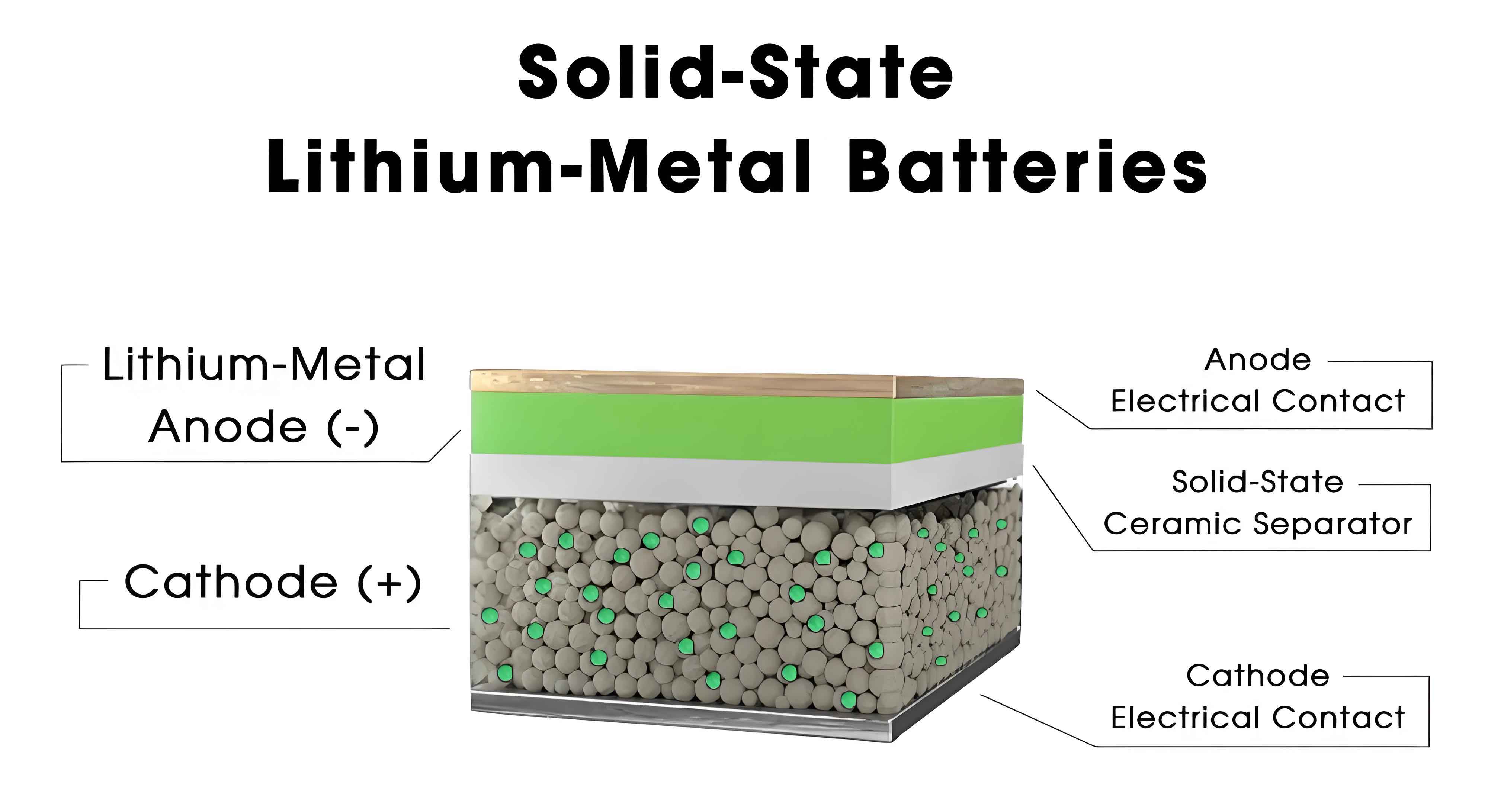

In recent decades, lithium-ion batteries have been extensively researched and applied, but the growing secondary battery market demands higher energy density and safety. Traditional liquid lithium-ion batteries pose risks of leakage and combustion, making non-flammable all-solid-state batteries a promising solution. Among mainstream solid electrolyte systems, sulfide solid electrolytes stand out due to their excellent processability and high ionic conductivity (10−3–10−2 S/cm). Sulfide electrolytes can be categorized into glassy, glass-ceramic, and crystalline types, with crystalline variants like Li10GeP2S12 and Li9.54Si1.74P1.44S11.7Cl0.3 achieving ionic conductivities comparable to liquid electrolytes. However, their poor electrochemical stability and high cost limit widespread use. Argyrodite-type sulfide solid electrolytes, such as Li6PS5X (X = Cl, Br, I), have gained attention for their balanced conductivity and stability. Early studies on Li6PS5X reported relatively low ionic conductivity, but computational work by de Klerk et al. demonstrated a positive correlation between anion disorder at the 4d site (S2−/Cl− mixing) and ionic conductivity. Increasing halogen substitution for sulfur enhances anion disorder and Li+ vacancy concentration, thereby boosting ionic conductivity. Adeli et al. experimentally confirmed that Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 exhibits the highest ionic conductivity in the x = 1.0–1.5 range for Li7−xPS6−xClx. While previous research has focused on improving ball milling and sintering processes or doping with elements like Si and O to enhance ionic conductivity or lithium stability, the impact of chlorine content on interfacial stability and performance in solid-state batteries remains underexplored. Electrolytes in solid-state batteries are used in various forms, such as mixtures with electrodes and as separate layers. Most studies evaluate overall battery performance using the same electrolyte material across components, which obscures the specific effects on cathode and electrolyte layer interfaces. Contradictory findings exist: some reports suggest that chlorine-rich Li5.5PS4.5Cl1.5 offers better stability in cathodes, while others indicate higher decomposition. Similarly, for electrolyte layers, high chlorine content may improve lithium stability but reduce cycling performance. Therefore, systematic research on tailoring chlorine content to optimize interfaces in different battery components is crucial for advancing solid-state battery technology.

In this study, we synthesized Li7−xPS6−xClx (x = 1.0–1.5) solid electrolytes via solid-state sintering and investigated the effects of chlorine content on their structural and electrochemical properties. We found that increasing x enhances ionic conductivity but reduces thermal and electrochemical stability, with Li5.7PS4.7Cl1.3 exhibiting the highest crystallinity and lowest activation energy. We assembled all-solid-state batteries with LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM) composite cathodes and evaluated their electrochemical performance. By analyzing the behavior of different electrolytes in composite cathodes and as electrolyte layers, combined with X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis, we systematically assessed how chlorine content influences interfacial stability and overall performance. Our results show that in composite cathodes, higher chlorine content degrades cycling stability, but Li5.7PS4.7Cl1.3 strikes a balance between ionic conduction and interfacial reactions, reducing initial cathode impedance and enhancing rate performance (99 mA·h/g at 3C). As an electrolyte layer, high-chlorine materials lead to rapid interfacial degradation at both electrodes, impairing cycle life. Using low-chlorine Li6PS5Cl mitigates interface deterioration, facilitating good contact and ion transport. By optimizing chlorine content, we achieved superior overall performance, with an NCM@Li5.7PS4.7Cl1.3|Li6PS5Cl|LiIn battery retaining 132.8 mA·h/g after 300 cycles at 0.5C and 20 mg/cm2 loading, demonstrating 78.4% capacity retention. This work provides guidance for designing high-performance all-solid-state batteries by controlling chlorine content to stabilize interfaces and enhance ion transport.

We prepared Li7−xPS6−xClx solid electrolytes using solid-state sintering. Raw materials, including lithium sulfide (Li2S, 99.9%), phosphorus pentasulfide (P2S5, 99%), and lithium chloride (LiCl, 99.99%), were weighed in stoichiometric ratios and ball-milled in zirconia jars at 400 rpm for 4 hours with a ball-to-powder ratio of 30:1. The mixtures were then sintered at 500°C for 8 hours under argon atmosphere to obtain the electrolytes, labeled as Cl 1.0 to Cl 1.5 based on x values, corresponding to chlorine mole fractions of 25% to 37.5%. For battery assembly, we used a dry process in an argon-filled glovebox. Composite cathodes were prepared by mixing NCM, Li7−xPS6−xClx, and vapor-grown carbon fiber (VGCF) in a 70:27:3 mass ratio, followed by grinding for 10 minutes. The cathodes were labeled NCM@Cl 1.0 to NCM@Cl 1.5 based on the electrolyte used. Batteries were assembled in a layered structure: 10–24 mg of composite cathode, 120 mg of Li7−xPS6−xClx electrolyte layer, and an indium foil, cold-pressed at 600 MPa for 3 minutes. A lithium foil (1.5 mg) was attached to the negative side before sealing in 2032 coin cells. For cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests, we prepared VGCF@Li7−xPS6−xClx by mixing electrolyte and VGCF in a 9:1 mass ratio, followed by homogenization and pressing with electrolyte and indium foil. LiIn symmetric cells were made by sandwiching 120 mg electrolyte between two indium foils and adding lithium foils. Structural characterization involved X-ray diffraction (XRD) using a Rigaku MiniFlex600 diffractometer (10°–80° range, 5°/min scan rate) and Raman spectroscopy (Horiba JobinYvon LabRAM HR800, 100–800 cm−1 range, 532 nm laser). Chemical states were analyzed via XPS (ULVAC-PHI VersaProbe 4), and morphology was examined using FIB-SEM (ZEISS Crossbeam 540). All samples were handled in the glovebox and transferred under vacuum to prevent air exposure. Electrochemical tests included impedance spectroscopy (Gamry 600+, 5 MHz–0.1 Hz range, 10 mV bias for electrolytes, 30 mV for cells), DC polarization (1 V applied potential), CV (2.6–4.6 V vs. Li/Li+, 0.1 mV/s), and galvanostatic cycling (LAND CT-2001A, 0.1C formation, 0.3C second cycle, 0.5C cycling, 1C = 170 mA/g). DRT analysis was performed using DRTtools in MATLAB to deconvolute impedance spectra and identify relaxation times associated with different interfaces.

The XRD patterns of Li7−xPS6−xClx electrolytes (x = 1.0–1.5) matched the standard Li6PS5Cl structure (PDF#97-041-8490), confirming phase purity. As x increased, peaks shifted to higher angles due to Cl− substitution for S2−, reducing lattice parameters. Crystallinity improved from x = 1.0 to 1.3, as indicated by sharper peaks and decreased full width at half maximum (FWHM from 0.139 Å to 0.098 Å), but degraded at x = 1.4–1.5 (FWHM increased to 0.215 Å). Raman spectra showed a red shift in the PS43− peak at ~423 cm−1 with higher chlorine content, signifying lattice softening and weakened Li+ binding, which facilitates ion transport but may compromise stability. The intensity of this peak followed a similar trend, highest for x = 1.3, aligning with XRD results. These findings suggest that optimal sintering at 500°C yields high crystallinity for moderate chlorine content, but excessive chlorine reduces thermal stability, consistent with literature reports that higher x narrows the phase-pure temperature window. Ionic conductivity measurements revealed a monotonic increase with x, from ~3.2 mS/cm for Cl 1.0 to 9.5 mS/cm for Cl 1.5, attributed to enhanced anion disorder and Li+ vacancy concentration. Electronic conductivity, determined by DC polarization, remained below 1 × 10−9 mS/cm for all samples, with a slight increase then decrease as x rose. Arrhenius plots from variable-temperature impedance tests yielded activation energies (Ea) that decreased from 0.36 eV for Cl 1.0 to 0.314 eV for Cl 1.3, then increased to 0.33 eV for Cl 1.5. The lower Ea for Cl 1.3 reflects its high crystallinity and defined ion transport pathways, despite Cl 1.5 having the highest conductivity. CV tests on VGCF@Li7−xPS6−xClx|Li7−xPS6−xClx|LiIn cells showed oxidation onset at 2.6 V vs. Li/Li+, indicating continuous decomposition during charging in NCM-based solid-state batteries. Peak currents and areas increased with chlorine content, suggesting greater decomposition extent due to reduced thermodynamic stability. Irreversible oxidation was observed over cycles, with minimal reduction currents, confirming persistent electrolyte degradation in practical applications.

We evaluated the performance of all-solid-state batteries with composite cathodes containing different Li7−xPS6−xClx electrolytes. Batteries used the same electrolyte layer (Cl 1.0) to isolate cathode effects. Initial discharge capacities at 0.1C improved with higher chlorine content, from 163.1 mA·h/g for NCM@Cl 1.0 to 178.5 mA·h/g for NCM@Cl 1.3, due to enhanced ionic conductivity facilitating better active material utilization. However, initial Coulombic efficiency peaked at 81.8% for NCM@Cl 1.3 and dropped to 80.5% for NCM@Cl 1.5, as excessive decomposition contributed to charging capacity but not discharge. At 0.5C, discharge capacities followed a similar trend, with NCM@Cl 1.3 achieving the highest value. Rate performance tests (0.1C to 3C) demonstrated that NCM@Cl 1.3 excelled, delivering 121 mA·h/g at 2C and 99 mA·h/g at 3C, a 30% improvement over NCM@Cl 1.0. Under high loading (20 mg/cm2), NCM@Cl 1.3 exhibited the lowest polarization voltage, whereas NCM@Cl 1.5 showed higher polarization despite its superior intrinsic conductivity. Cycling stability at 0.5C revealed capacity retention orders: NCM@Cl 1.0 (90% after 100 cycles) > NCM@Cl 1.3 (87%) > NCM@Cl 1.5 (82%), indicating that higher chlorine content degrades cycle life. Post-cycling analysis via XPS showed increased proportions of decomposition products like polysulfides and phosphorus-sulfur compounds for higher x values, confirming greater electrolyte oxidation. FIB-SEM images of cycled cathodes revealed more pores and particle fractures in NCM@Cl 1.0, denser structures in NCM@Cl 1.3, and severe decomposition with irregular particles in NCM@Cl 1.5. DRT analysis of impedance spectra identified key relaxation times: ~10−7–10−6 s for grain boundaries, 3×10−5–5×10−5 s for SEI at the anode, ~10−4 s for cathode electrolyte interphase (CEI), and >10−1 s for charge transfer and diffusion. For NCM@Cl 1.3, CEI and charge transfer resistances decreased after cycling, likely due to decomposition products filling voids and improving contact, whereas they increased for NCM@Cl 1.0 and NCM@Cl 1.5. This balance between ionic conduction and interfacial reactions explains the superior rate and cycling performance of NCM@Cl 1.3.

When Li7−xPS6−xClx electrolytes were used as standalone layers with the same NCM@Cl 1.3 cathode, performance varied significantly. Initial discharge capacities and Coulombic efficiencies peaked for Cl 1.3 layers but cycling stability was best for Cl 1.0. Specifically, Cl 1.0 layers achieved 179 mA·h/g at 0.5C with 88.4% retention after 100 cycles, outperforming Cl 1.3 layers which suffered from rapid impedance growth. DRT analysis showed that cells with Cl 1.3 electrolyte layers had higher SEI and CEI resistances post-cycling, attributed to increased decomposition at electrode interfaces. SEM of cycled interfaces revealed more surface particles and decomposition products for higher chlorine content, directly impeding ion transport. In contrast, Cl 1.0 layers maintained stable interfaces with fewer side reactions. The discrepancy between cathode and electrolyte layer behavior underscores the importance of application context: in composite cathodes, electrolyte decomposition can enhance particle contact, but in electrolyte layers, it primarily degrades interfacial integrity. Crystallinity also plays a role; highly crystalline Cl 1.3 is more susceptible to mechanical strain and interfacial failure as a layer. Thus, for electrolyte layers, lower chlorine content like Cl 1.0 offers better stability, whereas for cathodes, moderate chlorine (Cl 1.3) optimizes ion transport and interfacial balance.

To quantify the electrochemical properties, we present key data in tables and formulas. The ionic conductivity (σ) follows the Arrhenius equation: $$ \sigma = \sigma_0 \exp\left(-\frac{E_a}{kT}\right) $$ where Ea is activation energy, k is Boltzmann’s constant, and T is temperature. The electronic conductivity (σe) was calculated from DC polarization currents using Ohm’s law. The table below summarizes the properties of Li7−xPS6−xClx electrolytes:

| Chlorine Content (x) | Ionic Conductivity (mS/cm) | Electronic Conductivity (mS/cm) | Activation Energy (eV) | Crystallinity (FWHM, Å) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.0 | 3.2 | 2.1 × 10−10 | 0.36 | 0.139 |

| 1.1 | 4.5 | 3.5 × 10−10 | 0.34 | 0.125 |

| 1.2 | 6.1 | 4.8 × 10−10 | 0.32 | 0.110 |

| 1.3 | 7.8 | 5.2 × 10−10 | 0.314 | 0.098 |

| 1.4 | 8.7 | 4.1 × 10−10 | 0.325 | 0.180 |

| 1.5 | 9.5 | 3.0 × 10−10 | 0.33 | 0.215 |

For battery performance, the optimized NCM@Cl 1.3|Cl 1.0|LiIn cell achieved outstanding results, as shown in the cycling data below:

| Cycle Number | Discharge Capacity (mA·h/g) | Capacity Retention (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 200.9 | 100 |

| 50 | 175.3 | 87.2 |

| 100 | 168.5 | 83.9 |

| 200 | 152.1 | 75.7 |

| 300 | 132.8 | 78.4 |

The DRT analysis allowed us to model the impedance using a distribution function: $$ Z(\omega) = R_\infty + \int_0^\infty \frac{g(\tau)}{1 + j\omega\tau} d\tau $$ where g(τ) is the relaxation time distribution, and ω is angular frequency. The identified time constants correspond to specific processes: grain boundaries (τ ~ 10−6 s), SEI/CEI (τ ~ 10−5–10−3 s), and charge transfer (τ ~ 10−2–10 s). For NCM@Cl 1.3 cathodes, the decrease in charge transfer resistance over cycles can be described by an empirical equation: $$ R_{ct}(t) = R_0 \exp(-kt) $$ where R0 is initial resistance and k is a constant related to interface stabilization.

In conclusion, we systematically optimized chlorine content in Li7−xPS6−xClx solid electrolytes for all-solid-state batteries. Increasing x enhances ionic conductivity but reduces stability, with Li5.7PS4.7Cl1.3 offering the best balance for composite cathodes due to high crystallinity and low activation energy. As an electrolyte layer, lower chlorine content (e.g., Cl 1.0) minimizes interfacial degradation. By tailoring chlorine distribution—using Cl 1.3 in cathodes and Cl 1.0 in electrolyte layers—we achieved high-performance solid-state batteries with excellent rate capability and long cycle life. This strategy highlights the importance of component-specific electrolyte design for advancing solid-state battery technology, paving the way for safer and more energy-dense energy storage systems. Future work could explore dynamic interface engineering and multi-element doping to further enhance stability in all-solid-state batteries.