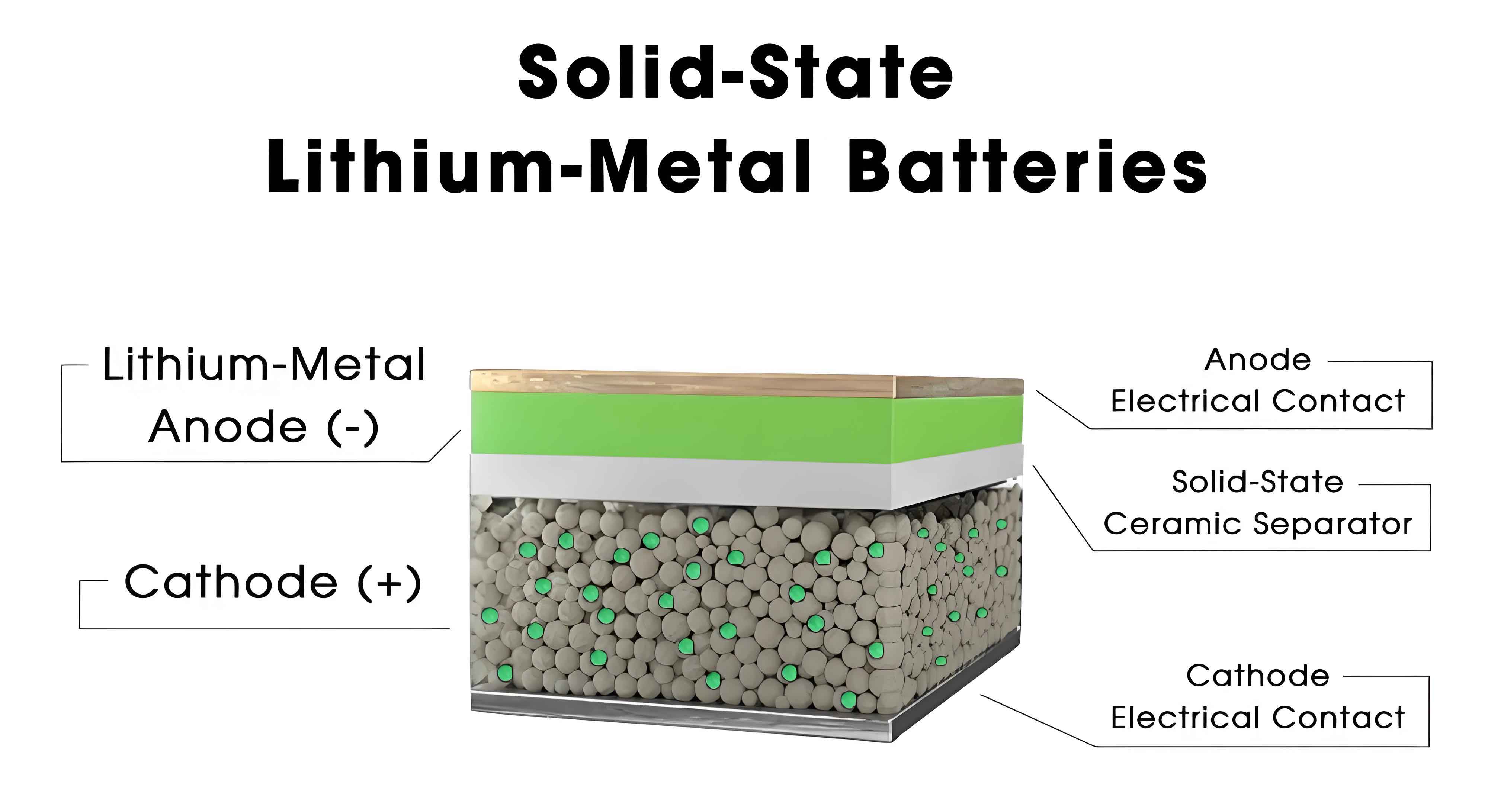

Solid-state lithium metal batteries represent a transformative advancement in energy storage technology, offering unparalleled theoretical energy density and enhanced safety compared to conventional liquid electrolyte systems. However, the performance of solid-state batteries deteriorates significantly at low temperatures (≤0 °C), primarily due to reduced ionic conductivity in solid-state electrolytes and increased interfacial impedance. This review comprehensively examines the latest developments in solid-state electrolyte technologies tailored for low-temperature applications, focusing on material-level strategies to overcome these challenges. We analyze the fundamental ion transport mechanisms, failure modes, and innovative design approaches for inorganic, polymer, and composite solid-state electrolytes. By integrating theoretical models, experimental data, and advanced characterization techniques, this article provides a holistic perspective on enabling reliable operation of solid-state lithium metal batteries under extreme cold conditions.

The evolution of solid-state batteries hinges on understanding ion dynamics in solid-state electrolytes. At low temperatures, ionic conduction is governed by Arrhenius behavior for crystalline materials: $$\sigma = \frac{A}{T} \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{RT}\right)$$ where $\sigma$ is ionic conductivity, $A$ is the pre-exponential factor, $T$ is absolute temperature, $E_a$ is activation energy, and $R$ is the gas constant. For amorphous systems like polymers, the Vogel-Tammann-Fulcher (VTF) model applies: $$\sigma = \sigma_0 T^{-1/2} \exp\left(-\frac{B}{T – T_0}\right)$$ Here, $\sigma_0$ is a constant, $B$ is fitting activation energy, and $T_0$ is the reference temperature. These equations highlight the exponential decline in conductivity with decreasing temperature, underscoring the need for materials with low activation barriers.

Failure mechanisms in low-temperature solid-state batteries are multifaceted. Key issues include sluggish ion transport within the electrolyte bulk, poor charge transfer at electrode-electrolyte interfaces, unstable solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation, and uncontrolled lithium dendrite growth. The following table summarizes dominant failure modes and their impact on battery performance:

| Failure Mode | Impact at Low Temperatures | Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Reduced Ionic Conductivity | Exponential drop in $\sigma$ due to limited ion mobility | Design electrolytes with low $E_a$; enhance amorphous phases |

| High Interfacial Impedance | Increased charge transfer resistance; poor electrode wetting | Engineer stable interfaces; use compliant interlayers |

| Unstable SEI/CEI Formation | Thick, resistive layers leading to capacity fade | Promote LiF-rich SEI; control electrolyte decomposition |

| Lithium Dendrite Growth | Short circuits via grain boundaries or cracks | Incorporate mechanical reinforcements; optimize pressure |

To address these challenges, researchers have developed advanced solid-state electrolytes with tailored properties. Inorganic solid-state electrolytes, such as oxides, sulfides, and halides, exhibit high intrinsic conductivity but suffer from interfacial issues. For instance, sulfide-based electrolytes like Li${10}$GeP$_2$S${12}$ (LGPS) achieve room-temperature conductivities of 12 mS/cm, retaining 0.4 mS/cm at -45 °C. Halide electrolytes (e.g., Li$_3$InCl$_6$) offer excellent compatibility with cathodes, with conductivities of 1.6 × 10$^{-4}$ S/cm at -10 °C. The ionic conductivity trends for various inorganic systems are compared below:

| Electrolyte Type | Representative Material | Ionic Conductivity at 25 °C (S/cm) | Ionic Conductivity at -20 °C (S/cm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxide | LLZO | 10$^{-4}$–10$^{-3}$ | 10$^{-6}$–10$^{-5}$ |

| Sulfide | LGPS | 10$^{-2}$ | 10$^{-4}$ |

| Halide | Li$_3$InCl$_6$ | 10$^{-3}$ | 10$^{-4}$ |

Polymer-based solid-state electrolytes, including solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) and gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs), provide flexibility and processability. Poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) is widely studied, but its conductivity plummets below 0 °C. Strategies like plasticization with succinonitrile (SN) or in situ polymerization of 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) have yielded conductivities of 0.22 mS/cm at -20 °C. The VTF equation parameters for optimized polymers are critical: lower $T_0$ values correlate with improved low-temperature performance. For example, cross-linked networks with SN reduce crystallinity, enabling conductivities of 0.19 mS/cm at 25 °C and sustained operation at 0 °C.

Composite solid-state electrolytes (CSEs) merge inorganic fillers with polymer matrices to synergize benefits. Incorporating LLZTO or LATP into PEO/PVDF-HFP matrices suppresses crystallization and creates continuous ion pathways. A representative CSE with 15 wt% LATP nanowires achieves 6.0 × 10$^{-4}$ S/cm at 25 °C and functions from -20 °C to 60 °C. The role of fillers extends beyond conductivity enhancement; they also mitigate space-charge effects. The dielectric constant $\epsilon_r$ of additives like BaTiO$_3$ influences ion dissociation: $$\epsilon_r = \frac{C}{\epsilon_0 A}$$ where $C$ is capacitance, $\epsilon_0$ is vacuum permittivity, and $A$ is area. Higher $\epsilon_r$ materials promote Li$^+$ dissociation, boosting conductivity.

Interfacial engineering is paramount for low-temperature solid-state batteries. Unstable interfaces lead to high impedance and rapid degradation. Coating cathodes with LiNbO$3$ or forming LiF-rich SEI layers via fluorinated additives reduces charge transfer barriers. The charge transfer resistance $R{ct}$ follows: $$R_{ct} = \frac{RT}{nF j_0}$$ where $n$ is electron number, $F$ is Faraday’s constant, and $j_0$ is exchange current density. Minimizing $R_{ct}$ through interface modifications allows stable cycling at -30 °C. In situ polymerization techniques further improve adhesion, creating conformal interfaces that withstand thermal stress.

Emerging materials like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) offer nanoporous channels for rapid ion transport. MOF-based electrolytes functionalized with sulfonate groups achieve Li$^+$ transference numbers of 0.92 and conductivities of 7.13 × 10$^{-4}$ S/cm at 30 °C, extending operation to -20 °C. The ionic conductivity in MOFs is described by: $$\sigma = n e \mu$$ where $n$ is carrier concentration, $e$ is electron charge, and $\mu$ is mobility. Tuning pore chemistry enhances $n$ and $\mu$, enabling all-solid-state batteries with wide temperature tolerance.

Future directions for low-temperature solid-state batteries encompass four domains: novel materials, advanced characterization, mechanistic insights, and standardized protocols. First, computational screening can identify electrolytes with low $E_a$ and high $\sigma$. High-entropy compositions and superconcentrated designs may overcome existing limits. Second, in situ techniques like cryo-electron microscopy and solid-state NMR will unravel interfacial dynamics. Third, multiscale modeling must elucidate ion transport across bulk and interfaces. Finally, industry standards for testing low-temperature performance will accelerate commercialization.

In conclusion, solid-state electrolytes are pivotal for realizing low-temperature lithium metal batteries. Through material innovation and interface control, solid-state batteries can achieve high energy density and safety across a broad temperature range. Continued research into ion transport mechanisms and failure mitigation will unlock the full potential of solid-state battery technology for applications in electric vehicles, aerospace, and grid storage.