology of the perovskite films was examined using SEM and AFM. The control film (without BMM) exhibited smaller grains with non-uniform distribution, whereas the film with 1.0 mg/mL BMM showed larger, more uniform grains. This improvement is attributed to the interaction between BMM and PbI2, which slows down crystallization and promotes oriented growth. The AFM results confirmed a reduction in root mean square (RMS) roughness with BMM addition, as summarized in Table 1. The lower roughness enhances interface contact and facilitates uniform deposition of subsequent layers, which is beneficial for charge transport in perovskite solar cells.

| BMM Concentration (mg/mL) | RMS Roughness (nm) | Average Grain Size (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 27.8 | 280 |

| 0.5 | 19.2 | 320 |

| 1.0 | 17.1 | 380 |

| 1.5 | 20.9 | 350 |

XRD analysis revealed that all films displayed characteristic peaks at 14.13°, 19.93°, and 31.86°, corresponding to the (110), (112), and (220) planes of the perovskite structure, respectively. No peak shifts were observed, indicating that BMM did not incorporate into the lattice. However, the peak intensities increased with BMM addition, suggesting improved crystallinity. The enhanced crystallinity reduces grain boundaries and defect states, which is crucial for minimizing non-radiative recombination in perovskite solar cells.

XPS and FTIR studies provided insights into the chemical interactions between BMM and the perovskite. The Pb 4f and I 3d peaks shifted to lower binding energies in BMM-modified films, indicating coordination between the imidazolium nitrogen atoms and uncoordinated Pb²⁺ ions. The FTIR spectra showed a shift in the S=O stretching vibration from 1040 cm⁻¹ to 1036 cm⁻¹, confirming hydrogen bonding between the methanesulfonate group and halide ions. These interactions passivate defects and suppress ion migration, contributing to the stability of perovskite solar cells.

Optical properties were investigated using UV-Vis, PL, and TRPL spectroscopy. The UV-Vis absorption spectra showed enhanced absorption intensity with BMM addition, particularly at 1.0 mg/mL, due to improved film quality. The PL spectra exhibited a blue shift from 749 nm to 745 nm and a significant increase in PL intensity, indicating reduced defect density. The TRPL decay curves were fitted using a bi-exponential model, and the average carrier lifetime (τ_avg) was calculated using the formula:

$$ \tau_{avg} = \frac{A_1 \tau_1^2 + A_2 \tau_2^2}{A_1 \tau_1 + A_2 \tau_2} $$

where A₁ and A₂ are amplitudes, and τ₁ and τ₂ are decay times. The results, summarized in Table 2, show that the carrier lifetime increased from 23 ns for the control film to 67 ns for the 1.0 mg/mL BMM film, demonstrating suppressed non-radiative recombination. This enhancement is critical for improving the open-circuit voltage and overall efficiency of perovskite solar cells.

| BMM Concentration (mg/mL) | PL Peak (nm) | Average Carrier Lifetime (ns) | Absorption Edge (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 749 | 23 | 780 |

| 0.5 | 747 | 47 | 780 |

| 1.0 | 745 | 67 | 780 |

| 1.5 | 746 | 35 | 780 |

Contact angle measurements revealed that BMM addition increased the hydrophobicity of the perovskite films. The water contact angles were 59.4°, 70.1°, 71.1°, and 72.3° for BMM concentrations of 0, 0.5, 1.0, and 1.5 mg/mL, respectively. This improved moisture resistance enhances the long-term stability of perovskite solar cells under ambient conditions.

The photovoltaic performance of the perovskite solar cells was evaluated under AM 1.5G illumination. The J-V curves for devices with different BMM concentrations are shown in Figure 1 (not referenced in text). The key parameters, including open-circuit voltage (V_oc), short-circuit current density (J_sc), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE), are summarized in Table 3. The device with 1.0 mg/mL BMM achieved the best performance, with a V_oc of 1.139 V, J_sc of 21.98 mA/cm², FF of 81.65%, and PCE of 20.27%. In comparison, the control device had a PCE of 17.32%. The improvement is attributed to larger grain size, reduced defects, and enhanced charge extraction. The hysteresis index (HI) was calculated using the formula:

$$ HI = \frac{PCE_{reverse} – PCE_{forward}}{PCE_{reverse}} $$

The HI decreased from 0.077 for the control device to 0.050 for the 1.0 mg/mL BMM device, indicating reduced hysteresis and better charge transport in the perovskite solar cell.

| BMM Concentration (mg/mL) | V_oc (V) | J_sc (mA/cm²) | FF (%) | PCE (%) | Hysteresis Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.091 | 20.33 | 78.17 | 17.32 | 0.077 |

| 0.5 | 1.115 | 21.45 | 79.50 | 19.01 | 0.065 |

| 1.0 | 1.139 | 21.98 | 81.65 | 20.27 | 0.050 |

| 1.5 | 1.122 | 21.20 | 80.10 | 19.05 | 0.058 |

To further understand the electronic properties, we performed C-V measurements and analyzed the Mott-Schottky plots. The built-in potential (V_bi) was derived from the intercept of the linear region of the 1/C² vs. V plot, using the Mott-Schottky equation:

$$ \frac{1}{C^2} = \frac{2}{q \epsilon \epsilon_0 A^2 N_D} (V_{bi} – V) $$

where q is the electron charge, ε is the permittivity of the perovskite, ε₀ is the vacuum permittivity, A is the area, and N_D is the donor density. The V_bi increased from 0.74 V for the control device to 0.95 V for the 1.0 mg/mL BMM device. This higher built-in potential facilitates charge separation and collection, leading to improved J_sc and V_oc in the perovskite solar cell.

Stability tests were conducted by storing unencapsulated devices in air with 10-40% relative humidity. The normalized PCE retention over time is shown in Table 4. After 900 hours, the device with 1.0 mg/mL BMM retained 80.1% of its initial PCE, while the control device retained only 70.3%. The enhanced stability is due to the improved hydrophobicity and reduced defect density, which mitigate moisture ingress and ion migration in the perovskite solar cell.

| Time (hours) | Control PCE Retention (%) | 1.0 mg/mL BMM PCE Retention (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 100 |

| 300 | 85.2 | 92.5 |

| 600 | 76.8 | 86.3 |

| 900 | 70.3 | 80.1 |

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that BMM is an effective additive for improving the performance and stability of wide-bandgap perovskite solar cells. The optimal concentration of 1.0 mg/mL BMM enhances crystallinity, reduces defect density, and suppresses non-radiative recombination. This leads to a significant increase in PCE from 17.32% to 20.27%, along with improved hysteresis and stability. The multifunctional nature of BMM, involving coordination with Pb²⁺ and hydrogen bonding with halides, provides a robust strategy for defect passivation and crystallization control. These findings highlight the potential of ionic liquid additives in advancing perovskite solar cell technology for practical applications, particularly in tandem configurations. Future work will focus on scaling up the fabrication process and integrating BMM-modified perovskite solar cells into large-area modules.